Ian Thomson in The Guardian:

On January 1804, the West Indian island of Saint-Domingue became the world’s first black republic. The Africans toiling on the sugar-rich plantations overthrew their French masters and declared independence. The name Saint-Domingue was replaced by the aboriginal Taíno Indian word Haiti (meaning “mountainous land”) and the Haitian flag created when the white band was ceremonially ripped from the French tricolour. Two hundred years on, Haiti’s is the only successful slave revolution in history. It was led by Toussaint Louverture, a Haitian former slave and emblem of slavery’s hoped-for abolition throughout the Americas.

On January 1804, the West Indian island of Saint-Domingue became the world’s first black republic. The Africans toiling on the sugar-rich plantations overthrew their French masters and declared independence. The name Saint-Domingue was replaced by the aboriginal Taíno Indian word Haiti (meaning “mountainous land”) and the Haitian flag created when the white band was ceremonially ripped from the French tricolour. Two hundred years on, Haiti’s is the only successful slave revolution in history. It was led by Toussaint Louverture, a Haitian former slave and emblem of slavery’s hoped-for abolition throughout the Americas.

This superb new history of Louverture and his legacy portrays Saint-Domingue as the most profitable slave colony the world had ever known. The glittering prosperity of Nantes and Bordeaux, Marseilles and Dieppe, derived from commerce with the Caribbean island in coffee, indigo, cocoa and cotton; Saint- Domingue’s sugar plantations alone produced more cane than all the British West Indian islands together.

More here.

Astronomers rocked the cosmological world with the 1998 discovery that the universe is accelerating. Well-deserved Nobel Prizes were awarded to Saul Perlmutter, Brian Schmidt, and today’s guest Adam Riess. Adam has continued to push forward on investigating the structure and evolution of the universe. He’s been a leader in emphasizing a curious disagreement that threatens to grow into a crisis: incompatible values of the Hubble constant (expansion rate of the universe) obtained from the cosmic microwave background vs. direct measurements. We talk about where this “Hubble tension” comes from, and what it might mean for the universe.

Astronomers rocked the cosmological world with the 1998 discovery that the universe is accelerating. Well-deserved Nobel Prizes were awarded to Saul Perlmutter, Brian Schmidt, and today’s guest Adam Riess. Adam has continued to push forward on investigating the structure and evolution of the universe. He’s been a leader in emphasizing a curious disagreement that threatens to grow into a crisis: incompatible values of the Hubble constant (expansion rate of the universe) obtained from the cosmic microwave background vs. direct measurements. We talk about where this “Hubble tension” comes from, and what it might mean for the universe. The period since the global financial crisis has seen increased recognition, sparked in particular by the

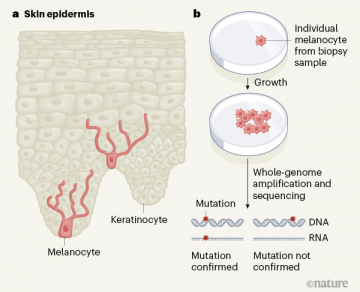

The period since the global financial crisis has seen increased recognition, sparked in particular by the  Mutations occur in our cells throughout life. Although most mutations are harmless, they accumulate in number in our tissues as we age, and if they arise in key genes, they can alter cellular behaviour and set cells on a path towards cancer. There is also speculation that somatic mutations (those in non-reproductive tissues) might contribute to ageing and to diseases unrelated to cancer. However, technical difficulties in detecting the mutations present in a small number of cells, or even in single cells, have hampered research and limited progress in understanding the first steps in cancer development and the impact of somatic mutation on ageing and disease.

Mutations occur in our cells throughout life. Although most mutations are harmless, they accumulate in number in our tissues as we age, and if they arise in key genes, they can alter cellular behaviour and set cells on a path towards cancer. There is also speculation that somatic mutations (those in non-reproductive tissues) might contribute to ageing and to diseases unrelated to cancer. However, technical difficulties in detecting the mutations present in a small number of cells, or even in single cells, have hampered research and limited progress in understanding the first steps in cancer development and the impact of somatic mutation on ageing and disease.  On September 14, 2011, we awoke once again to the image of two bodies hanging from a bridge. One man, one woman. He, tied by the hands. She, by the wrists and ankles. Just like so many other similar occurrences, and as noted in newspaper articles with a certain amount of trepidation, the bodies showed signs of having been tortured. Entrails erupted from the woman’s abdomen, opened in three different places.

On September 14, 2011, we awoke once again to the image of two bodies hanging from a bridge. One man, one woman. He, tied by the hands. She, by the wrists and ankles. Just like so many other similar occurrences, and as noted in newspaper articles with a certain amount of trepidation, the bodies showed signs of having been tortured. Entrails erupted from the woman’s abdomen, opened in three different places. The hallmarks of the Buddy Bolden myth go something like this: in the whispery pre-jazz world of turn of the twentieth century New Orleans, one titanic musical presence loomed larger than any – Bolden, the Paul Bunyan of the cornet. He played louder, harder, and hotter than any horn player before, or since. Unlike the ensembles led by his contemporaries, most or all of whom read printed sheet music on the bandstand, Bolden’s band was primarily made up of “ear” players. They were among the first (some claim the first) to bring the art of improvisation to the kinds of ensembles that preceded the advent of the musical style we now call jazz – mostly string bands and small orchestras performing marches, hymns, rags, and popular songs of the day. No recordings of Bolden and his band exist, though an unverified story persists that he made at least one Edison wax cylinder that has never been found – the Holy Grail of early jazz. But the legend that’s been handed down is that Bolden’s playing and his ability to read and draw from the energy of his adoring, excitable audiences was radical, incendiary, and transgressive.

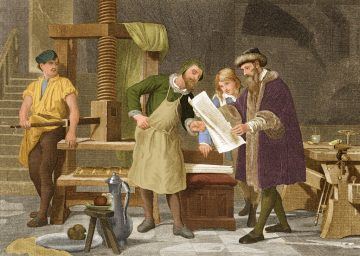

The hallmarks of the Buddy Bolden myth go something like this: in the whispery pre-jazz world of turn of the twentieth century New Orleans, one titanic musical presence loomed larger than any – Bolden, the Paul Bunyan of the cornet. He played louder, harder, and hotter than any horn player before, or since. Unlike the ensembles led by his contemporaries, most or all of whom read printed sheet music on the bandstand, Bolden’s band was primarily made up of “ear” players. They were among the first (some claim the first) to bring the art of improvisation to the kinds of ensembles that preceded the advent of the musical style we now call jazz – mostly string bands and small orchestras performing marches, hymns, rags, and popular songs of the day. No recordings of Bolden and his band exist, though an unverified story persists that he made at least one Edison wax cylinder that has never been found – the Holy Grail of early jazz. But the legend that’s been handed down is that Bolden’s playing and his ability to read and draw from the energy of his adoring, excitable audiences was radical, incendiary, and transgressive. The story of freemasonry is not all fraternal handshakes and matey slaps on the back, of course. Secrecy may be seductive, but it can also provoke wild speculation of a kind that didn’t end with the Portuguese Inquisition. Amid the violent upheavals of the French Revolution, the displaced Catholic priest Augustin Barruel could be heard denouncing revolutionary events as the consequence of a mischievous plot hatched by the brotherhood. Barruel provided little evidence for his claims, largely because there was none. But he did offer in his spectacularly successful book on the subject a template of supposed masonic machinations that has been recycled ever since. Dickie devotes some of his best chapters to this dark history of suspicion and persecution, with freemasons serving as scapegoats for Mussolini, Hitler and Franco, among many others. And today, freemasonry is banned everywhere in the Muslim world except Lebanon and Morocco.

The story of freemasonry is not all fraternal handshakes and matey slaps on the back, of course. Secrecy may be seductive, but it can also provoke wild speculation of a kind that didn’t end with the Portuguese Inquisition. Amid the violent upheavals of the French Revolution, the displaced Catholic priest Augustin Barruel could be heard denouncing revolutionary events as the consequence of a mischievous plot hatched by the brotherhood. Barruel provided little evidence for his claims, largely because there was none. But he did offer in his spectacularly successful book on the subject a template of supposed masonic machinations that has been recycled ever since. Dickie devotes some of his best chapters to this dark history of suspicion and persecution, with freemasons serving as scapegoats for Mussolini, Hitler and Franco, among many others. And today, freemasonry is banned everywhere in the Muslim world except Lebanon and Morocco. The “democracy” under attack today is a shorthand for liberal democracy, and what is really under greatest threat is the liberal component of this pair. The democracy part refers to the accountability of those who hold political power through mechanisms like free and fair multiparty elections under universal adult franchise. The liberal part, by contrast, refers primarily to a rule of law that constrains the power of government and requires that even the most powerful actors in the system operate under the same general rules as ordinary citizens. Liberal democracies, in other words, have a constitutional system of checks and balances that limits the power of elected leaders.

The “democracy” under attack today is a shorthand for liberal democracy, and what is really under greatest threat is the liberal component of this pair. The democracy part refers to the accountability of those who hold political power through mechanisms like free and fair multiparty elections under universal adult franchise. The liberal part, by contrast, refers primarily to a rule of law that constrains the power of government and requires that even the most powerful actors in the system operate under the same general rules as ordinary citizens. Liberal democracies, in other words, have a constitutional system of checks and balances that limits the power of elected leaders. The

The

Penrose hails from one of the great intellectual dynasties of the 20th century. His father Lionel was a distinguished psychiatrist and geneticist, his uncle was the surrealist artist Roland Penrose. Roger was one of four children; older brother Oliver became a theoretical physicist, younger brother Jonathan was British chess champion a record-breaking 10 times, and sister Shirley Hodgson is a professor of cancer genetics.

Penrose hails from one of the great intellectual dynasties of the 20th century. His father Lionel was a distinguished psychiatrist and geneticist, his uncle was the surrealist artist Roland Penrose. Roger was one of four children; older brother Oliver became a theoretical physicist, younger brother Jonathan was British chess champion a record-breaking 10 times, and sister Shirley Hodgson is a professor of cancer genetics. According to copies of copies of fragments of ancient texts, Pythagoras in about 500 B.C. exhorted his followers: Don’t eat beans! Why he issued this prohibition is anybody’s guess (Aristotle thought he knew), but it doesn’t much matter because the idea never caught on. According to Joseph Henrich, some unknown early church fathers about a thousand years later promulgated the edict: Don’t marry your cousin! Why they did this is also unclear, but if Henrich is right — and he develops a fascinating case brimming with evidence — this prohibition changed the face of the world, by eventually creating societies and people that were WEIRD: Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic. In the argument put forward in this engagingly written, excellently organized and meticulously argued book, this simple rule triggered a cascade of changes, creating states to replace tribes, science to replace lore and law to replace custom. If you are reading this you are very probably WEIRD, and so are almost all of your friends and associates, but we are outliers on many psychological measures.

According to copies of copies of fragments of ancient texts, Pythagoras in about 500 B.C. exhorted his followers: Don’t eat beans! Why he issued this prohibition is anybody’s guess (Aristotle thought he knew), but it doesn’t much matter because the idea never caught on. According to Joseph Henrich, some unknown early church fathers about a thousand years later promulgated the edict: Don’t marry your cousin! Why they did this is also unclear, but if Henrich is right — and he develops a fascinating case brimming with evidence — this prohibition changed the face of the world, by eventually creating societies and people that were WEIRD: Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic. In the argument put forward in this engagingly written, excellently organized and meticulously argued book, this simple rule triggered a cascade of changes, creating states to replace tribes, science to replace lore and law to replace custom. If you are reading this you are very probably WEIRD, and so are almost all of your friends and associates, but we are outliers on many psychological measures.