Rudrangshu Mukherjee reviews Partha K. Chatterjee’s I Am The People, in The India Forum:

Rudrangshu Mukherjee reviews Partha K. Chatterjee’s I Am The People, in The India Forum:

Populism as an instrument of political practice was first witnessed in India under the prime ministership of Indira Gandhi. The practice grew more common, cutting across political parties, when after the Emergency the Congress began to lose its popularity especially at the state-level and then in the 1990s at the national level. Chatterjee delineates two levels at which populism works — the nation state and the people-nation. The formation of the latter, he says, has a long history which is written about mostly in the regional languages. The federal structure of the Indian Constitution creates space for this dual practice of populism. The characteristic, almost definitional feature of populism is that government policies are designed to benefit large sections of the electorate to win votes. Winning the next election appears as the principal goal of populist regimes rather than social and economic transformation. Populist regimes have at their helm a leader who projects herself as the benefactor and protector of the people and is invariably authoritarian in style and not averse to crushing any opposition by force.

At the national level, Chatterjee focuses on the character of the government under Narendra Modi who came to power promising change and development. This brought to him the unstinting support of big business (who funded his campaign and his party) and the enthusiastic support of an upwardly mobile younger generation. The hope was that Modi would step on the accelerator of economic growth and reform. This hope has evaporated because of the state of the global economy and the government’s unwillingness to take forward economic reforms.

More here.

Alex Gourevitch and Corey Robin in Polity:

Alex Gourevitch and Corey Robin in Polity: Inequality is neither economic nor technological; it is ideological and political.” Thomas Piketty’s latest book,

Inequality is neither economic nor technological; it is ideological and political.” Thomas Piketty’s latest book,  How will we live, or be forced to live, after the pandemic? “I don’t know” is—

How will we live, or be forced to live, after the pandemic? “I don’t know” is— Recently, the Federal Reserve announced that it would be loosening its lending guidelines so that more corporations, even those with massive pre-existing debts, could take part in the bailout feeding frenzy.

Recently, the Federal Reserve announced that it would be loosening its lending guidelines so that more corporations, even those with massive pre-existing debts, could take part in the bailout feeding frenzy.  On a freezing December day in 1386, at an old priory in Paris that today is a museum of science and technology—a temple of human reason—an eager crowd of thousands gathered to watch two knights fight a duel to the death with lance and sword and dagger. A beautiful young noblewoman, dressed all in black and exposed to the crowd’s stares, anxiously awaited the outcome. The trial by combat would decide whether she had told the truth—and thus whether she would live or die. Like today, sexual assault and rape often went unpunished and even unreported in the Middle Ages. But a public accusation of rape, at the time a capital offense and often a cause for scandalous rumors endangering the honor of those involved, could have grave consequences for both accuser and accused, especially among the nobility.

On a freezing December day in 1386, at an old priory in Paris that today is a museum of science and technology—a temple of human reason—an eager crowd of thousands gathered to watch two knights fight a duel to the death with lance and sword and dagger. A beautiful young noblewoman, dressed all in black and exposed to the crowd’s stares, anxiously awaited the outcome. The trial by combat would decide whether she had told the truth—and thus whether she would live or die. Like today, sexual assault and rape often went unpunished and even unreported in the Middle Ages. But a public accusation of rape, at the time a capital offense and often a cause for scandalous rumors endangering the honor of those involved, could have grave consequences for both accuser and accused, especially among the nobility. Catherine the Great is a monarch mired in misconception. Derided both in her day and in modern times as a hypocritical warmonger with an unnatural sexual appetite, Catherine was a woman of contradictions whose brazen exploits have long overshadowed the accomplishments that won her “the Great” moniker in the first place.

Catherine the Great is a monarch mired in misconception. Derided both in her day and in modern times as a hypocritical warmonger with an unnatural sexual appetite, Catherine was a woman of contradictions whose brazen exploits have long overshadowed the accomplishments that won her “the Great” moniker in the first place. Beginning thousands of years before the first dairy restaurant appeared, Katchor’s book attempts to explicate the laws of kashruth—the separation of milk and meat—and other dietary notions and origin myths. (The mixture of causal logic and total irrationality recalls Katchor’s musical-theater piece The Slug Bearers of Kayrol Island, in which exploited workers transport tiny lead weights to place inside and give heft to small appliances.) Coffeehouse culture stimulates the Enlightenment. Radical puritans imagine a prelapsarian Hebrew vegetarian diet while, having internalized certain liberal values advanced by the French Revolution, eighteenth-century Parisians invent the “restaurant” and the “menu,” consecrated to individual rights and freedom of choice.

Beginning thousands of years before the first dairy restaurant appeared, Katchor’s book attempts to explicate the laws of kashruth—the separation of milk and meat—and other dietary notions and origin myths. (The mixture of causal logic and total irrationality recalls Katchor’s musical-theater piece The Slug Bearers of Kayrol Island, in which exploited workers transport tiny lead weights to place inside and give heft to small appliances.) Coffeehouse culture stimulates the Enlightenment. Radical puritans imagine a prelapsarian Hebrew vegetarian diet while, having internalized certain liberal values advanced by the French Revolution, eighteenth-century Parisians invent the “restaurant” and the “menu,” consecrated to individual rights and freedom of choice. What is it you see, asks Rachael Z. DeLue, in Romare Bearden’s artwork? Why is it you just can’t stop looking? How is it they remain, decades after his death, sources of what Wallace Stevens calls “imperishable bliss”?

What is it you see, asks Rachael Z. DeLue, in Romare Bearden’s artwork? Why is it you just can’t stop looking? How is it they remain, decades after his death, sources of what Wallace Stevens calls “imperishable bliss”? When I was a kid, I adored going over to my grandmother’s house and exploring her art room. To reach it, I wound past my grandmother’s collections of things in the living room and hall, most in service of her

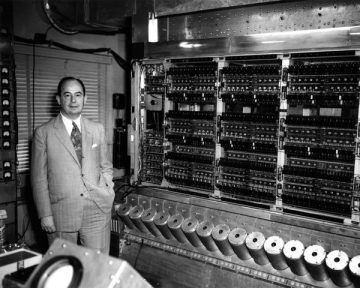

When I was a kid, I adored going over to my grandmother’s house and exploring her art room. To reach it, I wound past my grandmother’s collections of things in the living room and hall, most in service of her  That John von Neumann was one of the supreme intellects humanity has produced should be a statement beyond dispute. Both the lightning fast speed of his mind and the astonishing range of fields he made seminal contributions to made him a legend in his own lifetime. When he died in 1957 at the young age of 56 it was a huge loss; the loss of a great mathematician, a great polymath and to many, a great patriotic American who had done much to improve his country’s advantage in cutting-edge weaponry.

That John von Neumann was one of the supreme intellects humanity has produced should be a statement beyond dispute. Both the lightning fast speed of his mind and the astonishing range of fields he made seminal contributions to made him a legend in his own lifetime. When he died in 1957 at the young age of 56 it was a huge loss; the loss of a great mathematician, a great polymath and to many, a great patriotic American who had done much to improve his country’s advantage in cutting-edge weaponry. INDIAN CINEMA LOVES LOVE.

INDIAN CINEMA LOVES LOVE. If anybody profited from the war, it was us: its children. Apart from having survived it, we were richly provided with stuff to romanticize or to fantasize about. In addition to the usual childhood diet of Dumas and Jules Verne, we had military paraphernalia, which always goes well with boys. With us, it went exceptionally well, since it was our country that won the war.

If anybody profited from the war, it was us: its children. Apart from having survived it, we were richly provided with stuff to romanticize or to fantasize about. In addition to the usual childhood diet of Dumas and Jules Verne, we had military paraphernalia, which always goes well with boys. With us, it went exceptionally well, since it was our country that won the war.