Elizabeth Nelson in The Ringer:

As late as 1999, Anthony Bourdain’s principal vocation remained his position as executive chef at the venerable but self-consciously middle-brow steak-frites joint Les Halles, on Park Avenue between 28th and 29th streets in Manhattan. Always a blessing and a curse, Bourdain’s restless mind continuously kicked the tires on other career avenues—Random House had published his Elmore Leonard–style culinary crime novel Bone in the Throat a few years previous—but by no means was he walking away from his calling in the kitchen. He was 43 years old, rode hard and put up wet, a recovering addict with a number of debts and a penchant for finding trouble in failing restaurants across the city. At Les Halles—at last—he had found sustained success and something resembling stability. This is what Anthony Bourdain would have had us believe.

As late as 1999, Anthony Bourdain’s principal vocation remained his position as executive chef at the venerable but self-consciously middle-brow steak-frites joint Les Halles, on Park Avenue between 28th and 29th streets in Manhattan. Always a blessing and a curse, Bourdain’s restless mind continuously kicked the tires on other career avenues—Random House had published his Elmore Leonard–style culinary crime novel Bone in the Throat a few years previous—but by no means was he walking away from his calling in the kitchen. He was 43 years old, rode hard and put up wet, a recovering addict with a number of debts and a penchant for finding trouble in failing restaurants across the city. At Les Halles—at last—he had found sustained success and something resembling stability. This is what Anthony Bourdain would have had us believe.

But in the spring of 2000, his sublimated literary ambitions suddenly caught up with and then quickly surpassed his cooking. Brought forth by the boutique publishing house Ecco Press, Bourdain’s long-gestating, industry-disrupting, love-letter-cum-horror-show-confessional Kitchen Confidential became an immediate sensation.

More here.

Jonathan Kirschner in Boston Review:

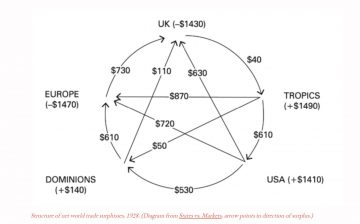

Jonathan Kirschner in Boston Review: Herman Mark Schwartz in Phenomenal World:

Herman Mark Schwartz in Phenomenal World: John Altmann and Bryan W. Van Norden in the NYT:

John Altmann and Bryan W. Van Norden in the NYT: Faisal Devji reviews Judith Butler’s The Force of Nonviolence, in the LA Review of Books:

Faisal Devji reviews Judith Butler’s The Force of Nonviolence, in the LA Review of Books: John Robert Lewis was born in 1940 near the Black Belt town of Troy, Alabama. His parents were sharecroppers, and he grew up spending Sundays with a great-grandfather who was born into slavery, and hearing about the lynchings of Black men and women that were still a commonplace in the region. When Lewis was a few months old, the manager of a chicken farm named Jesse Thornton was lynched about twenty miles down the road, in the town of Luverne. His offense was referring to a police officer by his first name, not as “Mister.” A mob pursued Thornton, stoned and shot him, then dumped his body in a swamp; it was found, a week later, surrounded by vultures.

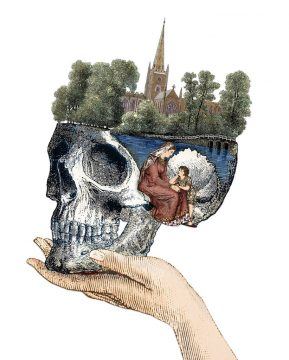

John Robert Lewis was born in 1940 near the Black Belt town of Troy, Alabama. His parents were sharecroppers, and he grew up spending Sundays with a great-grandfather who was born into slavery, and hearing about the lynchings of Black men and women that were still a commonplace in the region. When Lewis was a few months old, the manager of a chicken farm named Jesse Thornton was lynched about twenty miles down the road, in the town of Luverne. His offense was referring to a police officer by his first name, not as “Mister.” A mob pursued Thornton, stoned and shot him, then dumped his body in a swamp; it was found, a week later, surrounded by vultures. “Hamnet” is an exploration of marriage and grief written into the silent opacities of a life that is at once extremely famous and profoundly obscure. Countless scholars have combed through Elizabethan England’s parish and court records looking for traces of William Shakespeare. But what we know for sure, if set down unvarnished by learned and often fascinating speculation, would barely make a slender monograph. As William Styron once wrote, the historical novelist works best when fed on short rations. The rations at Maggie O’Farrell’s disposal are scant but tasty, just the kind of morsels to nourish an empathetic imagination. We know, for instance, that at the age of 18, Shakespeare married a woman named Anne or Agnes Hathaway, who was 26 and three months pregnant. (That condition wasn’t unusual for the time: Studies of marriage and baptism records reveal that as many as one-third of brides went to the altar pregnant.) Hathaway was the orphaned daughter of a farmer near Stratford-upon-Avon who had bequeathed her a dowry. This status gave her more latitude than many women of her time, who relied on paternal permission in choosing a mate.

“Hamnet” is an exploration of marriage and grief written into the silent opacities of a life that is at once extremely famous and profoundly obscure. Countless scholars have combed through Elizabethan England’s parish and court records looking for traces of William Shakespeare. But what we know for sure, if set down unvarnished by learned and often fascinating speculation, would barely make a slender monograph. As William Styron once wrote, the historical novelist works best when fed on short rations. The rations at Maggie O’Farrell’s disposal are scant but tasty, just the kind of morsels to nourish an empathetic imagination. We know, for instance, that at the age of 18, Shakespeare married a woman named Anne or Agnes Hathaway, who was 26 and three months pregnant. (That condition wasn’t unusual for the time: Studies of marriage and baptism records reveal that as many as one-third of brides went to the altar pregnant.) Hathaway was the orphaned daughter of a farmer near Stratford-upon-Avon who had bequeathed her a dowry. This status gave her more latitude than many women of her time, who relied on paternal permission in choosing a mate. One night in August 2005, just after I’d moved to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, for a job as a theology professor, I needed beer. To get to the distributor, I drove over a concrete bridge, its four pylons etched with words like “Perseverance” and “Industry” and topped by monumental eagles. Once there, I wandered through the pallets of warm cases trying to find a thirty-pack of PBR until the thin, gruff man behind the counter asked what I was looking for. I told him, he pointed to the right pallet, and I met him at the register.

One night in August 2005, just after I’d moved to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, for a job as a theology professor, I needed beer. To get to the distributor, I drove over a concrete bridge, its four pylons etched with words like “Perseverance” and “Industry” and topped by monumental eagles. Once there, I wandered through the pallets of warm cases trying to find a thirty-pack of PBR until the thin, gruff man behind the counter asked what I was looking for. I told him, he pointed to the right pallet, and I met him at the register. Seven years ago

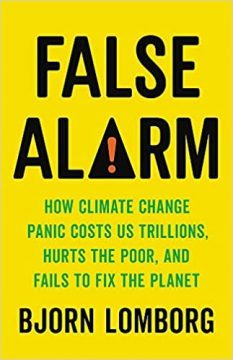

Seven years ago The thesis of Bjorn Lomborg’s “False Alarm” is simple and simplistic: Activists have been sounding a false alarm about the dangers of climate change. If we listen to them, Lomborg says, we will waste trillions of dollars, achieve little and the poor will suffer the most. Science has provided a way to carefully balance costs and benefits, if we would only listen to its clarion call. And, of course, the villain in this “false alarm,” the boogeyman for all of society’s ills, is the hyperventilating media. Lomborg doesn’t use the term “fake news,” but it’s there if you read between the lines.

The thesis of Bjorn Lomborg’s “False Alarm” is simple and simplistic: Activists have been sounding a false alarm about the dangers of climate change. If we listen to them, Lomborg says, we will waste trillions of dollars, achieve little and the poor will suffer the most. Science has provided a way to carefully balance costs and benefits, if we would only listen to its clarion call. And, of course, the villain in this “false alarm,” the boogeyman for all of society’s ills, is the hyperventilating media. Lomborg doesn’t use the term “fake news,” but it’s there if you read between the lines. T

T This isn’t a style of the Church, Italy, a patron, or a doctrine. It’s a personal style, the work of a self-taught 40-something gay man who devised ways to dye one’s hair blond as well as build bridges. Art history has been going through regular stylistic shifts ever since. This is what a social revolution looks like.

This isn’t a style of the Church, Italy, a patron, or a doctrine. It’s a personal style, the work of a self-taught 40-something gay man who devised ways to dye one’s hair blond as well as build bridges. Art history has been going through regular stylistic shifts ever since. This is what a social revolution looks like.