Shaj Mathew in The New Yorker:

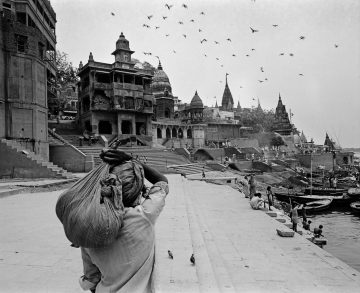

The Twice-Born,” a new memoir by Aatish Taseer, is troubled by a single plaintive question: Does a city steeped in tradition have a future in modern India? The setting is Benares, the spiritual capital of Hinduism, where more than five million pilgrims flock each year to worship, bathe, and burn their dead. Dying while in Benares, it is said, will release a Hindu from the cycle of reincarnation, and Taseer discovers an industry of death that’s alive and well in the city. He describes corpses that “sizzled away on funeral pyres,” as dinghies drifted on the Ganges amid smoke and marigolds. Taseer, to be clear, has not come to Benares to die. He’s in his thirties for most of the memoir, and, anyway, he’s not religious. His pilgrimage is secular; he seeks to filter the contradictions of present-day India through his life story. In the process, “The Twice-Born” becomes a moving, if maundering, riff on what it means to be modern. For Taseer, Benares incarnates a curious quality of modernity: the city makes anthropologists of the devout and believers of the skeptical. The book’s charm resides in the way the author orbits this tension between faith and rationality. He yearns to make sense of how “the laws of reason and the laws of magic . . . reached an easy harmony” in contemporary India.

The Twice-Born,” a new memoir by Aatish Taseer, is troubled by a single plaintive question: Does a city steeped in tradition have a future in modern India? The setting is Benares, the spiritual capital of Hinduism, where more than five million pilgrims flock each year to worship, bathe, and burn their dead. Dying while in Benares, it is said, will release a Hindu from the cycle of reincarnation, and Taseer discovers an industry of death that’s alive and well in the city. He describes corpses that “sizzled away on funeral pyres,” as dinghies drifted on the Ganges amid smoke and marigolds. Taseer, to be clear, has not come to Benares to die. He’s in his thirties for most of the memoir, and, anyway, he’s not religious. His pilgrimage is secular; he seeks to filter the contradictions of present-day India through his life story. In the process, “The Twice-Born” becomes a moving, if maundering, riff on what it means to be modern. For Taseer, Benares incarnates a curious quality of modernity: the city makes anthropologists of the devout and believers of the skeptical. The book’s charm resides in the way the author orbits this tension between faith and rationality. He yearns to make sense of how “the laws of reason and the laws of magic . . . reached an easy harmony” in contemporary India.

Taseer attempts to focus the book on his interactions with Brahmins, Hinduism’s priestly caste. (They are the twice-born of the memoir’s title, because they are considered to be born a second time upon their scholarly initiation.) But Taseer is foremost a wanderer, and the roving form of the book echoes his penchant for circularity. He writes as though Benares, in all its many dimensions, can be apprehended only through overlapping, fractal perspectives, one of which is his own.

Taseer’s relationship to himself is distinctly spectatorial; he cannot stop looking at himself looking at himself. “I saw everything as an Anglicized Indian watching an imaginary European or American visitor watch India,” he writes. “I wished I had a more direct relationship with my country. But any attempt to do so only made the self-observing selves multiply.”

More here.