Anthony King in The Scientist:

One of the oldest vaccines could protect us against our newest infectious disease, COVID-19. The vaccine has been given to babies to protect them against tuberculosis for almost a century, but has been shown to shield them from other infections too, prompting scientists to investigate whether it can protect against the coronavirus. This Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine, named after two French microbiologists, consists of a live weakened strain of Mycobacterium bovis, a cousin of M. tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes tuberculosis. BCG has been given to more than 4 billion individuals, making it the most widely administered vaccine globally. Because BCG protects babies against some viral infections in addition to TB, researchers decided to compare data from countries with and without mandatory BCG vaccination to see if immunization policies are linked to the number or severity of COVID-19 infections. A handful of preprint publications in the last two months noted that countries with an ongoing BCG vaccination program are experiencing lower death rates from COVID-19 than those without.

One of the oldest vaccines could protect us against our newest infectious disease, COVID-19. The vaccine has been given to babies to protect them against tuberculosis for almost a century, but has been shown to shield them from other infections too, prompting scientists to investigate whether it can protect against the coronavirus. This Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine, named after two French microbiologists, consists of a live weakened strain of Mycobacterium bovis, a cousin of M. tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes tuberculosis. BCG has been given to more than 4 billion individuals, making it the most widely administered vaccine globally. Because BCG protects babies against some viral infections in addition to TB, researchers decided to compare data from countries with and without mandatory BCG vaccination to see if immunization policies are linked to the number or severity of COVID-19 infections. A handful of preprint publications in the last two months noted that countries with an ongoing BCG vaccination program are experiencing lower death rates from COVID-19 than those without.

One study, for instance, found that mandatory BCG was associated with a significantly slower climb in both confirmed cases and deaths during the first 30-day period of an outbreak. Another modeled mortality in two dozen countries and reported that those without universal BCG vaccination, such as Italy, the US, and the Netherlands, were more severely affected by the pandemic than those with universal vaccination.

More here.

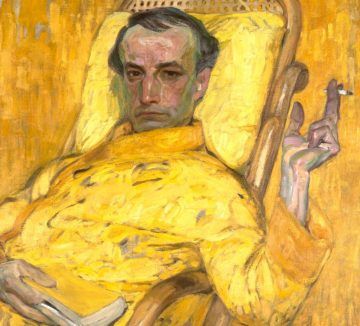

I’m not ashamed to say that I bought Joris-Karl Huysmans’s Against Nature because of the cover: Frantisek Kupka’s The Yellow Scale (Self-Portrait) from 1907 is an exhilarating study of the color yellow. Its human subject, slouched in a wicker armchair, a cigarette dangling from one hand while a single, louche finger marks the page of a book, could be the perfect image of Des Esseintes, the dissolute antihero of Huysmans’s novel. Strictly speaking, the painting is a self-portrait of the habitually mustached Kupka, but it bears more than a passing resemblance to Charles Baudelaire, who haunts almost every page of Against Nature. This novel, about a dyspeptic aesthete who “took pleasure in a life of studious decrepitude,” spends some two hundred pages luxuriating in excess and opulence while the hero cuts himself off from the rest of society.

I’m not ashamed to say that I bought Joris-Karl Huysmans’s Against Nature because of the cover: Frantisek Kupka’s The Yellow Scale (Self-Portrait) from 1907 is an exhilarating study of the color yellow. Its human subject, slouched in a wicker armchair, a cigarette dangling from one hand while a single, louche finger marks the page of a book, could be the perfect image of Des Esseintes, the dissolute antihero of Huysmans’s novel. Strictly speaking, the painting is a self-portrait of the habitually mustached Kupka, but it bears more than a passing resemblance to Charles Baudelaire, who haunts almost every page of Against Nature. This novel, about a dyspeptic aesthete who “took pleasure in a life of studious decrepitude,” spends some two hundred pages luxuriating in excess and opulence while the hero cuts himself off from the rest of society. Stephen Wolfram blames himself for not changing the face of physics sooner.

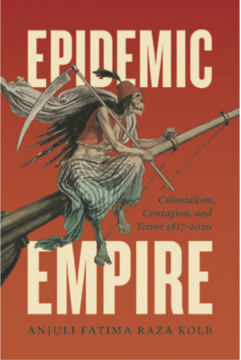

Stephen Wolfram blames himself for not changing the face of physics sooner. As the coronavirus began to take hold of our lives, our news, and became our undeniable, global, shared reality, I kept thinking about Anjuli Raza Kolb’s upcoming book,

As the coronavirus began to take hold of our lives, our news, and became our undeniable, global, shared reality, I kept thinking about Anjuli Raza Kolb’s upcoming book,  The book is Bernadette Mayer’s Midwinter Day. Mayer wrote it, the whole thing, every word, on December 22, 1978. Before today, I’d read only parts, but this is a book to be swallowed whole, hour by hour, the way Mayer wrote it. Therefore, I’m currently parked in a chair in the Lebanon, New Hampshire, public library, attempting a small degree of penance through reading.

The book is Bernadette Mayer’s Midwinter Day. Mayer wrote it, the whole thing, every word, on December 22, 1978. Before today, I’d read only parts, but this is a book to be swallowed whole, hour by hour, the way Mayer wrote it. Therefore, I’m currently parked in a chair in the Lebanon, New Hampshire, public library, attempting a small degree of penance through reading. I can’t think of another song that better approximates the soft, giddy feeling of something new suddenly opening up. The song’s first few movements—the album version is almost twenty-three minutes, in total—make me feel as if I have just crested a long hill. Kraftwerk wrote often about motion—the band was interested in ideas of repetition, inertia, speed—which might be part of why its records feel so transporting. To anyone who feels a desire to briefly depart Earth, I say cue up “

I can’t think of another song that better approximates the soft, giddy feeling of something new suddenly opening up. The song’s first few movements—the album version is almost twenty-three minutes, in total—make me feel as if I have just crested a long hill. Kraftwerk wrote often about motion—the band was interested in ideas of repetition, inertia, speed—which might be part of why its records feel so transporting. To anyone who feels a desire to briefly depart Earth, I say cue up “ Rashid Khalidi’s account of Jewish settlers’ conquest of Palestine is informed and passionate. It pulls no punches in its critique of Jewish-Israeli policies (policies that have had wholehearted US support after 1967), but it also lays out the failings of the Palestinian leadership. Khalidi participated in this history as an activist scion of a leading Palestinian family: in Beirut during the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and as part of the Palestinian negotiating team prior to the 1995 Israeli-Palestinian peace accords. He slams Israel but his is also an elegy for the Palestinians, for their dispossession, for their failure to resist conquest. It is a relentless story of Jewish-Israeli bad faith, alongside one of Palestinian corruption and political short-sightedness.

Rashid Khalidi’s account of Jewish settlers’ conquest of Palestine is informed and passionate. It pulls no punches in its critique of Jewish-Israeli policies (policies that have had wholehearted US support after 1967), but it also lays out the failings of the Palestinian leadership. Khalidi participated in this history as an activist scion of a leading Palestinian family: in Beirut during the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and as part of the Palestinian negotiating team prior to the 1995 Israeli-Palestinian peace accords. He slams Israel but his is also an elegy for the Palestinians, for their dispossession, for their failure to resist conquest. It is a relentless story of Jewish-Israeli bad faith, alongside one of Palestinian corruption and political short-sightedness. There’s an old belief that truth will always overcome error. Alas, history tells us something different. Without someone to fight for it, to put error on the defensive, truth may languish. It may even be lost, at least for some time. No one understood this better than the renowned Italian scientist Galileo Galilei. It is easy to imagine the man who for a while almost single-handedly founded the methods and practices of modern science as some sort of Renaissance ivory-tower intellectual, uninterested and unwilling to sully himself by getting down into the trenches in defense of science. But Galileo was not only a relentless advocate for what science could teach the rest of us. He was a master in outreach and a brilliant pioneer in the art of getting his message across. Today it may be hard to believe that science needs to be defended. But a political storm that denies the facts of science has swept across the land. This denialism ranges from the initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic to the reality of climate change. It’s heard in the preposterous arguments against vaccinating children and Darwin’s theory of evolution by means of natural selection. The scientists putting their careers, reputations, and even their health on the line to educate the public can take heart from Galileo, whose courageous resistance led the way.

There’s an old belief that truth will always overcome error. Alas, history tells us something different. Without someone to fight for it, to put error on the defensive, truth may languish. It may even be lost, at least for some time. No one understood this better than the renowned Italian scientist Galileo Galilei. It is easy to imagine the man who for a while almost single-handedly founded the methods and practices of modern science as some sort of Renaissance ivory-tower intellectual, uninterested and unwilling to sully himself by getting down into the trenches in defense of science. But Galileo was not only a relentless advocate for what science could teach the rest of us. He was a master in outreach and a brilliant pioneer in the art of getting his message across. Today it may be hard to believe that science needs to be defended. But a political storm that denies the facts of science has swept across the land. This denialism ranges from the initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic to the reality of climate change. It’s heard in the preposterous arguments against vaccinating children and Darwin’s theory of evolution by means of natural selection. The scientists putting their careers, reputations, and even their health on the line to educate the public can take heart from Galileo, whose courageous resistance led the way. Seventeen years after his death, Edward Said remains a powerful intellectual presence in academic and public discourse, a fact attested to by the appearance of two important new books. After Said, edited by Bashir Abu-Manneh, offers assessments of Said’s vast body of scholarship by a dozen noted writers and academics. The Selected Works of Edward Said, 1966–2006, edited by Moustafa Bayoumi and Andrew Rubin, two former students, is an expanded version of The Edward Said Reader, which was published a few years before his death in 2003. The Reader offered us a full picture of Said’s breadth and influence as a public intellectual; the new collection is more than 150 pages longer and includes eight essays that didn’t appear in the earlier volume, plus a new preface and an expanded introduction. The newly included essays range from overtly political sallies to reflective meditations on the “late style” in music and literature that were published posthumously. Some of them, like “Freud and the Non-European,” reflect concerns that preoccupied him toward the end of his life and are among the most complex and subtle of his writings. Others remind us how widely read he was, how broad his interests were, and how penetrating his insights could be. Coupled with the reflections on his major works in After Said, they also give the reader a sense of the consistency of his politics, imbued with a universalist and cosmopolitan humanism that sat at the center of his literary and political writings.

Seventeen years after his death, Edward Said remains a powerful intellectual presence in academic and public discourse, a fact attested to by the appearance of two important new books. After Said, edited by Bashir Abu-Manneh, offers assessments of Said’s vast body of scholarship by a dozen noted writers and academics. The Selected Works of Edward Said, 1966–2006, edited by Moustafa Bayoumi and Andrew Rubin, two former students, is an expanded version of The Edward Said Reader, which was published a few years before his death in 2003. The Reader offered us a full picture of Said’s breadth and influence as a public intellectual; the new collection is more than 150 pages longer and includes eight essays that didn’t appear in the earlier volume, plus a new preface and an expanded introduction. The newly included essays range from overtly political sallies to reflective meditations on the “late style” in music and literature that were published posthumously. Some of them, like “Freud and the Non-European,” reflect concerns that preoccupied him toward the end of his life and are among the most complex and subtle of his writings. Others remind us how widely read he was, how broad his interests were, and how penetrating his insights could be. Coupled with the reflections on his major works in After Said, they also give the reader a sense of the consistency of his politics, imbued with a universalist and cosmopolitan humanism that sat at the center of his literary and political writings. Upton Sinclair published

Upton Sinclair published  “Unlike Lenin, Hitler came to power in a free election, which makes Auschwitz also the result of free elections.” The East German dramatist and poet Heiner Müller wrote these words in late November of 1989, on the eve of the first free elections on the territory of the German Democratic Republic (socialist East Germany) since 1932, when the Nazis came to power. Never one for feel-good moments, Müller’s thinking was deeply out of sync with the general euphoria that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall. While giving a speech on Berlin’s Alexanderplatz on November 4, 1989, he didn’t echo the sweeping optimism of the other speakers but read a statement calling for independent unions; many in the crowd booed him. In his autobiography, Müller admitted that the fall of the GDR had not been easy for him: “Suddenly there was no adversary…whoever no longer has an enemy will meet him in the mirror.”

“Unlike Lenin, Hitler came to power in a free election, which makes Auschwitz also the result of free elections.” The East German dramatist and poet Heiner Müller wrote these words in late November of 1989, on the eve of the first free elections on the territory of the German Democratic Republic (socialist East Germany) since 1932, when the Nazis came to power. Never one for feel-good moments, Müller’s thinking was deeply out of sync with the general euphoria that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall. While giving a speech on Berlin’s Alexanderplatz on November 4, 1989, he didn’t echo the sweeping optimism of the other speakers but read a statement calling for independent unions; many in the crowd booed him. In his autobiography, Müller admitted that the fall of the GDR had not been easy for him: “Suddenly there was no adversary…whoever no longer has an enemy will meet him in the mirror.” This point goes to the heart of Zabala’s book, as well as to the mistaken concerns about the hermeneutic tradition he defends. To say, with Zabala, that “there is no ‘neutral observation language’ that can erase human differences,” and that “these differences are not the source of our problems but rather the only possible route to their provisional solution,” is not to embrace or give succor to those making power grabs using bald assertions of “alternative facts,” but the very opposite. It is to say that “facts, information, and data by themselves do nothing. ‘Facts remain robust,’ as [philosopher of science Bruno] Latour says, ‘only when they are supported by a common culture, by institutions that can be trusted, by a more or less decent public life, by more or less reliable media.’” Let’s be quick to douse the realist canard that is sure to arise at this point — that relativist arguments are self-negating since, if all statements of fact are subject to cultural, historical, and institutional contexts, then so is this one — by stating the obvious: of course Zabala’s (and my) positions are subject to the same frame-dependency as anyone else’s, but this is no more self-refuting or paradoxical than to say that all truth statements are made in a natural language that not everyone understands, including this one.

This point goes to the heart of Zabala’s book, as well as to the mistaken concerns about the hermeneutic tradition he defends. To say, with Zabala, that “there is no ‘neutral observation language’ that can erase human differences,” and that “these differences are not the source of our problems but rather the only possible route to their provisional solution,” is not to embrace or give succor to those making power grabs using bald assertions of “alternative facts,” but the very opposite. It is to say that “facts, information, and data by themselves do nothing. ‘Facts remain robust,’ as [philosopher of science Bruno] Latour says, ‘only when they are supported by a common culture, by institutions that can be trusted, by a more or less decent public life, by more or less reliable media.’” Let’s be quick to douse the realist canard that is sure to arise at this point — that relativist arguments are self-negating since, if all statements of fact are subject to cultural, historical, and institutional contexts, then so is this one — by stating the obvious: of course Zabala’s (and my) positions are subject to the same frame-dependency as anyone else’s, but this is no more self-refuting or paradoxical than to say that all truth statements are made in a natural language that not everyone understands, including this one. In its different versions, the tale has several recurring elements, though not all of them are present in every case. The chief one is the jealousy that rages in a beautiful mother (or stepmother, or mother-in-law) for her even more beautiful daughter. Then there is the mirror (or sometimes the sun or the moon and, in one version, a trout in a deep well) that reflects back to the mother the truth about her own beauty being surpassed. Someone is sent to kill the girl in the forest, sometimes a huntsman but occasionally an old woman or a witch; beguiled by the child’s beauty, they set her free, returning to the mother with a bloodstained shirt or an animal’s entrails. Lost in the forest, the child often comes upon a house in which to shelter. It might be lived in by untidy dwarfs (this gave Disney an opportunity to make Snow White into a perfect 1930s housewife), but often its inhabitants are immaculately tidy dwarfs (as in the Grimms’ version), and occasionally they are gangs of robbers or even brothers who look upon Snow White as a sister to be protected. Sometimes there are seven of them in the house, sometimes twelve.

In its different versions, the tale has several recurring elements, though not all of them are present in every case. The chief one is the jealousy that rages in a beautiful mother (or stepmother, or mother-in-law) for her even more beautiful daughter. Then there is the mirror (or sometimes the sun or the moon and, in one version, a trout in a deep well) that reflects back to the mother the truth about her own beauty being surpassed. Someone is sent to kill the girl in the forest, sometimes a huntsman but occasionally an old woman or a witch; beguiled by the child’s beauty, they set her free, returning to the mother with a bloodstained shirt or an animal’s entrails. Lost in the forest, the child often comes upon a house in which to shelter. It might be lived in by untidy dwarfs (this gave Disney an opportunity to make Snow White into a perfect 1930s housewife), but often its inhabitants are immaculately tidy dwarfs (as in the Grimms’ version), and occasionally they are gangs of robbers or even brothers who look upon Snow White as a sister to be protected. Sometimes there are seven of them in the house, sometimes twelve.