Ruth Williams in The Scientist:

Studies of blood samples from four rheumatoid arthritis patients collected over years has led to the discovery of an RNA profile that predicts an imminent flare-up of symptoms, according to a report in the New England Journal of Medicine today (July 15). The transcriptional signature also indicates that a type of fibroblast previously linked to the disease becomes enriched in the blood before migrating to the joints to wreak havoc. “The work is clearly a breakthrough in how patients with [rheumatoid arthritis] might be managed in the future,” Lawrence Steinman of Stanford University writes in an email to The Scientist. If such an RNA test were commercially developed, then “via a home test involving a mere finger stick, markers that precede a flare [would be] identified. This would allow the individual to consult with their physician and take necessary measures to avert such a flare,” continues Steinman, who studies autoimmune diseases but was not involved in the study.

Studies of blood samples from four rheumatoid arthritis patients collected over years has led to the discovery of an RNA profile that predicts an imminent flare-up of symptoms, according to a report in the New England Journal of Medicine today (July 15). The transcriptional signature also indicates that a type of fibroblast previously linked to the disease becomes enriched in the blood before migrating to the joints to wreak havoc. “The work is clearly a breakthrough in how patients with [rheumatoid arthritis] might be managed in the future,” Lawrence Steinman of Stanford University writes in an email to The Scientist. If such an RNA test were commercially developed, then “via a home test involving a mere finger stick, markers that precede a flare [would be] identified. This would allow the individual to consult with their physician and take necessary measures to avert such a flare,” continues Steinman, who studies autoimmune diseases but was not involved in the study.

Rheumatoid arthritis, in which the body’s immune system attacks the joints to cause swelling, stiffness, and pain, exhibits a waxing and waning of symptoms, as do many other autoimmune diseases. Even with treatment to suppress certain immune cells or cytokines, it is common for a patient to experience a couple of relapses each year, says study author Dana Orange, a clinical rheumatologist and researcher at Rockefeller University in the laboratory of Robert Darnell. Relapses in the disease are debilitating and can make life hard to plan, explains Orange. Patients “just don’t know when they are going to be blind-sided and incapacitated with a flare,” she says. Orange, Darnell, and colleagues therefore sought a way to predict such occurrences. Being a dynamic molecule, RNA “lends itself to profiling changes over time,” says Darnell, whose research focuses on RNA regulation in autoimmune and other diseases. “What we wanted to do,” he says, “was to design a study where we could have the RNA before a patient gets sick with a flare . . . to try and get signatures of what might be the antecedents.”

To this end the team recruited patients, via an ad in a newspaper, who were willing to collect tiny samples of their own blood—a few drops via a finger stick—each week and keep diaries of their symptoms. The patients also had clinical evaluations once a month. The team then sequenced the messenger RNA content of a selection of the blood samples—those representing baseline conditions and the weeks immediately prior to, during, and after a flare—to see whether and how the transcriptomes varied with the waxing and waning of symptoms. A total of 162 samples, taken from four patients over the course of one to four years, were sequenced and analyzed computationally. When they looked at the weeks preceding a flare up, “what jumped out was that something changed from the baseline,” says Darnell. Two weeks prior to a relapse, the team detected a change in the RNA profile that was consistent with an increased abundance of immune cells. “That gave us a hint that we were on the right track and that was exciting,” says Darnell, “but the big excitement came when we were looking at week -1.”

“There was a unique set of genes that were unexpected—they had signatures of stem cells and mesenchymal cells,” Darnell continues, and “it was not clear exactly what to make of that.”

More here.

Schneider: It depends upon the larger social and political setting. Several large research projects are currently trying to put AI inside the brain and peripheral nervous system. They aim to hook you to the cloud without the intermediary of a keyboard. For corporations doing this, such as Neuralink, Facebook and Kernel, your brain and body is an arena for future profit. Without proper legislative guardrails, your thoughts and biometric data could be sold to the highest bidder, and authoritarian dictatorships will have the ultimate mind control device. So, privacy safeguards are essential.

Schneider: It depends upon the larger social and political setting. Several large research projects are currently trying to put AI inside the brain and peripheral nervous system. They aim to hook you to the cloud without the intermediary of a keyboard. For corporations doing this, such as Neuralink, Facebook and Kernel, your brain and body is an arena for future profit. Without proper legislative guardrails, your thoughts and biometric data could be sold to the highest bidder, and authoritarian dictatorships will have the ultimate mind control device. So, privacy safeguards are essential.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle did not merely condone slavery, he defended it; he did not merely defend it, but defended it as beneficial to the slave. His view was that some people are, by nature, unable to pursue their own good, and best suited to be “living tools” for use by other people: “The slave is a part of the master, a living but separated part of his bodily frame.”

The Greek philosopher Aristotle did not merely condone slavery, he defended it; he did not merely defend it, but defended it as beneficial to the slave. His view was that some people are, by nature, unable to pursue their own good, and best suited to be “living tools” for use by other people: “The slave is a part of the master, a living but separated part of his bodily frame.” Studies of blood samples from four rheumatoid arthritis patients collected over years has led to the discovery of an RNA profile that predicts an imminent flare-up of symptoms, according to a report in the

Studies of blood samples from four rheumatoid arthritis patients collected over years has led to the discovery of an RNA profile that predicts an imminent flare-up of symptoms, according to a report in the  The most revealing

The most revealing  For several weeks I’ve been hunting up works by the English writer Sylvia Townsend Warner. Her long career, dedication, and daring—her uncompromising will to lead a life of her own, writing fiction that can’t simply be cornered by the term “eccentric,” crafting in her eighties some of the strangest stories ever to appear in The New Yorker—she’s one of the spine-stiffening writers. She makes a perfect quarantine companion.

For several weeks I’ve been hunting up works by the English writer Sylvia Townsend Warner. Her long career, dedication, and daring—her uncompromising will to lead a life of her own, writing fiction that can’t simply be cornered by the term “eccentric,” crafting in her eighties some of the strangest stories ever to appear in The New Yorker—she’s one of the spine-stiffening writers. She makes a perfect quarantine companion. Someday, most likely, we will encounter life that is not as we know it. We might find it elsewhere in the universe, we might find it right here on Earth, or we might make it ourselves in a lab. Will we know it when we see it? “Life” isn’t a simple unified concept, but rather a collection of a number of life-like properties. I talk with astrobiologist Stuart Bartlett, who (in collaboration with

Someday, most likely, we will encounter life that is not as we know it. We might find it elsewhere in the universe, we might find it right here on Earth, or we might make it ourselves in a lab. Will we know it when we see it? “Life” isn’t a simple unified concept, but rather a collection of a number of life-like properties. I talk with astrobiologist Stuart Bartlett, who (in collaboration with  Conservatives once tried to legislate what went on in your bedroom; now it’s the left that obsesses over sexual codicils, not just for the bedroom but everywhere. Right-wingers from time to time made headlines campaigning against everything from The Last Temptation of Christ to “Fuck the Police,” though we laughed at the idea that Ice Cube made cops literally unsafe, and it was understood an artist had to do something fairly ambitious, like piss on a crucifix in public, to get conservative protesters off their couches.

Conservatives once tried to legislate what went on in your bedroom; now it’s the left that obsesses over sexual codicils, not just for the bedroom but everywhere. Right-wingers from time to time made headlines campaigning against everything from The Last Temptation of Christ to “Fuck the Police,” though we laughed at the idea that Ice Cube made cops literally unsafe, and it was understood an artist had to do something fairly ambitious, like piss on a crucifix in public, to get conservative protesters off their couches. In the Lateness of the World

In the Lateness of the World Anocha Suwichakornpong’s second feature-length film, By the Time it Gets Dark, is ostensibly a story about the brutal crackdown on student demonstrators at Thammasat University in Bangkok in 1976—the year of the filmmaker’s birth, forty years before the film was released—but its unpredictable, twisting narrative doubles back on itself in such strange ways that it becomes an interrogation of collective memory, a questioning of the role of history in contemporary Southeast Asia. The premise appears simple: two women arrive at an isolated house in the countryside, relieved to be there yet not entirely at ease with each other as they admire the spectacular views of the dry northern landscape. They have the clothes and demeanor of Bangkok dwellers, and we soon learn that they are there to tell the story of the Thammasat University killings. Taew, the older woman, was a leading figure in the student protests of the time, and has since become a celebrated writer. Ann, the younger, is a filmmaker, and spends the following days organizing oddly formal interviews with Taew, recorded on her camera, trying to piece together enough information to write a screenplay for a film based on the killings.

Anocha Suwichakornpong’s second feature-length film, By the Time it Gets Dark, is ostensibly a story about the brutal crackdown on student demonstrators at Thammasat University in Bangkok in 1976—the year of the filmmaker’s birth, forty years before the film was released—but its unpredictable, twisting narrative doubles back on itself in such strange ways that it becomes an interrogation of collective memory, a questioning of the role of history in contemporary Southeast Asia. The premise appears simple: two women arrive at an isolated house in the countryside, relieved to be there yet not entirely at ease with each other as they admire the spectacular views of the dry northern landscape. They have the clothes and demeanor of Bangkok dwellers, and we soon learn that they are there to tell the story of the Thammasat University killings. Taew, the older woman, was a leading figure in the student protests of the time, and has since become a celebrated writer. Ann, the younger, is a filmmaker, and spends the following days organizing oddly formal interviews with Taew, recorded on her camera, trying to piece together enough information to write a screenplay for a film based on the killings. The other day I caught myself reminiscing about high school with a kind of sadness and longing that can only be described as nostalgia. I felt imbued with a sense of wanting to go back in time and re-experience my classroom, the gym, the long hallways. Such bouts of nostalgia are all too common, but this case was striking because there is something I know for sure: I hated high school. I used to have nightmares, right before graduation, about having to redo it all, and would wake up in sweat and agony. I would never, ever like to go back to high school. So why did I feel nostalgia about a period I wouldn’t like to relive? The answer, as it turns out, requires we rethink our traditional idea of nostalgia.

The other day I caught myself reminiscing about high school with a kind of sadness and longing that can only be described as nostalgia. I felt imbued with a sense of wanting to go back in time and re-experience my classroom, the gym, the long hallways. Such bouts of nostalgia are all too common, but this case was striking because there is something I know for sure: I hated high school. I used to have nightmares, right before graduation, about having to redo it all, and would wake up in sweat and agony. I would never, ever like to go back to high school. So why did I feel nostalgia about a period I wouldn’t like to relive? The answer, as it turns out, requires we rethink our traditional idea of nostalgia. The timing couldn’t have been worse. In March, just as Thailand’s coronavirus outbreak began to ramp up, three hospitals in Bangkok announced that they had suspended testing for the virus because they had run out of reagents. Thai researchers rushed to help the country’s clinical laboratories meet the demand. Looking for affordable and easy-to-use tests, systems biologist Chayasith (Tao) Uttamapinant at the Vidyasirimedhi Institute of Science and Technology in Rayong reached out to an old acquaintance: CRISPR co-discoverer Feng Zhang, who had been developing an assay for the coronavirus inspired by the gene-editing technology.

The timing couldn’t have been worse. In March, just as Thailand’s coronavirus outbreak began to ramp up, three hospitals in Bangkok announced that they had suspended testing for the virus because they had run out of reagents. Thai researchers rushed to help the country’s clinical laboratories meet the demand. Looking for affordable and easy-to-use tests, systems biologist Chayasith (Tao) Uttamapinant at the Vidyasirimedhi Institute of Science and Technology in Rayong reached out to an old acquaintance: CRISPR co-discoverer Feng Zhang, who had been developing an assay for the coronavirus inspired by the gene-editing technology. An unconquerable anger has gripped the democratic world. The public seethes with feelings of grievance and seems ready to wreak havoc at any provocation. The spasm of fury that swept the United States after the death of George Floyd cost 19 additional lives and

An unconquerable anger has gripped the democratic world. The public seethes with feelings of grievance and seems ready to wreak havoc at any provocation. The spasm of fury that swept the United States after the death of George Floyd cost 19 additional lives and  There it floated, a luminous orange doughnut, glowing and fuzzy-edged, against a sea of darkness (Figure 1, below). Had it arrived without headline or caption, the world’s first ever image of a black hole might not have been recognised. Relayed across global news media, in April 2019, with appropriate fanfare and explanation, it caused the kind of stir you might expect of a scientific breakthrough. Prior to this, black holes had been ‘seen’ with the eye only through the images of science fiction. But now that we had a visual fix on black holes, an entity known only through abstract theory and via its gravitational effects on other bodies, were we any the wiser about them?

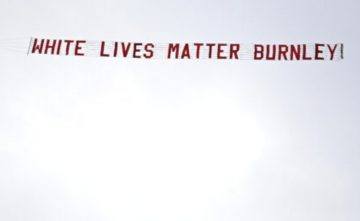

There it floated, a luminous orange doughnut, glowing and fuzzy-edged, against a sea of darkness (Figure 1, below). Had it arrived without headline or caption, the world’s first ever image of a black hole might not have been recognised. Relayed across global news media, in April 2019, with appropriate fanfare and explanation, it caused the kind of stir you might expect of a scientific breakthrough. Prior to this, black holes had been ‘seen’ with the eye only through the images of science fiction. But now that we had a visual fix on black holes, an entity known only through abstract theory and via its gravitational effects on other bodies, were we any the wiser about them? “White Lives Matter Burnley!” ran the banner trailed by a plane above the Etihad stadium, Manchester City’s ground, during a match with Burnley in June. Since the Premier League resumed after the coronavirus hiatus, players and officials have “taken the knee” at the start of matches in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement against racism and police brutality.

“White Lives Matter Burnley!” ran the banner trailed by a plane above the Etihad stadium, Manchester City’s ground, during a match with Burnley in June. Since the Premier League resumed after the coronavirus hiatus, players and officials have “taken the knee” at the start of matches in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement against racism and police brutality.