Tia Olivia Serves Wallace Stevens a Cuban Egg

The ration books voided, there was little to eat,

so Tía Olivia ruffled four hens to serve Stevens

a fresh criollo egg. The singular image lay limp,

floating in a circle of miniature roses and vines

etched around the edges of the rough dish.

The saffron, inhuman soul staring at Stevens

who asks what yolk is this, so odd a yellow?

Tell me Señora, if you know, he petitions,

what exactly is the color of this temptation:

I can see a sun, but it is not the color of suns

nor of sunflowers, nor the yellows of Van Gogh,

it is neither corn nor school pencil, as it is,

so few things are yellow, this, even more precise.

He shakes some salt, eye to eye hypothesizing:

a carnival of hues under the gossamer membrane,

a liqueur of convoluted colors, quarter-part orange,

imbued shadows, watercolors running a song

down the spine of praying stems, but what, then,

of the color of the stems, what green for the leaves,

what color the flowers; what of order for our eyes

if I can not name this elusive yellow, Señora?

Intolerant, Tía Olivia bursts open Stevens’s yolk,

plunging into it with a sharp piece of Cuban toast:

It is yellow, she says, amarillo y nada más, bien?

The unleashed pigments begin to fill the plate,

overflow onto the embroidered place mats,

stream down the table and through the living room

setting all the rocking chairs in motion then

over the mill tracks cutting through cane fields,

a viscous mass downing palm trees and shacks.

In its frothy wake whole choirs of church ladies

clutch their rosary beads and sing out in Latin,

exhausted macheteros wade in the stream,

holding glinting machetes overhead with one arm;

cafeteras, ’57 Chevys, uniforms and empty bottles,

mangy dogs and fattened pigs saved from slaughter,

Soviet jeeps, Bohemia magazines, park benches,

all carried in the egg lava carving the molested valley

and emptying into the sea. Yellow, Stevens relents,

Yes. But then what the color of the sea, Señora?

by Richard Blanco

from City of a Hundred Fires

University of Pittsburg Press, 1998

In 2019, 62 worshippers performing Friday prayers were killed by a bomb blast in Nangarhar. Back in 2002, a fire broke out at a girl’s school in Makkah. Fifteen young girls died and 50 injured, allegedly because they were beaten back to go inside: they had not covered their heads. In 1987, more than 400 unarmed pilgrims, mostly Iranians, were killed in Makkah during a protest. The list goes on. One fact stands out: most of the outpouring of anger, sympathy and concern came from non-Muslim organisations, people and countries. Muslims were, by and large, silent. Even as the world seems to have come closer, with a more formalised structure of human rights, it has regressed into increasing hatred and acts of violence against the ‘other’, whoever it might be. It took the Christians six centuries of religiously supported wars and torture against Muslims and Jews to decide that they could safely replace religion with science. They colonised, ridiculed Muslims, spread false rumours, destroyed traditions of Muslim scholarship and weakened Muslim societies through carefully orchestrated propaganda. Islamophobia has increased since 9/11 with Muslims being held in Guantanamo Bay prison and tortured. Very few Muslim governments stood up to help them.

In 2019, 62 worshippers performing Friday prayers were killed by a bomb blast in Nangarhar. Back in 2002, a fire broke out at a girl’s school in Makkah. Fifteen young girls died and 50 injured, allegedly because they were beaten back to go inside: they had not covered their heads. In 1987, more than 400 unarmed pilgrims, mostly Iranians, were killed in Makkah during a protest. The list goes on. One fact stands out: most of the outpouring of anger, sympathy and concern came from non-Muslim organisations, people and countries. Muslims were, by and large, silent. Even as the world seems to have come closer, with a more formalised structure of human rights, it has regressed into increasing hatred and acts of violence against the ‘other’, whoever it might be. It took the Christians six centuries of religiously supported wars and torture against Muslims and Jews to decide that they could safely replace religion with science. They colonised, ridiculed Muslims, spread false rumours, destroyed traditions of Muslim scholarship and weakened Muslim societies through carefully orchestrated propaganda. Islamophobia has increased since 9/11 with Muslims being held in Guantanamo Bay prison and tortured. Very few Muslim governments stood up to help them. The story began earlier this week, when Yoho reportedly approached Ocasio-Cortez on the Capitol steps to inform her that she was, among other things, “disgusting” and “out of your freaking mind.” His analysis was directed at her (hardly novel) public statements that poverty and unemployment are root causes of the recent spike in crime rates in New York. On matters of criminal-justice reform, Yoho is of a decidedly conservative bent. Not long ago, he voted against making lynching a federal hate crime, saying that such a law would be a regrettable instance of federal “overreach.” According to a reporter for

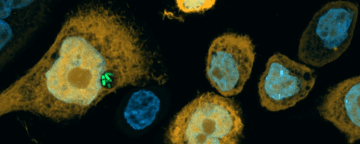

The story began earlier this week, when Yoho reportedly approached Ocasio-Cortez on the Capitol steps to inform her that she was, among other things, “disgusting” and “out of your freaking mind.” His analysis was directed at her (hardly novel) public statements that poverty and unemployment are root causes of the recent spike in crime rates in New York. On matters of criminal-justice reform, Yoho is of a decidedly conservative bent. Not long ago, he voted against making lynching a federal hate crime, saying that such a law would be a regrettable instance of federal “overreach.” According to a reporter for  Melanie Rutkowski, PhD, of UVA’s Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Cancer Biology, found that

Melanie Rutkowski, PhD, of UVA’s Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Cancer Biology, found that  Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg grew up with a solid old-school Brooklyn accent. She displays no trace of it in recordings of her work as a young litigator, but today, one can hear shades of it in her speech on and off the court. Why?

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg grew up with a solid old-school Brooklyn accent. She displays no trace of it in recordings of her work as a young litigator, but today, one can hear shades of it in her speech on and off the court. Why? There’s a

There’s a  When moral visions clash, it’s common for people to assume their opponents have bad motives rather than different perspectives. And it’s usually wrong. If you advocate some policy you believe will save lives, whether it’s a plan for fighting COVID-19, increasing health-care coverage, or reducing homicide, your opponents probably don’t oppose your plan because they want more people to die. They may think their own plan will save lives, or they may be concerned about other values entirely. You may very well have fundamental moral disagreements with them, but the thing you hate most about their position probably isn’t what’s driving them.

When moral visions clash, it’s common for people to assume their opponents have bad motives rather than different perspectives. And it’s usually wrong. If you advocate some policy you believe will save lives, whether it’s a plan for fighting COVID-19, increasing health-care coverage, or reducing homicide, your opponents probably don’t oppose your plan because they want more people to die. They may think their own plan will save lives, or they may be concerned about other values entirely. You may very well have fundamental moral disagreements with them, but the thing you hate most about their position probably isn’t what’s driving them. Cyan (pronounced SIGH-ann) is the color that emanates from a calm sea not far offshore on a clear day as the blue of the sky is reflected in salt water awash over yellow sand. You can see it for yourself in postcards mailed from coastal resorts or, if you are at a resort, from a vantage point somewhere above the beach—from a cliff, say, or lacking cliffs, from atop a palm tree. Various shades of cyan form the background to the ad for Swarovski (whatever that is) on page 13 of the April 2005 issue of Gourmet magazine. To create a highly saturated cyan on your own, you might pour 1/4 cup of Arm & Hammer’s Powerfully Clean Naturally Fresh Clean Burst laundry detergent onto the whites in your next load of wash (presumably Arm & Hammer adds the pigment to its product in order to provoke association with what we imagine to be the pristine purity of tropical seas). Also, you might search for “cyan” at wikipedia.org, where a resplendent rectangle of the color is on display, along with a succinct definition: “Cyan is a pure spectral color, but the same hue can also be generated by mixing equal amounts of green and blue light. As such, cyan is the complement of red: cyan pigments absorb red light. Cyan is sometimes called blue-green or turquoise and often goes undistinguished from light blue.”

Cyan (pronounced SIGH-ann) is the color that emanates from a calm sea not far offshore on a clear day as the blue of the sky is reflected in salt water awash over yellow sand. You can see it for yourself in postcards mailed from coastal resorts or, if you are at a resort, from a vantage point somewhere above the beach—from a cliff, say, or lacking cliffs, from atop a palm tree. Various shades of cyan form the background to the ad for Swarovski (whatever that is) on page 13 of the April 2005 issue of Gourmet magazine. To create a highly saturated cyan on your own, you might pour 1/4 cup of Arm & Hammer’s Powerfully Clean Naturally Fresh Clean Burst laundry detergent onto the whites in your next load of wash (presumably Arm & Hammer adds the pigment to its product in order to provoke association with what we imagine to be the pristine purity of tropical seas). Also, you might search for “cyan” at wikipedia.org, where a resplendent rectangle of the color is on display, along with a succinct definition: “Cyan is a pure spectral color, but the same hue can also be generated by mixing equal amounts of green and blue light. As such, cyan is the complement of red: cyan pigments absorb red light. Cyan is sometimes called blue-green or turquoise and often goes undistinguished from light blue.”

Even though the year is only a little more than halfway gone, 2020 has understandably been filled with talk about the “solace” of reading. More so than in any previous year in living memory, readers have been diving into books in order to escape the harsh realities of the outside world. In her new book “Austen Years: A Memoir in Five Novels,” award-winning author Rachel Cohen writes of exactly this kind of solace-seeking. While dealing with her father’s death and the birth of her daughter, Cohen found herself in a readerly relationship with the novels of Jane Austen that was more fixed, almost more compulsory, than anything she’d previously imagined for herself. In the opening pages, she muses that “if you had told me that years were coming when I would hardly pick up another serious writer with any real concentration, that the doings of a few English families would come to define almost the entire territory of my reading imagination, and that I would reach a point of such familiarity that I would simply let Austen’s books fall open and read a sentence or two as people in other times and places might use an almanac to soothe and predict, I would have been appalled.”

Even though the year is only a little more than halfway gone, 2020 has understandably been filled with talk about the “solace” of reading. More so than in any previous year in living memory, readers have been diving into books in order to escape the harsh realities of the outside world. In her new book “Austen Years: A Memoir in Five Novels,” award-winning author Rachel Cohen writes of exactly this kind of solace-seeking. While dealing with her father’s death and the birth of her daughter, Cohen found herself in a readerly relationship with the novels of Jane Austen that was more fixed, almost more compulsory, than anything she’d previously imagined for herself. In the opening pages, she muses that “if you had told me that years were coming when I would hardly pick up another serious writer with any real concentration, that the doings of a few English families would come to define almost the entire territory of my reading imagination, and that I would reach a point of such familiarity that I would simply let Austen’s books fall open and read a sentence or two as people in other times and places might use an almanac to soothe and predict, I would have been appalled.” When

When  On this week’s books podcast, my guess is Oxford University’s Professor of European Archaeology, Chris Gosden. Chris’s new book The History of Magic: From Alchemy to Witchcraft, From the Ice Age to the Present opens up what he sees as a side of human history that has been occluded by propaganda from science and religion. Accordingly, he delves back to evidence from the earliest human settlements all over the world to learn about our magical past – one thread in what he calls the ‘triple-helix’ of our cultural history. He tells me why John Dee got a bad rap, where magic wands came from – and why, unusually as an academic, he argues that magic isn’t just an anthropological curiosity but might, in fact, have something useful to teach us.

On this week’s books podcast, my guess is Oxford University’s Professor of European Archaeology, Chris Gosden. Chris’s new book The History of Magic: From Alchemy to Witchcraft, From the Ice Age to the Present opens up what he sees as a side of human history that has been occluded by propaganda from science and religion. Accordingly, he delves back to evidence from the earliest human settlements all over the world to learn about our magical past – one thread in what he calls the ‘triple-helix’ of our cultural history. He tells me why John Dee got a bad rap, where magic wands came from – and why, unusually as an academic, he argues that magic isn’t just an anthropological curiosity but might, in fact, have something useful to teach us.

My limited knowledge of Scots and Scottish English when I was young was based on caricatures in comics, particularly ‘

My limited knowledge of Scots and Scottish English when I was young was based on caricatures in comics, particularly ‘ Schneider: It depends upon the larger social and political setting. Several large research projects are currently trying to put AI inside the brain and peripheral nervous system. They aim to hook you to the cloud without the intermediary of a keyboard. For corporations doing this, such as Neuralink, Facebook and Kernel, your brain and body is an arena for future profit. Without proper legislative guardrails, your thoughts and biometric data could be sold to the highest bidder, and authoritarian dictatorships will have the ultimate mind control device. So, privacy safeguards are essential.

Schneider: It depends upon the larger social and political setting. Several large research projects are currently trying to put AI inside the brain and peripheral nervous system. They aim to hook you to the cloud without the intermediary of a keyboard. For corporations doing this, such as Neuralink, Facebook and Kernel, your brain and body is an arena for future profit. Without proper legislative guardrails, your thoughts and biometric data could be sold to the highest bidder, and authoritarian dictatorships will have the ultimate mind control device. So, privacy safeguards are essential.