Rebecca Bengal at The Paris Review:

In 1976, twenty-five-year-old Wendy Ewald rented a small house on Ingram Creek in a remote landscape in eastern Kentucky, hoping to make a photographic document of “the soul and rhythm of the place.” As she writes in an essay included in the expanded new edition of Portraits and Dreams: Photographs and Stories By Children of The Appalachians, originally published in 1985, her camera landed on the “commonplaces” of Letcher County. Set in the Cumberland Mountains at the edge of Kentucky and Virginia, Lechter Country is in the rural, rolling, rugged, coal-mining heart of the still sprawling and still vastly misunderstood and frequently mispronounced region known as Appalachia (the correct pronunciation is Appa-LATCH-uh). More than a decade before Ewald’s arrival, the publication of Night Comes to the Cumberlands: A Biography of a Depressed Area, by local lawyer and environmental crusader Harry Caudill, had helped spur John F. Kennedy and later Lyndon B. Johnson to declare war on poverty in Letcher County and regions like it. But Ewald did not intend to photograph “poverty,” or to photograph the place in the reductive way it had come to be depicted. She was interested in the way the people pictured themselves.

In 1976, twenty-five-year-old Wendy Ewald rented a small house on Ingram Creek in a remote landscape in eastern Kentucky, hoping to make a photographic document of “the soul and rhythm of the place.” As she writes in an essay included in the expanded new edition of Portraits and Dreams: Photographs and Stories By Children of The Appalachians, originally published in 1985, her camera landed on the “commonplaces” of Letcher County. Set in the Cumberland Mountains at the edge of Kentucky and Virginia, Lechter Country is in the rural, rolling, rugged, coal-mining heart of the still sprawling and still vastly misunderstood and frequently mispronounced region known as Appalachia (the correct pronunciation is Appa-LATCH-uh). More than a decade before Ewald’s arrival, the publication of Night Comes to the Cumberlands: A Biography of a Depressed Area, by local lawyer and environmental crusader Harry Caudill, had helped spur John F. Kennedy and later Lyndon B. Johnson to declare war on poverty in Letcher County and regions like it. But Ewald did not intend to photograph “poverty,” or to photograph the place in the reductive way it had come to be depicted. She was interested in the way the people pictured themselves.

more here.

Declan Walsh begins his captivating new book on Pakistan with an account of how he came to leave the country for the first time, abruptly and involuntarily in May 2013. “The angels came to spirit me away,” is the way he puts it, using the Urdu slang for the all-powerful men of the

Declan Walsh begins his captivating new book on Pakistan with an account of how he came to leave the country for the first time, abruptly and involuntarily in May 2013. “The angels came to spirit me away,” is the way he puts it, using the Urdu slang for the all-powerful men of the  In Stanford in 2008, the Irish poet Eavan Boland told me how much she admired the work of

In Stanford in 2008, the Irish poet Eavan Boland told me how much she admired the work of  Since Nature’s earliest issues, we have been publishing news, commentary and primary research on science and politics. But why does a journal of science need to cover politics? It’s an important question that readers often ask.

Since Nature’s earliest issues, we have been publishing news, commentary and primary research on science and politics. But why does a journal of science need to cover politics? It’s an important question that readers often ask. AC: I need to rephrase this question slightly in order to answer it. “Moral realism” is a label that I deliberately don’t use in describing my image of ethics. Not that, abstractly considered, the term is obviously ill-suited to capture things I believe. It is, for instance, a conviction of mine that that there are morally salient aspects of the world that as such lend themselves to empirical discovery. A case could easily be made for speaking of moral realism in this connection. But that would likely generate confusion. When I claim that, say, humans and animals have moral qualities that are as such observable, I work with an understanding of what the world is like, and of what is involved in knowing it, that is foreign to familiar discussions of moral realism. These discussions are often structured by the assumption that objectivity excludes anything that is only adequately conceivable in terms of reference to human subjectivity. Moral realism is frequently envisioned as an improbable position on which moral values are objective in this subjectivity-extruding sense while still somehow having a direct bearing on action and choice. Thus does the specter of Mackie’s “argument from queerness” still haunt the halls of moral philosophy.

AC: I need to rephrase this question slightly in order to answer it. “Moral realism” is a label that I deliberately don’t use in describing my image of ethics. Not that, abstractly considered, the term is obviously ill-suited to capture things I believe. It is, for instance, a conviction of mine that that there are morally salient aspects of the world that as such lend themselves to empirical discovery. A case could easily be made for speaking of moral realism in this connection. But that would likely generate confusion. When I claim that, say, humans and animals have moral qualities that are as such observable, I work with an understanding of what the world is like, and of what is involved in knowing it, that is foreign to familiar discussions of moral realism. These discussions are often structured by the assumption that objectivity excludes anything that is only adequately conceivable in terms of reference to human subjectivity. Moral realism is frequently envisioned as an improbable position on which moral values are objective in this subjectivity-extruding sense while still somehow having a direct bearing on action and choice. Thus does the specter of Mackie’s “argument from queerness” still haunt the halls of moral philosophy. India first started using pellet-firing shotguns against Kashmiris in 2010 but the matter only hit international prominence in 2016 when protests following the death of Burhan Wani resulted in thousands of injuries, the blinding of hundreds and the deaths of over 70 people.

India first started using pellet-firing shotguns against Kashmiris in 2010 but the matter only hit international prominence in 2016 when protests following the death of Burhan Wani resulted in thousands of injuries, the blinding of hundreds and the deaths of over 70 people. Twenty-five years after he and his parents fled Ukraine, Ilya Kaminsky went back to Odessa, the city of his childhood. As he explored the city, he did not feel that he had truly returned until he removed his hearing aids. He has written that, for him, Odessa is ‘a silent city, where the language is invisibly linked to my father’s lips moving as I watch his mouth repeat stories again and again. He turns away. The story stops.’

Twenty-five years after he and his parents fled Ukraine, Ilya Kaminsky went back to Odessa, the city of his childhood. As he explored the city, he did not feel that he had truly returned until he removed his hearing aids. He has written that, for him, Odessa is ‘a silent city, where the language is invisibly linked to my father’s lips moving as I watch his mouth repeat stories again and again. He turns away. The story stops.’ There is a much darker side to his life, too. The relentless womanising, including with vulnerable people far, far younger than him; the children so numerous they were hard to keep track of; the brutal break-ups, vicious feuds and spasms of verbal cruelty that made Freud, for many people, an impossibly sulphurous figure, a coldly brilliant predator smoking with menace. Observing him at the Jewish wedding in London of the painter RB Kitaj, the poet Stephen Spender whispered to Feaver: “I can’t stand being in the same place with Lucian. He is an evil man.”

There is a much darker side to his life, too. The relentless womanising, including with vulnerable people far, far younger than him; the children so numerous they were hard to keep track of; the brutal break-ups, vicious feuds and spasms of verbal cruelty that made Freud, for many people, an impossibly sulphurous figure, a coldly brilliant predator smoking with menace. Observing him at the Jewish wedding in London of the painter RB Kitaj, the poet Stephen Spender whispered to Feaver: “I can’t stand being in the same place with Lucian. He is an evil man.” Covid-19 has created a crisis throughout the world. This crisis has produced a test of leadership. With no good options to combat a novel pathogen, countries were forced to make hard choices about how to respond. Here in the United States, our leaders have failed that test. They have taken a crisis and turned it into a tragedy. The magnitude of this failure is astonishing.

Covid-19 has created a crisis throughout the world. This crisis has produced a test of leadership. With no good options to combat a novel pathogen, countries were forced to make hard choices about how to respond. Here in the United States, our leaders have failed that test. They have taken a crisis and turned it into a tragedy. The magnitude of this failure is astonishing. In perhaps the most chaotic week of a chaotic presidency, what was most surprising about tonight’s vice-presidential debate was how oddly normal it felt.

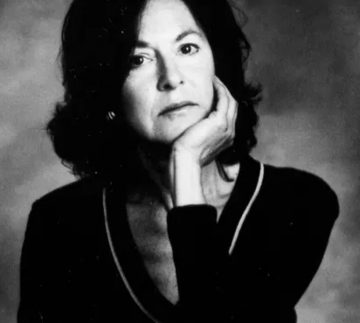

In perhaps the most chaotic week of a chaotic presidency, what was most surprising about tonight’s vice-presidential debate was how oddly normal it felt. The poet Louise Glück has become the first American woman to win the Nobel prize for literature in 27 years, cited for “her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal”.

The poet Louise Glück has become the first American woman to win the Nobel prize for literature in 27 years, cited for “her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal”.

At the first debate between Joe Biden and Donald Trump, Biden refused to say whether he’d expand the Supreme Court if Republicans confirm Barrett, insisting that the issue is a “distraction.” He’s wrong. Broaching the conversation about systemic reform after the election will be too late. And the coming Supreme Court term, which begins Monday, reflects just some of what’s at stake, this week, this month, and in the months ahead. The debate about structural changes to the court can’t wait until a hypothetical future in which everything has settled down. That future has already vanished.

At the first debate between Joe Biden and Donald Trump, Biden refused to say whether he’d expand the Supreme Court if Republicans confirm Barrett, insisting that the issue is a “distraction.” He’s wrong. Broaching the conversation about systemic reform after the election will be too late. And the coming Supreme Court term, which begins Monday, reflects just some of what’s at stake, this week, this month, and in the months ahead. The debate about structural changes to the court can’t wait until a hypothetical future in which everything has settled down. That future has already vanished.