Gary Greenberg in The Atlantic:

In 1886, Clark Bell, the editor of the journal of the Medico-Legal Society of New York, relayed to a physician named Pliny Earle a query bound to be of interest to his journal’s readers: Exactly what mental illnesses can be said to exist? In his 50-year career as a psychiatrist, Earle had developed curricula to teach medical students about mental disorders, co-founded the first professional organization of psychiatrists, and opened one of the first private psychiatric practices in the country. He had also run a couple of asylums, where he instituted novel treatment strategies such as providing education to the mentally ill. If any American doctor was in a position to answer Bell’s query, it was Pliny Earle.

In 1886, Clark Bell, the editor of the journal of the Medico-Legal Society of New York, relayed to a physician named Pliny Earle a query bound to be of interest to his journal’s readers: Exactly what mental illnesses can be said to exist? In his 50-year career as a psychiatrist, Earle had developed curricula to teach medical students about mental disorders, co-founded the first professional organization of psychiatrists, and opened one of the first private psychiatric practices in the country. He had also run a couple of asylums, where he instituted novel treatment strategies such as providing education to the mentally ill. If any American doctor was in a position to answer Bell’s query, it was Pliny Earle.

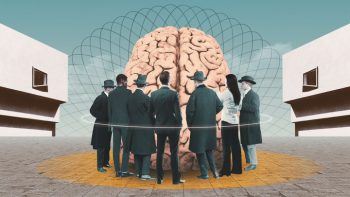

Earle responded with a letter unlikely to satisfy Bell. “In the present state of our knowledge,” he wrote, “no classification can be erected upon a pathological basis, for the simple reason that, with slight exceptions, the pathology of the disease is unknown.” Earle’s demurral was also a lament. During his career, he had watched with excitement as medicine, once a discipline rooted in experience and tradition, became a practice based on science. Doctors had treated vaguely named diseases like ague and dropsy with therapies like bloodletting and mustard plasters. Now they deployed chemical agents like vaccines to target diseases identified by their biological causes. But, as Earle knew, psychiatrists could not peer into a microscope to see the biological source of their patients’ suffering, which arose, they assumed, from the brain. They were stuck in the premodern past, dependent on “the apparent mental condition [his emphasis], as judged from the outward manifestations,” to devise diagnoses and treatments.

More here.