James L. Gibson and Joseph L. Sutherland at SSRN:

Over the course of the period from the heyday of McCarthyism to the present, the percentage of the American people not feeling free to express their views has tripled. In 2019, fully four in ten Americans engaged in self-censorship. Our analyses of both over-time and cross-sectional variability provide several insights into why people keep their mouths shut. We find that:

(1) Levels of self-censorship are related to affective polarization among the mass public, but not via an “echo chamber” effect because greater polarization is associated with more self-censorship.

(2) Levels of mass political intolerance bear no relationship to self-censorship, either at the macro- or micro-levels.

(3) Those who perceive a more repressive government are only slightly more likely to engage in self-censorship. And

(4) those possessing more resources (e.g., higher levels of education) report engaging in more self-censorship.

Together, these findings suggest the conclusion that one’s larger macro-environment has little to do with self-censorship. Instead, micro-environment sentiments — such as worrying that expressing unpopular views will isolate and alienate people from their friends, family, and neighbors — seem to drive self-censorship. We conclude with a brief discussion of the significance of our findings for larger democracy theory and practice.

More here.

This is not the usual bland political memoir offering yet another story of finding the American dream. In part, this is because Ilhan Omar is not another dull politician. That much is obvious from the waves she has made in Washington, DC since becoming a member of Congress in 2019. Omar, from Minnesota, and Rashida Tlaib, from Michigan, are the first two Muslim women elected to Congress. Along with two other women of colour, who are also in their first term, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ayanna Pressley, they are known as “the squad”. The 181-year-old ban on wearing religious head-wear in the House chamber was changed in 2019, allowing Omar to wear her hijab on the floor of Congress. While running for Congress, Omar admits, she was worried that this rule would keep her from being able to serve.

This is not the usual bland political memoir offering yet another story of finding the American dream. In part, this is because Ilhan Omar is not another dull politician. That much is obvious from the waves she has made in Washington, DC since becoming a member of Congress in 2019. Omar, from Minnesota, and Rashida Tlaib, from Michigan, are the first two Muslim women elected to Congress. Along with two other women of colour, who are also in their first term, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ayanna Pressley, they are known as “the squad”. The 181-year-old ban on wearing religious head-wear in the House chamber was changed in 2019, allowing Omar to wear her hijab on the floor of Congress. While running for Congress, Omar admits, she was worried that this rule would keep her from being able to serve. Helen Fisher first appeared in Nautilus in 2015 with her article, “

Helen Fisher first appeared in Nautilus in 2015 with her article, “ Andrew Gelman over at his website:

Andrew Gelman over at his website: Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins interviews Roberto Unger in The Nation:

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins interviews Roberto Unger in The Nation: Sam Moyn over at the Quincy Institute:

Sam Moyn over at the Quincy Institute: Sarah Stoller in Aeon:

Sarah Stoller in Aeon: Hassina Mechaï over at the Verso blog:

Hassina Mechaï over at the Verso blog: When I think that it won’t hurt too much, I imagine the children I will not have. Would they be more like me or my partner? Would they have inherited my thatch of hair, our terrible eyesight? Mostly, a child is so abstract to me, living with high rent, student debt, no property and no room, that the absence barely registers. But sometimes I suddenly want a daughter with the same staggering intensity my father felt when he first cradled my tiny body in his big hands. I want to feel that reassuring weight, a reminder of the persistence of life.

When I think that it won’t hurt too much, I imagine the children I will not have. Would they be more like me or my partner? Would they have inherited my thatch of hair, our terrible eyesight? Mostly, a child is so abstract to me, living with high rent, student debt, no property and no room, that the absence barely registers. But sometimes I suddenly want a daughter with the same staggering intensity my father felt when he first cradled my tiny body in his big hands. I want to feel that reassuring weight, a reminder of the persistence of life. In early April, at the height of the pandemic lockdown, Gianpiero Petriglieri, an Italian business professor, suggested on Twitter that being forced to conduct much of our lives online was making us sick. The constant video calls and Zoom meetings were draining us because they go against our brain’s need for boundaries: here versus not here. “It’s easier being in each other’s presence, or in each other’s absence,” he wrote, “than in the constant presence of each other’s absence.”

In early April, at the height of the pandemic lockdown, Gianpiero Petriglieri, an Italian business professor, suggested on Twitter that being forced to conduct much of our lives online was making us sick. The constant video calls and Zoom meetings were draining us because they go against our brain’s need for boundaries: here versus not here. “It’s easier being in each other’s presence, or in each other’s absence,” he wrote, “than in the constant presence of each other’s absence.” I must admit

I must admit GIVEN THAT SHE

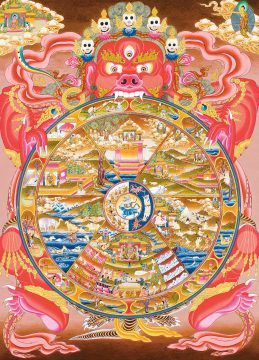

GIVEN THAT SHE In any case, for me—like many Buddhists, past and present—the most frightening part of karma isn’t a vision of torments in the next life, but the idea that my suffering in this life isn’t altogether random or circumstantial; it carries the trace of some previous action along with it. There’s something unbearable about causality when we think about it in the strictest terms: A virus, for example, can be transmitted through the simplest unconscious act, like scratching your nose with the same finger that was just wrapped around a subway pole. In contemporary physics, the limits of causality are explored in the field known as “quantum entanglement,” or what Einstein called “spooky action at a distance”: that is, the ability of distant entities to influence one another with no apparent force (like gravity) connecting them. Physicists know quantum entanglement happens, but how it works, and what power it exerts over everyday objects, is a subject of much debate.

In any case, for me—like many Buddhists, past and present—the most frightening part of karma isn’t a vision of torments in the next life, but the idea that my suffering in this life isn’t altogether random or circumstantial; it carries the trace of some previous action along with it. There’s something unbearable about causality when we think about it in the strictest terms: A virus, for example, can be transmitted through the simplest unconscious act, like scratching your nose with the same finger that was just wrapped around a subway pole. In contemporary physics, the limits of causality are explored in the field known as “quantum entanglement,” or what Einstein called “spooky action at a distance”: that is, the ability of distant entities to influence one another with no apparent force (like gravity) connecting them. Physicists know quantum entanglement happens, but how it works, and what power it exerts over everyday objects, is a subject of much debate. Of course, I had seen, next to the Gentleman’s Relish, the box of finely dusted Turkish delight, the halva, the packets of rosti; I had been with him to his birthplace in Romania and seen the places of his childhood, not once but twice; together with Alexander, I had been in the ancient forests with him, had picked wild raspberries and cracked open hazelnuts with a stone. I had helped him fill the box of Christmas gifts for our cousins stuck behind the Iron Curtain: chocolate, vitamins, medicine, Marmite, jam, tinned sardines, winter gloves and hats, stockings. But these things had featured only in the margin of my map of my father. At least, until that day when my friend asked: ‘Where’s your father from?’ More than thirty years have passed, and still I hover in the same state of postponed understanding, like the delayed response after the turning of a ship’s wheel or the pulling of a bell rope. Where was he from? Why do I need to know? Will I feel better if I do?

Of course, I had seen, next to the Gentleman’s Relish, the box of finely dusted Turkish delight, the halva, the packets of rosti; I had been with him to his birthplace in Romania and seen the places of his childhood, not once but twice; together with Alexander, I had been in the ancient forests with him, had picked wild raspberries and cracked open hazelnuts with a stone. I had helped him fill the box of Christmas gifts for our cousins stuck behind the Iron Curtain: chocolate, vitamins, medicine, Marmite, jam, tinned sardines, winter gloves and hats, stockings. But these things had featured only in the margin of my map of my father. At least, until that day when my friend asked: ‘Where’s your father from?’ More than thirty years have passed, and still I hover in the same state of postponed understanding, like the delayed response after the turning of a ship’s wheel or the pulling of a bell rope. Where was he from? Why do I need to know? Will I feel better if I do?