Category: Recommended Reading

On ‘My Morningless Mornings’

Pete Tosiello at Full Stop:

Even when ruminating upon dream diaries, werewolves, and vampires, Golberg’s erudition imbues her childlike wonder with a preacher’s certitude. She finds analogies across cultures and languages, weaving centuries-old philosophies into her personal examination of late-night gloom and early-morning revelation. There’s a selective nature to her surveys, some of which take the form of art and literary criticism. But the essays build upon successive themes, Golberg’s metaphors compounding and accreting into a more solid, ambitious exploration of identity. Who are we, these essays ask, and when are we most ourselves? “I suppose this was Jung’s point all along, that the dreamworld is not separate from the everyday world,” she considers, “that we enact our dreams in daily life as we enact our daily life in dreams, and that to divide these parts of ourselves — the sleeping self and the wide-awake self — makes us incomplete.” These analyses make approachable essays even for readers not steeped in the work of Japanese novelists and nineteenth-century painters.

Even when ruminating upon dream diaries, werewolves, and vampires, Golberg’s erudition imbues her childlike wonder with a preacher’s certitude. She finds analogies across cultures and languages, weaving centuries-old philosophies into her personal examination of late-night gloom and early-morning revelation. There’s a selective nature to her surveys, some of which take the form of art and literary criticism. But the essays build upon successive themes, Golberg’s metaphors compounding and accreting into a more solid, ambitious exploration of identity. Who are we, these essays ask, and when are we most ourselves? “I suppose this was Jung’s point all along, that the dreamworld is not separate from the everyday world,” she considers, “that we enact our dreams in daily life as we enact our daily life in dreams, and that to divide these parts of ourselves — the sleeping self and the wide-awake self — makes us incomplete.” These analyses make approachable essays even for readers not steeped in the work of Japanese novelists and nineteenth-century painters.

more here.

The Poetry of Eavan Boland

Theo Dorgan at the Dublin Review of Books:

Steadily, poem by poem and book by book, Eavan worked her way into the heart of darkness, not in the Conradian sense of course, but into the centre of those marginal, penumbral zones outside the spotlight of what was “officially” deemed worthy of being remembered. Hers was a double journey ‑ the poet finding her way into the self-granted warrant of her craft, the citizen struggling for the vindication of women, for a more amplified and more truthful narrative of Ireland. Her method was her purpose: in confronting exclusion, in the historical sense, she simultaneously chose to examine her own path into permission, into the poem, ever-present to herself, always questioning her step-by-step progress into her own gathering experience of making. And at the same time, not as a polemicist but as a citizen, she was attempting to formulate, or reformulate, a more ample and truthful vision of Ireland. By the time she had arrived at the pared back landscapes and poemscapes of Outside History and Against Love Poetry, it seems to me that she had succeeded in fusing her double quest: she had found a way to speak plainly of and for all those whom history had cast aside, a neglect, often deliberate, that was both political and moral; and at the same time she had found in herself a voice she could finally consider adequate to her subject and to the unforgiving demands of her craft.

Steadily, poem by poem and book by book, Eavan worked her way into the heart of darkness, not in the Conradian sense of course, but into the centre of those marginal, penumbral zones outside the spotlight of what was “officially” deemed worthy of being remembered. Hers was a double journey ‑ the poet finding her way into the self-granted warrant of her craft, the citizen struggling for the vindication of women, for a more amplified and more truthful narrative of Ireland. Her method was her purpose: in confronting exclusion, in the historical sense, she simultaneously chose to examine her own path into permission, into the poem, ever-present to herself, always questioning her step-by-step progress into her own gathering experience of making. And at the same time, not as a polemicist but as a citizen, she was attempting to formulate, or reformulate, a more ample and truthful vision of Ireland. By the time she had arrived at the pared back landscapes and poemscapes of Outside History and Against Love Poetry, it seems to me that she had succeeded in fusing her double quest: she had found a way to speak plainly of and for all those whom history had cast aside, a neglect, often deliberate, that was both political and moral; and at the same time she had found in herself a voice she could finally consider adequate to her subject and to the unforgiving demands of her craft.

more here.

Eavan Boland at Cornell

When Evolution Is Infectious: How “probiotic epidemics” help wildlife—and us—survive

Moises Velasquez-Manoff in Nautilus:

Ever since Charles Darwin taught us that life is constantly driven to change by myriad pressures—that species are not static, but are constantly morphing—biologists have debated how fast those changes can occur. The discovery of the genome a century after Darwin published On the Origin of Species seemed to demarcate an upper limit. Animals could evolve only as fast as advantageous genes could arise and spread, and as existing genomes could be reshuffled through sexual reproduction. But then came “epigenetics”: Some adaptation could occur more quickly, without changing genes themselves, but by altering how existing genes translated into living flesh. Rosenberg and others are proposing an even quicker process—organisms can adapt rapidly by switching their symbiotic microbes. The very quality that makes pandemics so terrifying—rapid contagion—may also drive mass adaptation.

Ever since Charles Darwin taught us that life is constantly driven to change by myriad pressures—that species are not static, but are constantly morphing—biologists have debated how fast those changes can occur. The discovery of the genome a century after Darwin published On the Origin of Species seemed to demarcate an upper limit. Animals could evolve only as fast as advantageous genes could arise and spread, and as existing genomes could be reshuffled through sexual reproduction. But then came “epigenetics”: Some adaptation could occur more quickly, without changing genes themselves, but by altering how existing genes translated into living flesh. Rosenberg and others are proposing an even quicker process—organisms can adapt rapidly by switching their symbiotic microbes. The very quality that makes pandemics so terrifying—rapid contagion—may also drive mass adaptation.

To support the hologenome theory, Rosenberg and others look to the study of the human microbiome, particularly the example of Clostridium difficile. People tend to acquire the bacterium during hospital stays and after they’ve “clearcut” their native microbes with antibiotics directed at another infection. C. difficile then blooms. Patients can end up delirious and in pain, weakened by an unremitting torrent of bloody diarrhea. The microbe infects an estimated 500,000 Americans yearly, killing some 29,000 of them within a month.

C. difficile is increasingly resistant to antibiotics, so further treatment fails in about 1 in 5 cases. For this subset, the “fecal transplant” is nearly miraculous. The procedure involves “implanting” stool from a healthy person, via enema, or in pills, into the intestines of one stricken with C. difficile. And it’s 94 percent effective at curing C. difficile. It works, scientists think, by restoring a fully functioning microbial ecosystem in one fell swoop. The donor’s tight-knit community deprives the pathogen C. difficile of an ecological niche, squeezing it from the gut. Technically, stool transplants are not “probiotic epidemics.” But the principle the transplant illustrates—that native microbes prevent disease, and that tweaking those microbes can fend off a deadly infection—is precisely what scientists think could drive a probiotic epidemic.

More here.

Pioneers of revolutionary CRISPR gene editing win chemistry Nobel

Callaway and Ledford in Nature:

It’s CRISPR. Two scientists who pioneered the revolutionary gene-editing technology are the winners of this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The Nobel Committee’s selection of Emmanuelle Charpentier, now at the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens in Berlin, and Jennifer Doudna, at the University of California, Berkeley, puts to rest years of speculation as to who would be recognized for their work developing the CRISPR–Cas9 gene-editing tools. The technology has swept through labs worldwide and has countless applications: researchers hope to use it to alter human genes to eliminate diseases, create hardier plants, wipe out pathogens and more.

It’s CRISPR. Two scientists who pioneered the revolutionary gene-editing technology are the winners of this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The Nobel Committee’s selection of Emmanuelle Charpentier, now at the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens in Berlin, and Jennifer Doudna, at the University of California, Berkeley, puts to rest years of speculation as to who would be recognized for their work developing the CRISPR–Cas9 gene-editing tools. The technology has swept through labs worldwide and has countless applications: researchers hope to use it to alter human genes to eliminate diseases, create hardier plants, wipe out pathogens and more.

Several other scientists, in addition to Charpentier and Doudna, have been cited — and recognized in other high-profile awards — as key contributors in the development of CRISPR. They include Feng Zhang at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts, George Church at MIT and biochemist Virginijus Siksnys at Vilnius University in Lithuania. Doudna was “really sound asleep” when her buzzing phone woke her and she took a call from a Nature reporter, who broke the news. “I grew up in a small town in Hawaii and I never in a hundred million years would have imagined this happening,” says Doudna. “I’m really stunned, I’m just completely in shock.” “I know so many wonderful scientists who will never receive this, for reasons that have nothing to do with the fact that they are wonderful scientists,” Doudna says. “I am really kind of humbled.”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

The Precision

There is a modesty in nature. In the small

of it and in the strongest. The leaf moves

just the amount the breeze indicates

and nothing more. In the power of lust, too,

there can be a quiet and clarity, a fusion

of exact moments. There is a silence of it

inside the thundering. And when the body swoons,

it is because the heart knows its truth.

There is directness and equipoise in the fervor,

just as the greatest turmoil has precision.

Like the discretion a tornado has when it tears

down building after building, house by house.

It is enough, Kafka said, that the arrow fit

exactly into the wound that it makes. I think

about my body in love as I look down on these

lavish apple trees and the workers moving

with skill from one to the next, singing.

by Linda Gregg

from Things and Flesh

Graywolf Press, 1999

Tuesday, October 6, 2020

Jürgen Habermas: Germany’s second chance

Jürgen Habermas in Blätter:

Thirty years after the seismic shift in world history of 1989-90 with the collapse of communism, the sudden eruption of life-changing events could be another watershed. This will be decided in the next few months—in Brussels and in Berlin too.

Thirty years after the seismic shift in world history of 1989-90 with the collapse of communism, the sudden eruption of life-changing events could be another watershed. This will be decided in the next few months—in Brussels and in Berlin too.

At first glance it might seem a bit far-fetched to compare the overcoming of a world order divided into two opposing camps and the global spread of victorious capitalism with the elemental nature of a pandemic that caught us off-guard and the related global economic crisis happening on an unprecedented scale. Yet if we Europeans can find a constructive response to the shock, this might provide a parallel between the two world-shattering events.

In those days, German and European unification were linked as if joined at the hip. Today, any connection between these two processes, self-evident then, is not so obvious. Yet, while Germany’s national-day celebration (October 3rd) has remained curiously pallid during the last three decades, one might speculate along the following lines: imbalances within the German unification process are not the reason for the surprising revival of its European counterpart but the historical distance which we have now gained from those domestic problems has helped to make the federal government finally revert to the historic task it had put to one side—giving political shape and definition to Europe’s future.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Sean B. Carroll on Randomness and the Course of Evolution

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Evolution is a messy business, involving as it does selection pressures, mutations, genetic drift, and the effects of random external interventions. So in the end, how much of it is predictable, and how much is in the hands of chance? Today we’re thrilled to have as a guest my evil (but more respectable, by most measures) twin, the biologist Sean B. Carroll. Sean is both a leader of the modern evo-devo revolution, and a wonderful and diverse writer. We talk about the importance of randomness and unpredictability in life, from the evolution of species to the daily routine of every individual.

Evolution is a messy business, involving as it does selection pressures, mutations, genetic drift, and the effects of random external interventions. So in the end, how much of it is predictable, and how much is in the hands of chance? Today we’re thrilled to have as a guest my evil (but more respectable, by most measures) twin, the biologist Sean B. Carroll. Sean is both a leader of the modern evo-devo revolution, and a wonderful and diverse writer. We talk about the importance of randomness and unpredictability in life, from the evolution of species to the daily routine of every individual.

More here.

A Famous Misanthrope Shows His Heartwarming Side

Daphne Merkin at Bookforum:

Did Larkin’s parents fuck him up? According to his sister Catherine (“Kitty”), ten years his senior, both parents “worshipped” Philip. All the same, they have undoubtedly been demonized—sometimes by the poet himself. There were the sour references he made to his childhood in his poetry (“a forgotten boredom”), and then there was his adamantine bachelor’s decision not to marry, seemingly because he did not want to replicate what appears to have been an unhappy parental union. More damning facts have emerged since Larkin died in 1985 at the age of sixty-three, a much-admired and influential figure who had turned down the position of poet laureate a year earlier. These include his father Sydney’s blithe admiration for Nazi Germany, as evidenced by his observing on the first page of his twenty-volume diary (!!) that “those who had visited Germany were much impressed by the good government and order of the country as by the cleanliness and good behavior of the people,” as well as his unrepentant anti-Semitism. As for his mother Eva, Andrew Motion’s 1993 biography of Larkin describes her as “indispensable but infuriating,” like some grating housemaid. Larkin himself characterizes her in a letter to Monica Jones, the longest-running of his several lovers, as “nervy, cowardly, obsessional, boring, grumbling, irritating, self pitying” before going on to amend his portrait: “on the other hand, she’s kind, timid, unselfish, loving.”

Did Larkin’s parents fuck him up? According to his sister Catherine (“Kitty”), ten years his senior, both parents “worshipped” Philip. All the same, they have undoubtedly been demonized—sometimes by the poet himself. There were the sour references he made to his childhood in his poetry (“a forgotten boredom”), and then there was his adamantine bachelor’s decision not to marry, seemingly because he did not want to replicate what appears to have been an unhappy parental union. More damning facts have emerged since Larkin died in 1985 at the age of sixty-three, a much-admired and influential figure who had turned down the position of poet laureate a year earlier. These include his father Sydney’s blithe admiration for Nazi Germany, as evidenced by his observing on the first page of his twenty-volume diary (!!) that “those who had visited Germany were much impressed by the good government and order of the country as by the cleanliness and good behavior of the people,” as well as his unrepentant anti-Semitism. As for his mother Eva, Andrew Motion’s 1993 biography of Larkin describes her as “indispensable but infuriating,” like some grating housemaid. Larkin himself characterizes her in a letter to Monica Jones, the longest-running of his several lovers, as “nervy, cowardly, obsessional, boring, grumbling, irritating, self pitying” before going on to amend his portrait: “on the other hand, she’s kind, timid, unselfish, loving.”

more here.

Daphne Merkin In Conversation With Deborah Solomon

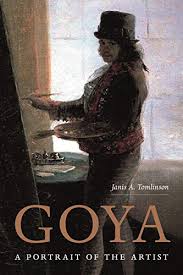

Goya: A Portrait of the Artist

Robin Simon at Literary Review:

Francisco Goya y Lucientes was a mass of contradictions. He was a liberal, initially sympathetic to the French Revolution, who liked nothing better than to go hunting with successive absolutist monarchs of Spain. He was deputy director of the Royal Academy in Madrid, yet believed that traditional academic training was useless, insisting that ‘there are no rules in Painting’ and the ‘servile obligation of making all study or follow the same path is a great impediment for the Young’.

Francisco Goya y Lucientes was a mass of contradictions. He was a liberal, initially sympathetic to the French Revolution, who liked nothing better than to go hunting with successive absolutist monarchs of Spain. He was deputy director of the Royal Academy in Madrid, yet believed that traditional academic training was useless, insisting that ‘there are no rules in Painting’ and the ‘servile obligation of making all study or follow the same path is a great impediment for the Young’.

Goya was by disposition anticlerical, though he happily executed countless religious images designed to satisfy Spanish Catholic worshippers. These paintings are, frankly, rather soupy. That is not what we expect from Goya, who is usually seen as more loopy than soupy: this is the man who created the ‘Black Paintings’, Los Sueños, The Disasters of War, The Third of May 1808 and Los Caprichos.

more here.

How Trump damaged science — and why it could take decades to recover

Jeff Tolefson in Nature:

People packed in by the thousands, many dressed in red, white and blue and carrying signs reading “Four more years” and “Make America Great Again”. They came out during a global pandemic to make a statement, and that’s precisely why they assembled shoulder-to-shoulder without masks in a windowless warehouse, creating an ideal environment for the coronavirus to spread. US President Donald Trump’s rally in Henderson, Nevada, on 13 September contravened state health rules, which limit public gatherings to 50 people and require proper social distancing. Trump knew it, and later flaunted the fact that the state authorities failed to stop him. Since the beginning of the pandemic, the president has behaved the same way and refused to follow basic health guidelines at the White House, which is now at the centre of an ongoing outbreak. As of 5 October, the president was in a hospital and was receiving experimental treatments.

People packed in by the thousands, many dressed in red, white and blue and carrying signs reading “Four more years” and “Make America Great Again”. They came out during a global pandemic to make a statement, and that’s precisely why they assembled shoulder-to-shoulder without masks in a windowless warehouse, creating an ideal environment for the coronavirus to spread. US President Donald Trump’s rally in Henderson, Nevada, on 13 September contravened state health rules, which limit public gatherings to 50 people and require proper social distancing. Trump knew it, and later flaunted the fact that the state authorities failed to stop him. Since the beginning of the pandemic, the president has behaved the same way and refused to follow basic health guidelines at the White House, which is now at the centre of an ongoing outbreak. As of 5 October, the president was in a hospital and was receiving experimental treatments.

Trump’s actions — and those of his staff and supporters — should come as no surprise. Over the past eight months, the president of the United States has lied about the dangers posed by the coronavirus and undermined efforts to contain it; he even admitted in an interview to purposefully misrepresenting the viral threat early in the pandemic. Trump has belittled masks and social-distancing requirements while encouraging people to protest against lockdown rules aimed at stopping disease transmission. His administration has undermined, suppressed and censored government scientists working to study the virus and reduce its harm. And his appointees have made political tools out of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), ordering the agencies to put out inaccurate information, issue ill-advised health guidance, and tout unproven and potentially harmful treatments for COVID-19.

“This is not just ineptitude, it’s sabotage,” says Jeffrey Shaman, an epidemiologist at Columbia University in New York City, who has modelled the evolution of the pandemic and how earlier interventions might have saved lives in the United States. “He has sabotaged efforts to keep people safe.”

More here.

Wish a President Well Who Doesn’t Wish You Well

Bret Stephen in The New York Times:

“Any mans death diminishes me,” wrote John Donne, “because I am involved in Mankinde.” With that thought, let us all wish Donald Trump a full and speedy recovery from his bout of Covid-19. We wish him well because, even, or especially, in our hyperpolitical age, some things must be beyond politics. When everything is political, nothing is sacred — starting with human life. It’s a point the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century understood well.

“Any mans death diminishes me,” wrote John Donne, “because I am involved in Mankinde.” With that thought, let us all wish Donald Trump a full and speedy recovery from his bout of Covid-19. We wish him well because, even, or especially, in our hyperpolitical age, some things must be beyond politics. When everything is political, nothing is sacred — starting with human life. It’s a point the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century understood well.

…We wish him well because we are better than he is. We are better than the man who mocked Hunter Biden for his substance-abuse issues. We are better than the man who called NeverTrumpers “human scum.” We are better than the man who wants to put his political opponents in jail. We are better than the man who publicly humiliates his own advisers. We are better than the man who demeaned the gold-star parents of a fallen soldier. We are better than the man who pantomimed the physical disabilities of a reporter. We are better than the man who stiffs his suppliers and swindles his “students.” We are better than the man who uses his celebrity to grope. We are better than the man who took a bone-spur draft deferment so that he could live to denigrate the courage of prisoners of war. We are better than the man who race-baited and conspiracy-theorized his way into political relevance.

We wish him well because it’s the right thing to do. It’s more than reason enough.

More here.

Nobel Prize in Physics awarded for black hole discoveries to Roger Penrose, Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez

Emma Reynolds and Katie Hunt at CNN:

The 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics has been awarded to scientists Roger Penrose, Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez for their discoveries about black holes.

The 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics has been awarded to scientists Roger Penrose, Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez for their discoveries about black holes.

Göran K. Hansson, secretary for the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, said at Tuesday’s ceremony in Stockholm that this year’s prize was about “the darkest secrets of universe.”

Penrose, a professor at the University of Oxford who worked with Stephen Hawking, was awarded half of the prize “for the discovery that black hole formation is a robust prediction of the general theory of relativity.” The other half was awarded jointly to Genzel and Ghez “for the discovery of a supermassive compact object at the center of our galaxy.”

“Penrose, Genzel and Ghez together showed us that black holes are awe-inspiring, mathematically sublime, and actually exist,” Tom McLeish, professor of natural philosophy at the University of York, told the Science Media Centre in London.

More here.

In May, Sabine Hossenfelder explained why Roger Penrose should win the physics Nobel prize, and today he has

Tuesday Poem

Self-Portrait as Pop Culture Reference

I was born in 1993, the year Regie Cabico became the first

Asian American to win the Nuyorican Poets Cafe Grand Slam.

I want these facts to mean something to each other,

the way a room is just a room until love or its inverse

tells me what to do with the person standing in it.

Once, I stood on a street corner & a white woman, stunned

by the horizon I passed through to be here, put her hands

on my face to relearn history. I was named after a movie star

who died by drowning, A Streetcar Named Desire gone now

to water, & split an ocean every year to see my mother again.

The first man I loved named me after a dead American

& crushed childhood into a flock of hands.

The women I loved taught me that water cures anything

that ails, given enough thirst. I speak thirst,

sharpen the tongue that slithered through continents

& taught my ancestors to pray its name. I pray its name

& so undertake the undertaker, it preys my Mandarin name

so I watch Chinese dramas with bright-eyed bodies

to forestall forgetting my own. I’ve watched my skin

turned fragrant ornament thrown over women

the colour of surrender & they were praised for wearing it.

I wake wearing my skin & praise myself for waking.

My skin, this well-worn hide I fold into a boat

sturdy enough to bisect any body of water,

was made from light breaking through my mother’s hands–

my mother lifting her fingers to the sky & inventing

a story where she touched & swallowed it whole.

I’ve swallowed every name I was given

to spit them back better. To write is to cradle memory

& creation myth both & emerge with the fact

of your hands. I praise the first book

that touched me because it was beautiful,

because it was written by a stranger born looking

just a little like me & that made him beautiful, & in it

I find every person I’ve loved into godhood,

tunneling through the page & beyond the echo

of those beloved trees allowing breath: their shadows

blurring into a wave, rich & urgent, to greet me.

by Natalie Wee

from Split This Rock

Listen as Natalie Wee reads “Self-Portrait as Pop Culture Reference.”

Sunday, October 4, 2020

Pathologizing Desire: Current contempt for age gap relationships serves to strip both men and women of their agency

Jessa Crispin in the Boston Review:

The older man coupled with the younger woman is Hollywood tradition, from a young Audrey Hepburn pursued by Cary Grant (Charade), Fred Astaire (Funny Face), or Humphrey Bogart (Sabrina) (all of the men looking overripe and easily bruised at the time of filming), to Catherine Zeta-Jones writhing in front of Sean Connery in Entrapment, or marrying her real life partner Michael Douglas, twenty-five years her elder. This age gap coupling is also a reality; around 30 percent of American heterosexual marriages consist of men at least four years older than their partners.

The older man coupled with the younger woman is Hollywood tradition, from a young Audrey Hepburn pursued by Cary Grant (Charade), Fred Astaire (Funny Face), or Humphrey Bogart (Sabrina) (all of the men looking overripe and easily bruised at the time of filming), to Catherine Zeta-Jones writhing in front of Sean Connery in Entrapment, or marrying her real life partner Michael Douglas, twenty-five years her elder. This age gap coupling is also a reality; around 30 percent of American heterosexual marriages consist of men at least four years older than their partners.

Yet conversations around film—from the unfairness of the way women “age out” of roles, disappearing from our screens once they hit middle age, to the new belief that film should provide moral instruction and depict life as it should be rather than how it is—have problematized the age gap in heterosexual couples. Owing to this new taboo, both real couples and fictional couples that display these age gaps are roundly lambasted on social media.

More here.

A Visit To The Most Important Survey Telescope Ever Built

Bruce Dorminey in Forbes:

Riding through the northern Chilean Andes, an incredibly rugged swath of desert that I’m sure in times gone by has tried men’s souls —- no one would ever suspect they were about to enter a prime ground-based window onto the Universe. It’s hardly the kind of landscape that evokes oohs and aahs for its beauty. But this dust-ridden land is home to some of the world’s greatest observatories. And by night, it offers an aperture onto the center of our own Milky Way and far-flung galaxies that literally stretch back to the beginning of time.

Riding through the northern Chilean Andes, an incredibly rugged swath of desert that I’m sure in times gone by has tried men’s souls —- no one would ever suspect they were about to enter a prime ground-based window onto the Universe. It’s hardly the kind of landscape that evokes oohs and aahs for its beauty. But this dust-ridden land is home to some of the world’s greatest observatories. And by night, it offers an aperture onto the center of our own Milky Way and far-flung galaxies that literally stretch back to the beginning of time.

My driver and I, however, are headed to the $473 million Vera Rubin Observatory, formerly known as the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST), which has been under construction since 2014. This 8.4 meter extremely wide-field telescope is completely unprecedented, never before possible and never before attempted.

In just its first year of operation, the LSST organization says that the telescope will see more asteroids, stars, quasars, and galaxies and issue more alerts than all previous telescopes combined.

More here.

The definitive case for ending the filibuster

Ezra Klein in Vox:

If Joe Biden wins the White House, and Democrats take back the Senate, there is one decision that will loom over every other. It is a question that dominated no debates and received only glancing discussion across the campaign, and yet it is the master choice that will either unlock their agenda or ensure they fail to deliver on their promises.

If Joe Biden wins the White House, and Democrats take back the Senate, there is one decision that will loom over every other. It is a question that dominated no debates and received only glancing discussion across the campaign, and yet it is the master choice that will either unlock their agenda or ensure they fail to deliver on their promises.

That decision? Whether the requirement for passing a bill through the Senate should be 60 votes or 51 votes. Whether, in other words, to eliminate the modern filibuster, and make governance possible again.

Virtually everything Democrats have sworn to do — honoring John Lewis’s legacy by strengthening the right to vote, preserving the climate for future generations by decarbonizing America, ensuring no gun is sold without a background check, raising the minimum wage, implementing universal pre-K, ending dark money in politics, guaranteeing paid family leave, offering statehood to Washington, DC, and Puerto Rico, reinvigorating unions, passing the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act — hinges on this question.

More here.