Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin talk to C. J. Polychroniou in Boston Review:

Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin talk to C. J. Polychroniou in Boston Review:

C. J. Polychroniou: How does the coronavirus pandemic, and the response to it, shed light on how we should think about climate change and the prospects for a global Green New Deal?

Noam Chomsky: At the time of writing, concern for the COVID-19 crisis is virtually all-consuming. That’s understandable. It is severe and is severely disrupting lives. But it will pass, though at horrendous cost, and there will be recovery. There will not be recovery from the melting of the arctic ice sheets and the other consequences of global warming.

Not everyone is ignoring the advancing existential crisis. The sociopaths dedicated to accelerating the disaster continue to pursue their efforts, relentlessly. As before, Trump and his courtiers take pride in leading the race to destruction. As the United States was becoming the epicenter of the pandemic, thanks in no small measure to their folly, the White House cabal released its budget proposals. As expected, the proposals call for even deeper cuts in healthcare support and environmental protection, instead favoring the bloated military and the building of Trump’s Great Wall. And to add an extra touch of sadism, “the budget promotes a fossil fuel ‘energy boom’ in the United States, including an increase in the production of natural gas and crude oil.”

More here.

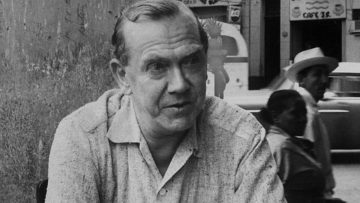

Joseph Conrad’s death made Graham Greene feel, at 19, sitting on a beach in Yorkshire, ‘as if there was a kind of “blank” in the whole of contemporary literature’. Greene’s own death in 1991, aged 87, had a similar effect on many younger writers, myself included. For John le Carré, his most obvious successor, Greene had ‘carried the torch of English literature, almost alone’. His cool fugitive presence, in Martin Amis’s phrase, had been there all our reading lives. In an age of diminishing faith, he had used Catholic parables in a way that lent them a power beyond their biblical origins, mining the gospels rather as le Carré has mined the Cold War. Shaking his hand in Moscow in 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev spoke for an international audience: ‘I have known you for some years, Mr Greene’ — although it was unclear whether as an admirer of his novels, or if Russia’s president had seen his name in intelligence reports concerning Latin America.

Joseph Conrad’s death made Graham Greene feel, at 19, sitting on a beach in Yorkshire, ‘as if there was a kind of “blank” in the whole of contemporary literature’. Greene’s own death in 1991, aged 87, had a similar effect on many younger writers, myself included. For John le Carré, his most obvious successor, Greene had ‘carried the torch of English literature, almost alone’. His cool fugitive presence, in Martin Amis’s phrase, had been there all our reading lives. In an age of diminishing faith, he had used Catholic parables in a way that lent them a power beyond their biblical origins, mining the gospels rather as le Carré has mined the Cold War. Shaking his hand in Moscow in 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev spoke for an international audience: ‘I have known you for some years, Mr Greene’ — although it was unclear whether as an admirer of his novels, or if Russia’s president had seen his name in intelligence reports concerning Latin America. In 2014, Kate Livingston

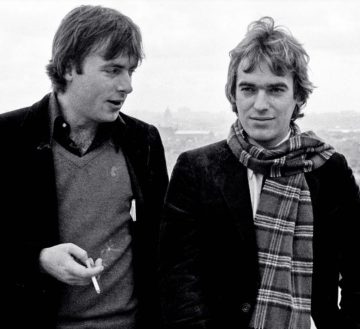

In 2014, Kate Livingston  It would hardly have surprised Christopher Hitchens, his unsanguine views of the afterlife under no bushel, that among the trials and stations awaiting his departed soul there would be passage through a Martin Amis novel (he had already endured being packed into The Pregnant Widow in the character of Nicholas Shackleton). Inside Story – the Fleet Street tease of the title notwithstanding – evinces a protective, even proprietary attitude towards the goods to be delivered. The cover features an arresting image of the two grands amis – both formerly of this parish – on the cusp of their prime. Hitchens is on the left, holding his cigarette mid-abdomen like a paintbrush. His as yet unravaged face seems to be gauging whether his last remark has landed with Amis, who looks into the distance, appearing simultaneously satisfied and anxious.

It would hardly have surprised Christopher Hitchens, his unsanguine views of the afterlife under no bushel, that among the trials and stations awaiting his departed soul there would be passage through a Martin Amis novel (he had already endured being packed into The Pregnant Widow in the character of Nicholas Shackleton). Inside Story – the Fleet Street tease of the title notwithstanding – evinces a protective, even proprietary attitude towards the goods to be delivered. The cover features an arresting image of the two grands amis – both formerly of this parish – on the cusp of their prime. Hitchens is on the left, holding his cigarette mid-abdomen like a paintbrush. His as yet unravaged face seems to be gauging whether his last remark has landed with Amis, who looks into the distance, appearing simultaneously satisfied and anxious. In the 1940s, trailblazing physicists stumbled upon the next layer of reality. Particles were out, and fields — expansive, undulating entities that fill space like an ocean — were in. One ripple in a field would be an electron, another a photon, and interactions between them seemed to explain all electromagnetic events.

In the 1940s, trailblazing physicists stumbled upon the next layer of reality. Particles were out, and fields — expansive, undulating entities that fill space like an ocean — were in. One ripple in a field would be an electron, another a photon, and interactions between them seemed to explain all electromagnetic events. Every year, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation releases a Goalkeepers report, tracking the world’s progress toward the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals. The news is almost always pretty good. This year’s edition is … not like that. “Almost every time we have opened our mouths or put pen to paper,” the Gateses write in the report’s introduction, “we have celebrated decades of historic progress in fighting poverty and disease. But we have to confront the current reality with candor: This progress has now stopped.” Their annual report tracks global progress on 18 different metrics. “In recent years, the world has improved on every single one. This year, on the vast majority, we’ve regressed.”

Every year, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation releases a Goalkeepers report, tracking the world’s progress toward the U.N.’s Sustainable Development Goals. The news is almost always pretty good. This year’s edition is … not like that. “Almost every time we have opened our mouths or put pen to paper,” the Gateses write in the report’s introduction, “we have celebrated decades of historic progress in fighting poverty and disease. But we have to confront the current reality with candor: This progress has now stopped.” Their annual report tracks global progress on 18 different metrics. “In recent years, the world has improved on every single one. This year, on the vast majority, we’ve regressed.” America is a country in deep pain. The coronavirus pandemic, racial injustice, economic insecurity, political polarization, misinformation and general daily uncertainty dominate our lives to the point that many people are barely able to cope. And life wasn’t exactly a cakewalk before 2020. Out of all the fears, stresses and indignities our citizens are living with, there emerges a kind of primal insecurity that undermines every aspect of life right now. It’s no wonder that anxiety, depression and other psychological problems are on the rise.

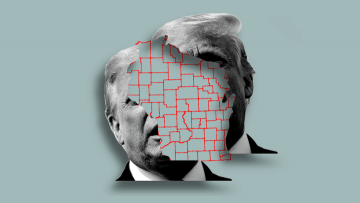

America is a country in deep pain. The coronavirus pandemic, racial injustice, economic insecurity, political polarization, misinformation and general daily uncertainty dominate our lives to the point that many people are barely able to cope. And life wasn’t exactly a cakewalk before 2020. Out of all the fears, stresses and indignities our citizens are living with, there emerges a kind of primal insecurity that undermines every aspect of life right now. It’s no wonder that anxiety, depression and other psychological problems are on the rise. No state has haunted the Democratic Party’s imagination for the past four years like Wisconsin. While it was not the only state that killed Hillary Clinton’s presidential hopes in 2016, it was the one where the knife plunged deepest. Clinton was so confident about Wisconsin that she never even campaigned there. This year, it is one of the most fiercely contested states. The Democrats planned to hold their convention in Milwaukee, before the coronavirus pandemic forced its cancellation. Donald Trump is also making a strong play for Wisconsin. Trump’s weaknesses with the electorate are familiar: Voters find him coarse, and they deplore his handling of race, the coronavirus, and protests. One recent YouGov poll

No state has haunted the Democratic Party’s imagination for the past four years like Wisconsin. While it was not the only state that killed Hillary Clinton’s presidential hopes in 2016, it was the one where the knife plunged deepest. Clinton was so confident about Wisconsin that she never even campaigned there. This year, it is one of the most fiercely contested states. The Democrats planned to hold their convention in Milwaukee, before the coronavirus pandemic forced its cancellation. Donald Trump is also making a strong play for Wisconsin. Trump’s weaknesses with the electorate are familiar: Voters find him coarse, and they deplore his handling of race, the coronavirus, and protests. One recent YouGov poll  Is language adequate to describe experience? Are words good enough?

Is language adequate to describe experience? Are words good enough? For me the deeper interest of Struth’s photograph is thematic: the upper half of the composition is dominated by the under-surface of the Space Shuttle with its diagonal grid of heat-defying ceramic tiles; the implication is that the young woman in the left foreground and perhaps also the two men farther back and to the right are working on these. That they are doing so is nothing less than a matter of life and death. That is, it is absolutely crucial to the success of the Shuttle’s missions and the survival of the astronauts inside it that the tiles resist the formidable heat of reentry and even more that they do not come loose from the surface of the Shuttle. This may seem to go without saying, and in a sense it does, but taking this photograph as thematic for the series as a whole (as its position early in the exhibition catalogue encourages one to do), it also suggests that there will be no tendency in the series to shift the implied locus of agency away from human beings to the technology itself—a point driven home by the fact that this is the only one of the technology photographs to include human agents.

For me the deeper interest of Struth’s photograph is thematic: the upper half of the composition is dominated by the under-surface of the Space Shuttle with its diagonal grid of heat-defying ceramic tiles; the implication is that the young woman in the left foreground and perhaps also the two men farther back and to the right are working on these. That they are doing so is nothing less than a matter of life and death. That is, it is absolutely crucial to the success of the Shuttle’s missions and the survival of the astronauts inside it that the tiles resist the formidable heat of reentry and even more that they do not come loose from the surface of the Shuttle. This may seem to go without saying, and in a sense it does, but taking this photograph as thematic for the series as a whole (as its position early in the exhibition catalogue encourages one to do), it also suggests that there will be no tendency in the series to shift the implied locus of agency away from human beings to the technology itself—a point driven home by the fact that this is the only one of the technology photographs to include human agents. Like many of the virus’s hardest hit victims, the United States went into the

Like many of the virus’s hardest hit victims, the United States went into the  Researchers at the

Researchers at the  In an age of visual profusion, when the vividness and abundance of images consumed for distraction and commerce is breathtaking, it might seem naive for an artist to try to create images of incantatory, even magical power. To seek a holy relationship to the image today is often seen as foolhardy.

In an age of visual profusion, when the vividness and abundance of images consumed for distraction and commerce is breathtaking, it might seem naive for an artist to try to create images of incantatory, even magical power. To seek a holy relationship to the image today is often seen as foolhardy. For many of the artists in this book, music and performance’s inherent haziness is able to envelop everything in an intoxicating fog, which allows artists the freedom to try on different gender identities without always revealing where, exactly, their “authentic” selves begin. (Of course, it offers similar possibilities to the complex and questioning people listening, too.) This is the “alternate ribbon of time”—a phrase Geffen borrows from the queer indie pop star Perfume Genius—that links the butch blues singer Lucille Bogan’s 1935 recording of “BD Woman’s Blues” (the initials stood for “bull dyke”) with, say, the crusading punk group Against Me!’s 2007 song “The Ocean.” Five years before the band’s front person Laura Jane Grace came out as a transgender woman, she sang in that song, “If I could have chosen, I would have been born a woman / My mother once told me she would have named me Laura.” Presuming poetic license, no one batted an eyelash. Grace “assumed everyone around her would pick up on her overt confession of dysphoria,” Geffen writes, “but couched in a song, it glanced off the world.”

For many of the artists in this book, music and performance’s inherent haziness is able to envelop everything in an intoxicating fog, which allows artists the freedom to try on different gender identities without always revealing where, exactly, their “authentic” selves begin. (Of course, it offers similar possibilities to the complex and questioning people listening, too.) This is the “alternate ribbon of time”—a phrase Geffen borrows from the queer indie pop star Perfume Genius—that links the butch blues singer Lucille Bogan’s 1935 recording of “BD Woman’s Blues” (the initials stood for “bull dyke”) with, say, the crusading punk group Against Me!’s 2007 song “The Ocean.” Five years before the band’s front person Laura Jane Grace came out as a transgender woman, she sang in that song, “If I could have chosen, I would have been born a woman / My mother once told me she would have named me Laura.” Presuming poetic license, no one batted an eyelash. Grace “assumed everyone around her would pick up on her overt confession of dysphoria,” Geffen writes, “but couched in a song, it glanced off the world.”