Jeremiah Moss at n+1:

ON MY DOORMAT, a large, greasy-golden rat is curled as if sleeping, tucked into the corner where my apartment door meets the wall of the hallway. Her dark, shining eyes are open. I can’t tell if she’s dead or dying, alive enough to dart into my apartment, so I close the door quick. I can’t get out of my apartment without stepping over the rat and I have no intention of doing that. She gives me the shivers. In twenty-five years, I have never seen a rat inside the building and this weird intrusion concerns me as an indication of entropic breakdown in the system gone too far. When the exterminator comes for his monthly visit, he will tell me that, since the pandemic began, the rats of New York have been leaving the subterranean zone to venture upwards into buildings, into hallways and apartments, searching for food. This, he will say, is unusual behavior for a rat.

ON MY DOORMAT, a large, greasy-golden rat is curled as if sleeping, tucked into the corner where my apartment door meets the wall of the hallway. Her dark, shining eyes are open. I can’t tell if she’s dead or dying, alive enough to dart into my apartment, so I close the door quick. I can’t get out of my apartment without stepping over the rat and I have no intention of doing that. She gives me the shivers. In twenty-five years, I have never seen a rat inside the building and this weird intrusion concerns me as an indication of entropic breakdown in the system gone too far. When the exterminator comes for his monthly visit, he will tell me that, since the pandemic began, the rats of New York have been leaving the subterranean zone to venture upwards into buildings, into hallways and apartments, searching for food. This, he will say, is unusual behavior for a rat.

more here.

When I was a teenager I was, like most teenagers, preoccupied with the idea that somewhere on the horizon there was a Now. The present moment came to a peak out there; it achieved a continuous apotheosis of nowness, a wave endlessly breaking on an invisible shore. I wasn’t quite sure what specific form this climax took, but it had to involve some concatenation of records, poems, pictures, parties, and behavior. Out there all of those items would be somehow made manifest: the pictures walking along in the middle of the street, the right song broadcast in the air every minute, the parties behaving like the poems and vice versa. Since it was 1967 when I became a teenager, I suspected that the Now would stir together rock ’n’ roll bands and mod girls and cigarettes and bearded poets and sunglasses and Italian movie stars and pointy shoes and spies. But there had to be much more than that, things I could barely guess. The present would be occurring in New York and Paris and London and California while I lay in my narrow bed in New Jersey, which was a swamplike clot of the dead recent past.

When I was a teenager I was, like most teenagers, preoccupied with the idea that somewhere on the horizon there was a Now. The present moment came to a peak out there; it achieved a continuous apotheosis of nowness, a wave endlessly breaking on an invisible shore. I wasn’t quite sure what specific form this climax took, but it had to involve some concatenation of records, poems, pictures, parties, and behavior. Out there all of those items would be somehow made manifest: the pictures walking along in the middle of the street, the right song broadcast in the air every minute, the parties behaving like the poems and vice versa. Since it was 1967 when I became a teenager, I suspected that the Now would stir together rock ’n’ roll bands and mod girls and cigarettes and bearded poets and sunglasses and Italian movie stars and pointy shoes and spies. But there had to be much more than that, things I could barely guess. The present would be occurring in New York and Paris and London and California while I lay in my narrow bed in New Jersey, which was a swamplike clot of the dead recent past. The smart play for Trump is to postpone the nomination to reduce the risk of Democratic mobilization, and to warn Republicans of the risks should he lose. Trump’s people do not usually execute the smart play. They are often the victims of the hyper-ideological media they consume, which deceive them about what actually is the smart play. This time, though, they may just be desperate enough to break long-standing pattern and try something different.

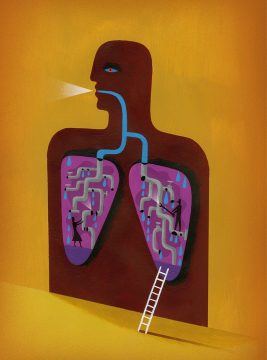

The smart play for Trump is to postpone the nomination to reduce the risk of Democratic mobilization, and to warn Republicans of the risks should he lose. Trump’s people do not usually execute the smart play. They are often the victims of the hyper-ideological media they consume, which deceive them about what actually is the smart play. This time, though, they may just be desperate enough to break long-standing pattern and try something different. Over the course of two decades spent developing treatments for the genetic lung disease cystic fibrosis, biologist Fredrick Van Goor has had hundreds of conversations with patients. But he remembers one in particular. The discussion was about the genetics of cystic fibrosis, a disease that develops when a person inherits two faulty copies of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. This gene encodes the CFTR protein, which resides in the cell membrane and transports chloride and bicarbonate ions out of the cell. More than 2,000 variants of CFTR have been identified, and more than 350 of them are known to produce enough disruption in the protein’s function to trigger the debilitating and life-shortening condition. The focus of the conversation was the inevitable inequities of personalized medicine, which can be highly effective for people who meet certain criteria, but will leave others behind — as was the case for this patient. “He described it as being on a sinking ship, when all of the other lifeboats have left,” Van Goor recalls. “That image has stuck with me.”

Over the course of two decades spent developing treatments for the genetic lung disease cystic fibrosis, biologist Fredrick Van Goor has had hundreds of conversations with patients. But he remembers one in particular. The discussion was about the genetics of cystic fibrosis, a disease that develops when a person inherits two faulty copies of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. This gene encodes the CFTR protein, which resides in the cell membrane and transports chloride and bicarbonate ions out of the cell. More than 2,000 variants of CFTR have been identified, and more than 350 of them are known to produce enough disruption in the protein’s function to trigger the debilitating and life-shortening condition. The focus of the conversation was the inevitable inequities of personalized medicine, which can be highly effective for people who meet certain criteria, but will leave others behind — as was the case for this patient. “He described it as being on a sinking ship, when all of the other lifeboats have left,” Van Goor recalls. “That image has stuck with me.” “Prisons are created internally / and are found everywhere.” My conversations with Spoon Jackson keep returning to this point, a line from one of his poems. Prisons are both real and imaginary. All people experience some kind of prison, some to a greater degree than others. Those degrees are not coincidental. Jackson, a 63-year-old Black man, has been serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole for 42 years and has lived in a series of prisons. He discovered poetry one day, about 30 years ago, sitting in his cell, looking over the bay at San Quentin. At least that’s how he tells it.

“Prisons are created internally / and are found everywhere.” My conversations with Spoon Jackson keep returning to this point, a line from one of his poems. Prisons are both real and imaginary. All people experience some kind of prison, some to a greater degree than others. Those degrees are not coincidental. Jackson, a 63-year-old Black man, has been serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole for 42 years and has lived in a series of prisons. He discovered poetry one day, about 30 years ago, sitting in his cell, looking over the bay at San Quentin. At least that’s how he tells it. There are as many as 9 million feral swine across the U.S., their populations having expanded from about 17 states to 38 over the last three decades. Canada doesn’t have comparable data, but Ryan Brook, a University of Saskatchewan biologist who researches wild pigs, predicts that they will occupy 386,000 square miles across the country by the end of 2020, and they’re currently expanding at about 35,000 square miles a year.

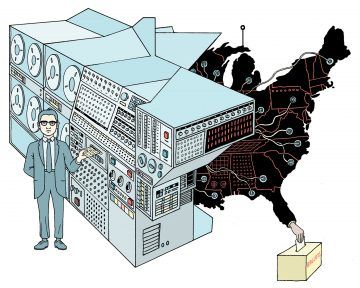

There are as many as 9 million feral swine across the U.S., their populations having expanded from about 17 states to 38 over the last three decades. Canada doesn’t have comparable data, but Ryan Brook, a University of Saskatchewan biologist who researches wild pigs, predicts that they will occupy 386,000 square miles across the country by the end of 2020, and they’re currently expanding at about 35,000 square miles a year.

For good reason, The Great Gatsby is one of the most admired and talked-about books of the twentieth century. And that reason is, of course, that it’s really short—47,094 words, to be exact. I read it for the first time in a few hours at a swim meet (the aptness of the setting wasn’t clear to me until Chapter 8) and probably would have finished sooner had it not been for the snatches of Eminem coming from somebody’s boombox. You can count the book’s speaking roles on your fingers, and any high school sophomore can skim it the night before the big exam. Assign that to millions of teenagers for sixty-odd years, and a Great American Novel is born.

For good reason, The Great Gatsby is one of the most admired and talked-about books of the twentieth century. And that reason is, of course, that it’s really short—47,094 words, to be exact. I read it for the first time in a few hours at a swim meet (the aptness of the setting wasn’t clear to me until Chapter 8) and probably would have finished sooner had it not been for the snatches of Eminem coming from somebody’s boombox. You can count the book’s speaking roles on your fingers, and any high school sophomore can skim it the night before the big exam. Assign that to millions of teenagers for sixty-odd years, and a Great American Novel is born. What is it about the proposal that strikes me as so disturbing?’ Reading through an article describing a local government measure, I feel opposition rising within me. Normally, forming an opinion about such things would take me some time. But not here. The proposal instantly strikes me as unjust. My reaction is not just intellectual; it is visceral. My emotions are engaged. My imagination is exercised. As I imagine the proposal playing out in practice, the distinctive brand of injustice seems to be jumping out of every word on the page.

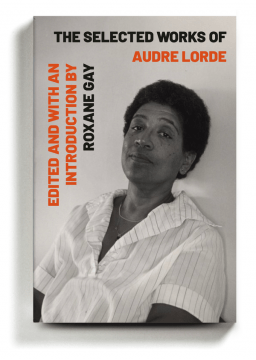

What is it about the proposal that strikes me as so disturbing?’ Reading through an article describing a local government measure, I feel opposition rising within me. Normally, forming an opinion about such things would take me some time. But not here. The proposal instantly strikes me as unjust. My reaction is not just intellectual; it is visceral. My emotions are engaged. My imagination is exercised. As I imagine the proposal playing out in practice, the distinctive brand of injustice seems to be jumping out of every word on the page. Lorde loved to be in dialogue, loved thinking with others, with her comrades and lovers. She is never alone on the page. Even her short essays come festooned with long lines of acknowledgment to those who have sharpened their ideas. Ghosts flock her essays. She writes to the ancestors and to women she meets in the headlines of the newspaper — missing women, murdered women, naming as many as she can, the sort of rescue and care for the dead that one sees in the work of Saidiya Hartman and Christina Sharpe. In “The Cancer Journals,” in which she documented her diagnosis of breast cancer, she noted: “I carry tattooed upon my heart a list of names of women who did not survive, and there is always a space left for one more, my own.”

Lorde loved to be in dialogue, loved thinking with others, with her comrades and lovers. She is never alone on the page. Even her short essays come festooned with long lines of acknowledgment to those who have sharpened their ideas. Ghosts flock her essays. She writes to the ancestors and to women she meets in the headlines of the newspaper — missing women, murdered women, naming as many as she can, the sort of rescue and care for the dead that one sees in the work of Saidiya Hartman and Christina Sharpe. In “The Cancer Journals,” in which she documented her diagnosis of breast cancer, she noted: “I carry tattooed upon my heart a list of names of women who did not survive, and there is always a space left for one more, my own.” Adam Tooze in The Guardian:

Adam Tooze in The Guardian: Lynn Parramore interviews Lance Taylor over at INET:

Lynn Parramore interviews Lance Taylor over at INET: Michael Scott Moore in the LA Review of Books:

Michael Scott Moore in the LA Review of Books: