Charaxos and Larichos

Say what you like about Charaxos,

that’s a fellow with a fat-bellied ship

always in some port or other.

What does Zeus care, or the rest of his gang?

Now you’d like me on my knees,

crying out to Hera, “Blah, blah, blah,

bring him home safe and free of warts,”

or blubbering, “Wah, wah, wah, thank you,

thank you, for curing my liver condition.”

Good grief, gods do what they like.

They call down hurricanes with a whisper

or send off a tsunami the way you would a love letter.

If they have a whim, they make some henchmen

fix it up, like those idiots in the Iliad.

A puff of smoke, a little fog, away goes the hero,

it’s happily ever after. As for Larichos,

that lay-a-bed lives for the pillow. If for once

he’d get off his ass, he might make something of himself.

Then from that reeking sewer of my life

I might haul up a bucket of spring water.

by Sappho

from Poetry, July/August 2016

Translated from the Greek by William Logan

In the summer of 1977, on a field trip in northern Patagonia, the American archaeologist Tom Dillehay made a stunning discovery. Digging by a creek in a nondescript scrubland called Monte Verde, in southern Chile, he came upon the remains of an ancient camp. A full excavation uncovered the trace wooden foundations of no fewer than 12 huts, plus one larger structure designed for tool manufacture and perhaps as an infirmary. In the large hut, Dillehay found gnawed bones, spear points, grinding tools and, hauntingly, a human footprint in the sand. The ancestral Patagonians—inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego and the Magellan Straits—had erected their domestic quarters using branches from the beech trees of a long-gone temperate forest, then covered them with the hides of vanished ice age species, including mastodons, saber-toothed cats, and giant sloths.

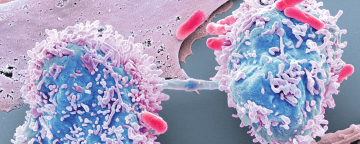

In the summer of 1977, on a field trip in northern Patagonia, the American archaeologist Tom Dillehay made a stunning discovery. Digging by a creek in a nondescript scrubland called Monte Verde, in southern Chile, he came upon the remains of an ancient camp. A full excavation uncovered the trace wooden foundations of no fewer than 12 huts, plus one larger structure designed for tool manufacture and perhaps as an infirmary. In the large hut, Dillehay found gnawed bones, spear points, grinding tools and, hauntingly, a human footprint in the sand. The ancestral Patagonians—inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego and the Magellan Straits—had erected their domestic quarters using branches from the beech trees of a long-gone temperate forest, then covered them with the hides of vanished ice age species, including mastodons, saber-toothed cats, and giant sloths. A breathalyzer designed to detect multiple cancers early is being tested in the UK. Several illnesses

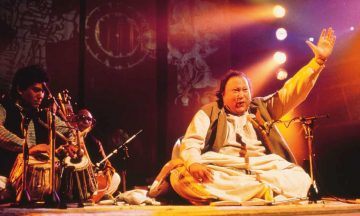

A breathalyzer designed to detect multiple cancers early is being tested in the UK. Several illnesses Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan In 1931, the Austrian logician Kurt Gödel pulled off arguably one of the most stunning intellectual achievements in history.

In 1931, the Austrian logician Kurt Gödel pulled off arguably one of the most stunning intellectual achievements in history. There are two boxes on a table, one red and one green. One contains a treasure. The red box is labelled “exactly one of the labels is true”. The green box is labelled “the treasure is in this box.”

There are two boxes on a table, one red and one green. One contains a treasure. The red box is labelled “exactly one of the labels is true”. The green box is labelled “the treasure is in this box.” WHAT IS A WOMAN’S MARGINAL UTILITY?

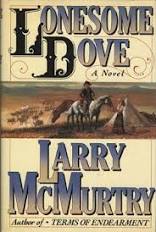

WHAT IS A WOMAN’S MARGINAL UTILITY? By the halfway point in my journey through Lonesome Dove two things started happening. As I began communicating my Keats-on-Chapman’s-Homer “discovery” to friends, it became clear that the book inspired something more akin to faith than admiration or love. People hadn’t just read the book; they had converted or pledged allegiance to it. When a friend came to dinner and saw my copy on the table she explained that she had been given the middle name MacRae, in honour of Gus. I fell prey to a kind of fanaticism myself, emailing an unsuspecting Zadie Smith to ask why anyone would bother with even a page of Saul Bellow when they could be immersed in Lonesome Dove. When she wrote back that she couldn’t bear Bellow or westerns I was tempted to respond, insanely, that it wasn’t a western. And yet – to deploy a favourite hesitation of Steiner’s – perhaps an underlying sanity or logic was at work.

By the halfway point in my journey through Lonesome Dove two things started happening. As I began communicating my Keats-on-Chapman’s-Homer “discovery” to friends, it became clear that the book inspired something more akin to faith than admiration or love. People hadn’t just read the book; they had converted or pledged allegiance to it. When a friend came to dinner and saw my copy on the table she explained that she had been given the middle name MacRae, in honour of Gus. I fell prey to a kind of fanaticism myself, emailing an unsuspecting Zadie Smith to ask why anyone would bother with even a page of Saul Bellow when they could be immersed in Lonesome Dove. When she wrote back that she couldn’t bear Bellow or westerns I was tempted to respond, insanely, that it wasn’t a western. And yet – to deploy a favourite hesitation of Steiner’s – perhaps an underlying sanity or logic was at work. In the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage, a team of scientists is shrunk to fit into a tiny submarine so that they can navigate their colleague’s vasculature and rid him of a deadly blood clot in his brain. This classic film is one of many such imaginative biological journeys that have made it to the big screen over the past several decades. At the same time, scientists have been working to make a similar vision a reality: tiny robots roaming the human body to detect and treat disease.

In the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage, a team of scientists is shrunk to fit into a tiny submarine so that they can navigate their colleague’s vasculature and rid him of a deadly blood clot in his brain. This classic film is one of many such imaginative biological journeys that have made it to the big screen over the past several decades. At the same time, scientists have been working to make a similar vision a reality: tiny robots roaming the human body to detect and treat disease.

I don’t believe in coincidences, at least not big ones. That’s why the sea change the sister arts of poetry, painting, and music underwent at the turn of the 20th century has always intrigued me. All of them veered off course at virtually the same time and in virtually the same way. To paraphrase Yul Brynner in The King and I, “It was a puzzlement.” It was as if a group of high achieving artists had met, mafia-style, in some non-disclosed location to plan mischief against the art world. It had all the hallmarks of a conspiracy. They would do something so radical, so scandalous that it would turn the art world on its head.

I don’t believe in coincidences, at least not big ones. That’s why the sea change the sister arts of poetry, painting, and music underwent at the turn of the 20th century has always intrigued me. All of them veered off course at virtually the same time and in virtually the same way. To paraphrase Yul Brynner in The King and I, “It was a puzzlement.” It was as if a group of high achieving artists had met, mafia-style, in some non-disclosed location to plan mischief against the art world. It had all the hallmarks of a conspiracy. They would do something so radical, so scandalous that it would turn the art world on its head. Are you racist? And, if so, how would I know? I used to think that a good gauge may be whether you call me a ‘Paki’, or assault me because of my skin colour, or deny me a job after seeing my name. But, no, these are just overt expressions of racism. Even if you show no hostility, or seek to discriminate, you’re probably still racist. You just don’t know it. Especially if you’re white. And if you protest about being labelled a racist, you are merely revealing what the US academic and diversity trainer Robin DiAngelo describes in the title of her bestselling book as your

Are you racist? And, if so, how would I know? I used to think that a good gauge may be whether you call me a ‘Paki’, or assault me because of my skin colour, or deny me a job after seeing my name. But, no, these are just overt expressions of racism. Even if you show no hostility, or seek to discriminate, you’re probably still racist. You just don’t know it. Especially if you’re white. And if you protest about being labelled a racist, you are merely revealing what the US academic and diversity trainer Robin DiAngelo describes in the title of her bestselling book as your  We gather empirical evidence about the nature of the world through our senses, and use that evidence to construct an image of the world in our minds. But not all senses are created equal; in practice, we tend to privilege vision, with hearing perhaps a close second. Ann-Sophie Barwich wants to argue that we should take smell more seriously, and that doing so will give us new insights into how the brain works. As a working philosopher and neuroscientist, she shares a wealth of fascinating information about how smell works, how it shapes the way we think, and what it all means for questions of free will and rationality.

We gather empirical evidence about the nature of the world through our senses, and use that evidence to construct an image of the world in our minds. But not all senses are created equal; in practice, we tend to privilege vision, with hearing perhaps a close second. Ann-Sophie Barwich wants to argue that we should take smell more seriously, and that doing so will give us new insights into how the brain works. As a working philosopher and neuroscientist, she shares a wealth of fascinating information about how smell works, how it shapes the way we think, and what it all means for questions of free will and rationality. Depression forces itself through the cracks of one’s life, finding the weak spots particular to the person it inundates. Like consciousness itself, depression seems to dwell in that hazy realm where matter and spirit meet, and we turn inward to pursue its elusive essence. Exploring what caused a person’s depression, however, what set it off on the particular course it ran, necessarily ends in an overdetermined tangle—one reason why the shelves overflow with depression memoirs. We keep trying to pin depression down, but fail again and again. Styron’s depression set upon him when he was around sixty years old, likely “triggered” when he suddenly gave up alcohol and began taking a dangerous sleeping medication. But as Styron meditates on what happened to him, the chain of causation extends ever backward—he realizes three main characters in his novels kill themselves, a fact that suggests the storm had been gathering for many years. Then he presses on to childhood wounds. Would a man who’d led a different life sink into depression after he quit drinking? Styron gets to the end of Darkness Visible and confesses, “The very number of hypotheses is testimony to the malady’s all but impenetrable mystery.”

Depression forces itself through the cracks of one’s life, finding the weak spots particular to the person it inundates. Like consciousness itself, depression seems to dwell in that hazy realm where matter and spirit meet, and we turn inward to pursue its elusive essence. Exploring what caused a person’s depression, however, what set it off on the particular course it ran, necessarily ends in an overdetermined tangle—one reason why the shelves overflow with depression memoirs. We keep trying to pin depression down, but fail again and again. Styron’s depression set upon him when he was around sixty years old, likely “triggered” when he suddenly gave up alcohol and began taking a dangerous sleeping medication. But as Styron meditates on what happened to him, the chain of causation extends ever backward—he realizes three main characters in his novels kill themselves, a fact that suggests the storm had been gathering for many years. Then he presses on to childhood wounds. Would a man who’d led a different life sink into depression after he quit drinking? Styron gets to the end of Darkness Visible and confesses, “The very number of hypotheses is testimony to the malady’s all but impenetrable mystery.” SURVEYING OUR CULTURAL LANDSCAPE through the prepositional prism of after is hardly a new approach among critics and historians writing on art during the past quarter century. Yet, as articulated in the title of Hal Foster’s new book, the premise is newly intriguing for being tethered to—and eclipsed in blunt rhetorical force by—the sad comedy of “farce.” Here Foster borrows the term from Marx’s famous adage regarding the French bourgeoisie’s willingness in 1851 to cede democratic values to a second Bonaparte emperor some fifty years after the first—a scenario that resonates strongly with our circumstances today, Foster suggests, insofar as Donald Trump’s arrival on the American scene must be understood not as a singularity but rather as another iteration of the authoritarian impulses that originally took root in the wake of 9/11. If “alternative facts” and conspiracy theories now flourish along the banks of the mainstream, they first needed the rich soil fertilized by the nationalist kitsch proffered at the start of the second Iraq war. To bolster his point, Foster cites novelist Milan Kundera’s observation that “in the realm of totalitarian kitsch all answers are given in advance and preclude any questions,” adding that such an epistemology met the fuel of populist affect at the dawn of the 2000s.

SURVEYING OUR CULTURAL LANDSCAPE through the prepositional prism of after is hardly a new approach among critics and historians writing on art during the past quarter century. Yet, as articulated in the title of Hal Foster’s new book, the premise is newly intriguing for being tethered to—and eclipsed in blunt rhetorical force by—the sad comedy of “farce.” Here Foster borrows the term from Marx’s famous adage regarding the French bourgeoisie’s willingness in 1851 to cede democratic values to a second Bonaparte emperor some fifty years after the first—a scenario that resonates strongly with our circumstances today, Foster suggests, insofar as Donald Trump’s arrival on the American scene must be understood not as a singularity but rather as another iteration of the authoritarian impulses that originally took root in the wake of 9/11. If “alternative facts” and conspiracy theories now flourish along the banks of the mainstream, they first needed the rich soil fertilized by the nationalist kitsch proffered at the start of the second Iraq war. To bolster his point, Foster cites novelist Milan Kundera’s observation that “in the realm of totalitarian kitsch all answers are given in advance and preclude any questions,” adding that such an epistemology met the fuel of populist affect at the dawn of the 2000s. Humans are almost constantly connected to devices and electronics that generate a significant amount of data about who they are and what they do. Many commercially available products like Fitbits, Garmin trackers, Apple watches and other smartwatches are designed to help users take control of their health, and tailor activities to their lifestyle. Even something as unobtrusive to wear as

Humans are almost constantly connected to devices and electronics that generate a significant amount of data about who they are and what they do. Many commercially available products like Fitbits, Garmin trackers, Apple watches and other smartwatches are designed to help users take control of their health, and tailor activities to their lifestyle. Even something as unobtrusive to wear as