Peter Sjöstedt-H in iai:

“[W]hat we experience in our dreams … is as much a part of the overall economy of our soul as anything we ‘really’ experience.”

“[W]hat we experience in our dreams … is as much a part of the overall economy of our soul as anything we ‘really’ experience.”

– Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

Such is it with dreams; even more so with psychedelics. But psychedelic experience not only enriches the self, it can contribute to our understanding of what the self is or can be. Psychedelic intake can violently alter aspects of the prosaic, or ordinary self; moreover it can add multiple further facets. In fact, it can in extremis destroy or multiply the “self” – with a range from individuality through unity to infinity, as we shall see.

First let us look at what can be meant by this ambiguous term, “the self”, in its ordinary sense. The self can be understood in its relation to matter, and in its relation to mind. In relation to matter, the self can be understood as, i. reducible to part of the body (materialism), ii. a soul distinct from the material body (dualism), iii. a mind that creates what appears as matter (idealism), and iv. the self can be understood as being at one with an extended body (processism). The common view is undoubtedly i. and ii., the biological and the predominantly religious – though both are fundamentally faith positions. As anthropologist, cyberneticist Gregory Bateson lamented:

“These two species of superstition … the supernatural and the mechanical, feed each other. In our day, the premise of external mind seems to invite charlatanism, promoting in turn a retreat back into a materialism which then becomes intolerably narrow.”

Whatever the mind-matter view, all will still understand by “self” its phenomenal aspects as well – the self in relation to mind. Certain thinkers, following Hume’s suggestion, consider the “self” to be an illusion of the mind in the sense that the word does not refer to any particular thing underlying the bundle of types of experience listed below. Such a belief claims that we cannot directly perceive the “self” as such, but only phenomena such as colour, sound, emotion, etc. Kant in response argues that though we cannot directly perceive the pure, underlying self, we must nonetheless assume it to exist (as “pure apperception”) as that which holds all such experiences together as one – a bundle is a unity that, as such, must be tied.

More here.

Two thoughts have long come unbidden to my mind whenever I hear people talking about doing their family trees, or, more recently, getting their DNA done. The first is of Bruce Willis’s character in Pulp Fiction, the boxer Butch Coolidge in the back of the taxi, who, when asked by his South American driver what his name means, replies, “I’m an American, baby, our names don’t mean shit.” The other is of Seneca, who wrote in his Moral Letters to Lucilius: “If there is any good in philosophy, it is this, — that it never looks into pedigrees. All men, if traced back to their original source, spring from the gods.”

Two thoughts have long come unbidden to my mind whenever I hear people talking about doing their family trees, or, more recently, getting their DNA done. The first is of Bruce Willis’s character in Pulp Fiction, the boxer Butch Coolidge in the back of the taxi, who, when asked by his South American driver what his name means, replies, “I’m an American, baby, our names don’t mean shit.” The other is of Seneca, who wrote in his Moral Letters to Lucilius: “If there is any good in philosophy, it is this, — that it never looks into pedigrees. All men, if traced back to their original source, spring from the gods.”

In the dark days of quarantine, I have a habit, born of a fretful insomnia, of rising before dawn. Descending the stairs from my attic room, passing second-floor bedrooms, I imagine I am an all-knowing god of some small universe, like Leo Tolstoy in War and Peace, and can peer into the dreams of my loved ones.

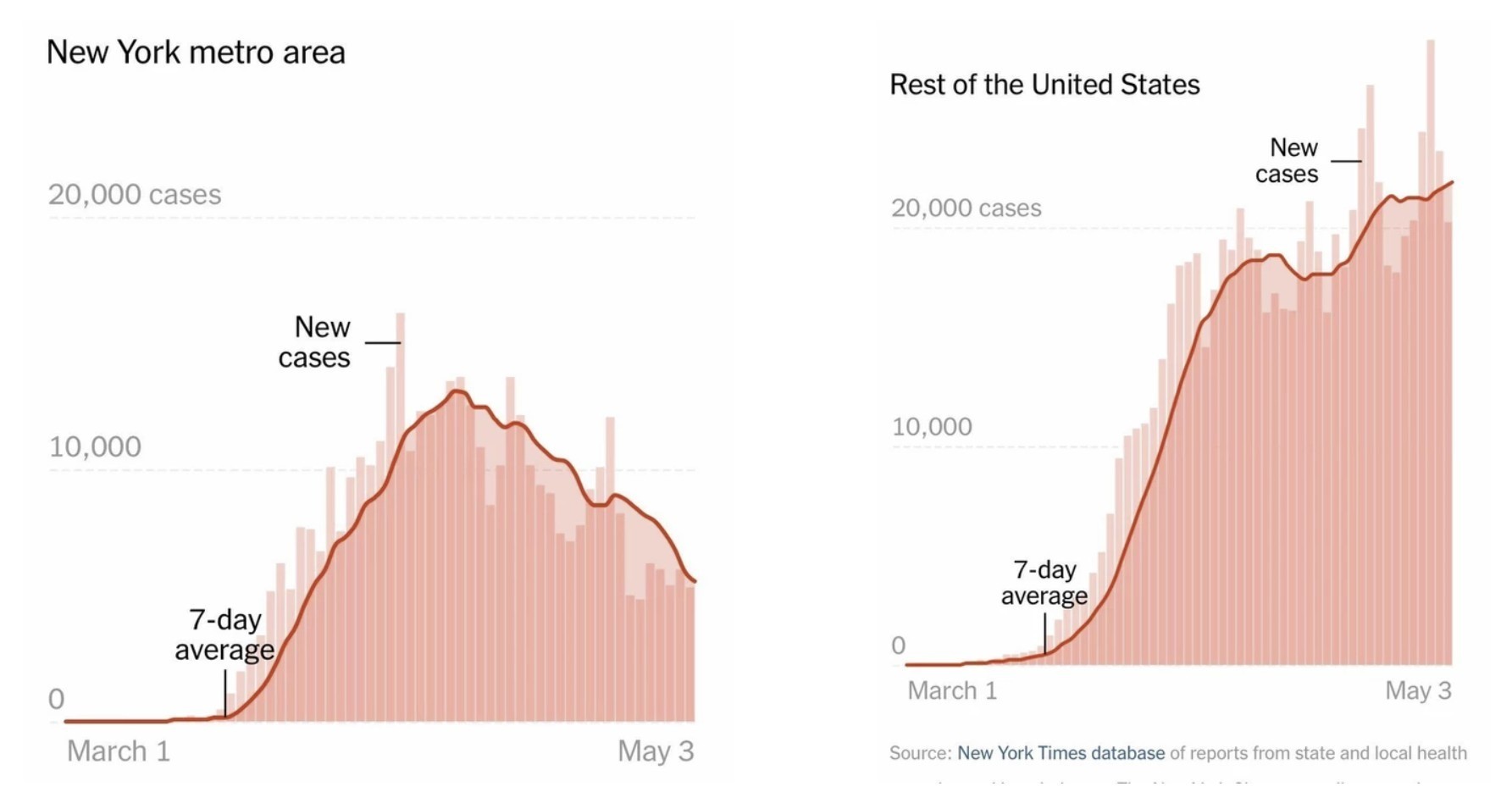

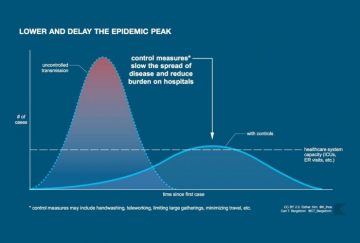

In the dark days of quarantine, I have a habit, born of a fretful insomnia, of rising before dawn. Descending the stairs from my attic room, passing second-floor bedrooms, I imagine I am an all-knowing god of some small universe, like Leo Tolstoy in War and Peace, and can peer into the dreams of my loved ones. Twenty years ago, the US Department of Defense set out a clear warning: “Historians in the next millennium may find that the 20th century’s greatest fallacy was the belief that infectious diseases were nearing elimination. The resultant complacency has actually increased the threat.” Along with other western nations, federal and state governments in America had spent the previous decade or so dismantling public health programmes dealing with communicable diseases in order to concentrate funds on degenerative illnesses: diabetes, heart disease, cancer, stroke. Corporate investment in the development of new vaccines and antibiotics almost dried up, as if the battle that humans had waged over millennia against plague and pestilence had now been won – at least in the developed world. Michael Osterholm, the Minnesota state epidemiologist, informed US Congress in 1996: “I am here to bring you the sobering and unfortunate news that our ability to detect and monitor infectious disease threats to health in this country is in serious jeopardy. . . . For 12 of the states or territories, there is no one who is responsible for food or water-borne disease surveillance. You could sink the Titanic in their back yard and they would not know they had water.”

Twenty years ago, the US Department of Defense set out a clear warning: “Historians in the next millennium may find that the 20th century’s greatest fallacy was the belief that infectious diseases were nearing elimination. The resultant complacency has actually increased the threat.” Along with other western nations, federal and state governments in America had spent the previous decade or so dismantling public health programmes dealing with communicable diseases in order to concentrate funds on degenerative illnesses: diabetes, heart disease, cancer, stroke. Corporate investment in the development of new vaccines and antibiotics almost dried up, as if the battle that humans had waged over millennia against plague and pestilence had now been won – at least in the developed world. Michael Osterholm, the Minnesota state epidemiologist, informed US Congress in 1996: “I am here to bring you the sobering and unfortunate news that our ability to detect and monitor infectious disease threats to health in this country is in serious jeopardy. . . . For 12 of the states or territories, there is no one who is responsible for food or water-borne disease surveillance. You could sink the Titanic in their back yard and they would not know they had water.” In this half-life of quarantine, danger lurks in the unlikeliest of places: the touch of an elevator button, a store-bought carton of milk, my son’s sneeze. Insidious and cunning, death is everywhere around us.

In this half-life of quarantine, danger lurks in the unlikeliest of places: the touch of an elevator button, a store-bought carton of milk, my son’s sneeze. Insidious and cunning, death is everywhere around us. Stuart Jeffries in The Guardian:

Stuart Jeffries in The Guardian: Tyler Cowen interviews Adam Tooze over at Medium:

Tyler Cowen interviews Adam Tooze over at Medium:

Jonathan Fuller in Boston Review:

Jonathan Fuller in Boston Review: George Scialabba reviews Martha Nussbaum’s The Cosmopolitan Tradition: A Noble but Flawed Ideal in Inference:

George Scialabba reviews Martha Nussbaum’s The Cosmopolitan Tradition: A Noble but Flawed Ideal in Inference: “[W]hat we experience in our dreams … is as much a part of the overall economy of our soul as anything we ‘really’ experience.”

“[W]hat we experience in our dreams … is as much a part of the overall economy of our soul as anything we ‘really’ experience.” “The country Trump promised to make great again has never in its history seemed so pitiful,”

“The country Trump promised to make great again has never in its history seemed so pitiful,”  “I spoke for you,” the qawwal said.

“I spoke for you,” the qawwal said. The skull in Vanitas Still Life, while undoubtedly grim, bears a wry, gapped grin—a grin missing four front teeth. Stripped of its flesh, our bone structure apparently discloses a faint, effortless smile. The skull’s stark, denuded presence signals gravity, but its blithe affect signals buoyancy. Perhaps this face of death reflects both the weeping Heraclitus and the laughing Democritus, pointing viewers back to Ecclesiastes: there is “a time to weep and a time to laugh.” Wisdom here comes lodged in apposition—pairs of apparent opposites, united by the word and: “a time to be born, and a time to die … a time to break down, and a time to build up … a time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together.” These lines in Ecclesiastes encourage readers to imagine a world in which the poles of existence create vibrant tension, in which life and death, gathering and releasing, embracing and refraining, weeping and laughing, do not negate each other but instead balance and enrich. There is aggregation and integration—even with loss, even in death.

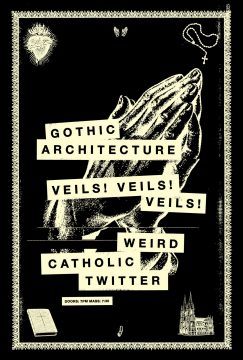

The skull in Vanitas Still Life, while undoubtedly grim, bears a wry, gapped grin—a grin missing four front teeth. Stripped of its flesh, our bone structure apparently discloses a faint, effortless smile. The skull’s stark, denuded presence signals gravity, but its blithe affect signals buoyancy. Perhaps this face of death reflects both the weeping Heraclitus and the laughing Democritus, pointing viewers back to Ecclesiastes: there is “a time to weep and a time to laugh.” Wisdom here comes lodged in apposition—pairs of apparent opposites, united by the word and: “a time to be born, and a time to die … a time to break down, and a time to build up … a time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together.” These lines in Ecclesiastes encourage readers to imagine a world in which the poles of existence create vibrant tension, in which life and death, gathering and releasing, embracing and refraining, weeping and laughing, do not negate each other but instead balance and enrich. There is aggregation and integration—even with loss, even in death. More and more young Christians, disillusioned by the political binaries, economic uncertainties and spiritual emptiness that have come to define modern America, are finding solace in a decidedly anti-modern vision of faith. As the coronavirus and the subsequent lockdowns throw the failures of the current social order into stark relief, old forms of religiosity offer a glimpse of the transcendent beyond the present.

More and more young Christians, disillusioned by the political binaries, economic uncertainties and spiritual emptiness that have come to define modern America, are finding solace in a decidedly anti-modern vision of faith. As the coronavirus and the subsequent lockdowns throw the failures of the current social order into stark relief, old forms of religiosity offer a glimpse of the transcendent beyond the present. In the spring of 1822 an employee in one of the world’s first offices – that of the East India Company in London – sat down to write a letter to a friend. If the man was excited to be working in a building that was revolutionary, or thrilled to be part of a novel institution which would transform the world in the centuries that followed, he showed little sign of it. “You don’t know how wearisome it is”, wrote Charles Lamb, “to breathe the air of four pent walls, without relief, day after day, all the golden hours of the day between ten and four.” His letter grew ever-less enthusiastic, as he wished for “a few years between the grave and the desk”. No matter, he concluded, “they are the same.” The world that Lamb wrote from is now long gone. The infamous East India Company collapsed in ignominy in the 1850s. Its most famous legacy, British colonial rule in India, disintegrated a century later. But his letter resonates today, because, while other empires have fallen, the empire of the office has triumphed over modern professional life. The dimensions of this empire are awesome. Its population runs into hundreds of millions, drawn from every nation on Earth. It dominates the skylines of our cities – their tallest buildings are no longer cathedrals or temples but multi-storey vats filled with workers. It delineates much of our lives. If you are a hardworking citizen of this empire you will spend more waking hours with the irritating colleague to your left whose spare shoes invade your footwell than with your husband or wife, lover or children.

In the spring of 1822 an employee in one of the world’s first offices – that of the East India Company in London – sat down to write a letter to a friend. If the man was excited to be working in a building that was revolutionary, or thrilled to be part of a novel institution which would transform the world in the centuries that followed, he showed little sign of it. “You don’t know how wearisome it is”, wrote Charles Lamb, “to breathe the air of four pent walls, without relief, day after day, all the golden hours of the day between ten and four.” His letter grew ever-less enthusiastic, as he wished for “a few years between the grave and the desk”. No matter, he concluded, “they are the same.” The world that Lamb wrote from is now long gone. The infamous East India Company collapsed in ignominy in the 1850s. Its most famous legacy, British colonial rule in India, disintegrated a century later. But his letter resonates today, because, while other empires have fallen, the empire of the office has triumphed over modern professional life. The dimensions of this empire are awesome. Its population runs into hundreds of millions, drawn from every nation on Earth. It dominates the skylines of our cities – their tallest buildings are no longer cathedrals or temples but multi-storey vats filled with workers. It delineates much of our lives. If you are a hardworking citizen of this empire you will spend more waking hours with the irritating colleague to your left whose spare shoes invade your footwell than with your husband or wife, lover or children.