Philippa Snow at The Point:

While there is no doubt that some version of the actress Kathryn Hahn existed prior to 2013, it seems to me to be appropriate to say that Kathryn Hahn the way we know her best—Hahn the bohemian horndog, the self-loathing yummy mummy with a graduate degree in English literature—made her onscreen debut that year in Afternoon Delight, a minor indie with some major hang-ups about sex work. Written and directed by Jill Soloway, the movie takes the unimaginative trope of a mid-lifer being reinvigorated by a young, hot and eccentric blonde, and makes it roughly 50 percent more intriguing by ensuring that the one having the midlife crisis is in fact a woman: Rachel, a bored stay-at-home mom who was once a jobbing writer, takes her husband to a strip club in the hopes that seeing other women naked might convince them to get naked with each other. Trying too hard to seem chill, she gets a lap dance from McKenna, a blonde, barely-legal stripper played by Juno Temple in the key of Paris Hilton. Hahn, as Rachel, plays the scene with four distinct moods: terrified, aroused, surprised to be aroused, and slightly dazed. Some psychic shift occurs, minor but vital to the plot.

While there is no doubt that some version of the actress Kathryn Hahn existed prior to 2013, it seems to me to be appropriate to say that Kathryn Hahn the way we know her best—Hahn the bohemian horndog, the self-loathing yummy mummy with a graduate degree in English literature—made her onscreen debut that year in Afternoon Delight, a minor indie with some major hang-ups about sex work. Written and directed by Jill Soloway, the movie takes the unimaginative trope of a mid-lifer being reinvigorated by a young, hot and eccentric blonde, and makes it roughly 50 percent more intriguing by ensuring that the one having the midlife crisis is in fact a woman: Rachel, a bored stay-at-home mom who was once a jobbing writer, takes her husband to a strip club in the hopes that seeing other women naked might convince them to get naked with each other. Trying too hard to seem chill, she gets a lap dance from McKenna, a blonde, barely-legal stripper played by Juno Temple in the key of Paris Hilton. Hahn, as Rachel, plays the scene with four distinct moods: terrified, aroused, surprised to be aroused, and slightly dazed. Some psychic shift occurs, minor but vital to the plot.

more here.

Some of the most thoughtful people I know find ways not to give the problems of animal agriculture any thought, just as I find ways to avoid thinking about climate change and income inequality, not to mention the paradoxes in my own eating life. One of the unexpected side effects of these months of sheltering in place is that it’s hard not to think about the things that are essential to who we are.

Some of the most thoughtful people I know find ways not to give the problems of animal agriculture any thought, just as I find ways to avoid thinking about climate change and income inequality, not to mention the paradoxes in my own eating life. One of the unexpected side effects of these months of sheltering in place is that it’s hard not to think about the things that are essential to who we are. There was supposed to be a peak.

There was supposed to be a peak.

When 61 people met for a choir practice in a church in Mount Vernon, Washington, on 10 March, everything seemed normal. For 2.5 hours the chorists sang, snacked on cookies and oranges, and sang some more. But one of them had been suffering for 3 days from what felt like a cold—and turned out to be COVID-19. In the following weeks, 53 choir members got sick, three were hospitalized, and two died, according to a

When 61 people met for a choir practice in a church in Mount Vernon, Washington, on 10 March, everything seemed normal. For 2.5 hours the chorists sang, snacked on cookies and oranges, and sang some more. But one of them had been suffering for 3 days from what felt like a cold—and turned out to be COVID-19. In the following weeks, 53 choir members got sick, three were hospitalized, and two died, according to a  We monster: According to Johnson, we cast out. But by casting out the monster, we cast in ourselves as that which is not-monster. That’s the simple formula, a process of inclusion by way of exclusion. But if the formula is, as formulas are, an equation, then both sides are equivalent, meaning that we must monster within as without, the monster thus monstered not gotten rid of, precisely, but held as an image, a template or test to be used to identify and expel more monsters—to go on monstering. I may only monster to the extent that I myself know the monstrous. Here echoes the fascist censor’s dilemma: If I recognize a critique of the state, then have I also not understood that the state is subject to critique, thereby betraying my own latent critique of the state? Too, the more I know of the monstrous, the better still my monstering—just as the monster knows us, how foolishly soft our throats, how stupidly open our windows. There is an intimacy in this: If, when we are children, we keep our monsters tucked under the bed, when we are adults they bed us, lodging in our chests and necks, penetrating our hearts, for it is another well-worn observation that the monster, as made, represents our desires as horrors, our horrors as desires. The vampire was emblematic of the love and fear of lust, that too-much of desire; Frankenstein’s creature, the love and fear of technology, that too-much of savoir faire; our Jekyll hiding our outraging Hyde.

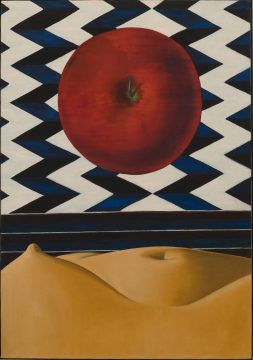

We monster: According to Johnson, we cast out. But by casting out the monster, we cast in ourselves as that which is not-monster. That’s the simple formula, a process of inclusion by way of exclusion. But if the formula is, as formulas are, an equation, then both sides are equivalent, meaning that we must monster within as without, the monster thus monstered not gotten rid of, precisely, but held as an image, a template or test to be used to identify and expel more monsters—to go on monstering. I may only monster to the extent that I myself know the monstrous. Here echoes the fascist censor’s dilemma: If I recognize a critique of the state, then have I also not understood that the state is subject to critique, thereby betraying my own latent critique of the state? Too, the more I know of the monstrous, the better still my monstering—just as the monster knows us, how foolishly soft our throats, how stupidly open our windows. There is an intimacy in this: If, when we are children, we keep our monsters tucked under the bed, when we are adults they bed us, lodging in our chests and necks, penetrating our hearts, for it is another well-worn observation that the monster, as made, represents our desires as horrors, our horrors as desires. The vampire was emblematic of the love and fear of lust, that too-much of desire; Frankenstein’s creature, the love and fear of technology, that too-much of savoir faire; our Jekyll hiding our outraging Hyde. It wasn’t until Luchita Hurtado was ninety-nine years old that she would witness the opening of her first museum retrospective. Titled “I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn,” the exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) showcases the artist’s paintings, drawings, and sketches spanning eighty years. Inside the galleries in early February, she addressed the press, smiling, “This is one of the best moments of my life.”

It wasn’t until Luchita Hurtado was ninety-nine years old that she would witness the opening of her first museum retrospective. Titled “I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn,” the exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) showcases the artist’s paintings, drawings, and sketches spanning eighty years. Inside the galleries in early February, she addressed the press, smiling, “This is one of the best moments of my life.” One might expect Ian Bremmer to be straightforwardly pessimistic in the current crisis. For one thing, the president of the Eurasia Group political risk consultancy is used to zipping around the world to meet business and political leaders. Now he is grounded and reckons any sort of new normal will take a very long time to emerge. “It’s weird,” he tells me down the phone from New York City. “I wasn’t prepared to put my life on hold for three years.” The US of all places is a gloomy spot at the moment, with more Covid-19 deaths than any other country and an increasingly ugly political mood ahead of November’s elections. Pessimism, of a sort, has been a good bet for Bremmer in the past. In 2011 he predicted a “G-Zero” world, an emerging power vacuum in international politics. The prediction has been borne out, he notes, both by trends evident at the time (a rising China reluctant to align with the West, a more self-contained US and a truculent Russia) and by others (technology driving populism, US energy independence, and the inequality bequeathed by the financial crisis) that have fully unfolded since.

One might expect Ian Bremmer to be straightforwardly pessimistic in the current crisis. For one thing, the president of the Eurasia Group political risk consultancy is used to zipping around the world to meet business and political leaders. Now he is grounded and reckons any sort of new normal will take a very long time to emerge. “It’s weird,” he tells me down the phone from New York City. “I wasn’t prepared to put my life on hold for three years.” The US of all places is a gloomy spot at the moment, with more Covid-19 deaths than any other country and an increasingly ugly political mood ahead of November’s elections. Pessimism, of a sort, has been a good bet for Bremmer in the past. In 2011 he predicted a “G-Zero” world, an emerging power vacuum in international politics. The prediction has been borne out, he notes, both by trends evident at the time (a rising China reluctant to align with the West, a more self-contained US and a truculent Russia) and by others (technology driving populism, US energy independence, and the inequality bequeathed by the financial crisis) that have fully unfolded since. The past couple of months have been heavy for us at The Scientist. Heavy for everyone. From our home offices, we’ve been tirelessly reporting on the global pandemic that continues to grip the world in its stranglehold. We are trying to stay atop a flood of information and stories that need telling as we also contend with challenges that most of us have never confronted, and none of us will likely soon forget. At the same time, we continue to search across the life sciences for other nuggets of research worth sharing. This month, our issue is focused on the science of memory. Our memories make us who we are, subconsciously driving our behaviors and dictating how we view the world. One of the most interesting things about memory is its imperfection. Rather than serving as a precise record of past events, our memories are more like concocted reflections, filtered and distilled from pure reality into a personal brew that is formulated by our own unique physiologies and emotional backgrounds. The wholly unique universe we each create—separate from but still tethered to the actual universe—is the product of electrical signals zapping through the lump of fatty flesh inside our skulls. Biology gives birth to something that exists outside the boundaries of biology.

The past couple of months have been heavy for us at The Scientist. Heavy for everyone. From our home offices, we’ve been tirelessly reporting on the global pandemic that continues to grip the world in its stranglehold. We are trying to stay atop a flood of information and stories that need telling as we also contend with challenges that most of us have never confronted, and none of us will likely soon forget. At the same time, we continue to search across the life sciences for other nuggets of research worth sharing. This month, our issue is focused on the science of memory. Our memories make us who we are, subconsciously driving our behaviors and dictating how we view the world. One of the most interesting things about memory is its imperfection. Rather than serving as a precise record of past events, our memories are more like concocted reflections, filtered and distilled from pure reality into a personal brew that is formulated by our own unique physiologies and emotional backgrounds. The wholly unique universe we each create—separate from but still tethered to the actual universe—is the product of electrical signals zapping through the lump of fatty flesh inside our skulls. Biology gives birth to something that exists outside the boundaries of biology. “Only when the tide goes out,” Warren Buffett observed, “do you discover who’s been swimming naked.” For our society, the Covid-19 pandemic represents an ebb tide of historic proportions, one that is laying bare vulnerabilities and inequities that in normal times have gone undiscovered. Nowhere is this more evident than in the American food system. A series of shocks has exposed weak links in our food chain that threaten to leave grocery shelves as patchy and unpredictable as those in the former Soviet bloc. The very system that made possible the bounty of the American supermarket—its vaunted efficiency and ability to “pile it high and sell it cheap”—suddenly seems questionable, if not misguided. But the problems the novel coronavirus has revealed are not limited to the way we produce and distribute food. They also show up on our plates, since the diet on offer at the end of the industrial food chain is linked to precisely the types of chronic disease that render us more vulnerable to Covid-19.

“Only when the tide goes out,” Warren Buffett observed, “do you discover who’s been swimming naked.” For our society, the Covid-19 pandemic represents an ebb tide of historic proportions, one that is laying bare vulnerabilities and inequities that in normal times have gone undiscovered. Nowhere is this more evident than in the American food system. A series of shocks has exposed weak links in our food chain that threaten to leave grocery shelves as patchy and unpredictable as those in the former Soviet bloc. The very system that made possible the bounty of the American supermarket—its vaunted efficiency and ability to “pile it high and sell it cheap”—suddenly seems questionable, if not misguided. But the problems the novel coronavirus has revealed are not limited to the way we produce and distribute food. They also show up on our plates, since the diet on offer at the end of the industrial food chain is linked to precisely the types of chronic disease that render us more vulnerable to Covid-19. Humans build machines, in part, to relieve themselves from the burden of work on difficult, repetitive tasks. And yet, despite the fact that machines are everywhere, most of us are still working pretty hard. But maybe that’s about to change. Futurists like John Danaher believe that society is finally on the brink of making a transition to a world in which work would be optional, rather than mandatory — and he thinks that’s a very good thing. It will take some adjusting, personally as well as economically, but he envisions a future in which human creativity and artistic impulse can flourish in a world free of the demands of working for a living. We talk about what that would entail, whether it’s realistic, and what comes next.

Humans build machines, in part, to relieve themselves from the burden of work on difficult, repetitive tasks. And yet, despite the fact that machines are everywhere, most of us are still working pretty hard. But maybe that’s about to change. Futurists like John Danaher believe that society is finally on the brink of making a transition to a world in which work would be optional, rather than mandatory — and he thinks that’s a very good thing. It will take some adjusting, personally as well as economically, but he envisions a future in which human creativity and artistic impulse can flourish in a world free of the demands of working for a living. We talk about what that would entail, whether it’s realistic, and what comes next.

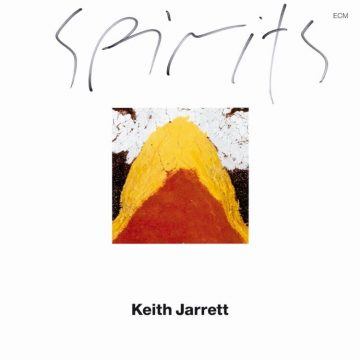

On July 7, 2013, Keith Jarrett bracingly took to the stage at the Umbria Jazz Festival in Perugia, Italy. The momentousness of the occasion was not lost on anyone: just six years earlier, Jarrett had become the first artist to ever be banned from the festival by director Carlo Pagnotta, for delivering a profanity-ridden condemnation of photographers in the audience. Seeking to avoid a similar incident this time around, Pagnotta issued a preemptive plea to the crowd to put their cameras away and to greet Jarrett with a standing ovation.

On July 7, 2013, Keith Jarrett bracingly took to the stage at the Umbria Jazz Festival in Perugia, Italy. The momentousness of the occasion was not lost on anyone: just six years earlier, Jarrett had become the first artist to ever be banned from the festival by director Carlo Pagnotta, for delivering a profanity-ridden condemnation of photographers in the audience. Seeking to avoid a similar incident this time around, Pagnotta issued a preemptive plea to the crowd to put their cameras away and to greet Jarrett with a standing ovation. No emotion stands nearer to the foundational myths of the human social order than shame. In the beginning, Adam and Eve stood together ‘both naked, the man and his wife, and were not ashamed’. And then they ate of the tree of knowledge; their eyes opened; they knew they were naked; they covered themselves with fig leaves. Their shame was what told God they had fallen and become humans of our sort. Protagoras tells Socrates that after Prometheus had distinguished humans from other animals by giving them fire, Zeus gave them both shame and justice so that they could live together in harmony.

No emotion stands nearer to the foundational myths of the human social order than shame. In the beginning, Adam and Eve stood together ‘both naked, the man and his wife, and were not ashamed’. And then they ate of the tree of knowledge; their eyes opened; they knew they were naked; they covered themselves with fig leaves. Their shame was what told God they had fallen and become humans of our sort. Protagoras tells Socrates that after Prometheus had distinguished humans from other animals by giving them fire, Zeus gave them both shame and justice so that they could live together in harmony. IN A TELEGRAM SENT

IN A TELEGRAM SENT