After the Election: A Father Speaks to His Son

He says, they will not take us.

They want the ones who love

another god, the ones whose

joy comes with five prayers and

songs to the sun in the mornings

and at night. He says, they will

not want us. They want the ones

whose tongues stumble over

silent e’s, whose voices creak

when a th suddenly appears

in the middle of a word.

They want the ones who cannot hide

copper skin like we can. He says,

I am old. I lived through one revolution.

We can hide our skin.

We have read the books.

He says, we are the quiet kind, the ones

who stay late and do not speak,

the ones who do not bring trumpets

or trouble. He says, we are safe in silence.

We must become ghosts.

I think, so many are already dust.

tried to stay thin, be small, tried

breaking bone and voice, tried

to be soft. So many tried to be

empty, to be barely breath. To be

still enough to be left alone. Become

shadows, trying not to be bodies.

It never works. To become nothing.

They come for the shadows, too.

by M. Soledad Caballero

from Split This Rock

When he died in 1677 at the age of forty-four, Spinoza left behind a compact Latin manuscript, Ethics, and his disciples quickly got it printed. It is a book like no other. It urges us to change our whole way of thinking and in particular to rid ourselves of the deep-rooted conceit that makes us imagine that our petty, transient lives might have some ultimate significance. The argument is dynamic, disruptive and upsetting, but it is contained within a literary framework of extraordinary austerity, comprising an array of definitions, axioms, propositions, proofs and scholia. The overall effect is not so much beautiful as sublime, like watching a massive fortress being shaken by storms and earthquakes. Many readers have found themselves deeply moved by Ethics but unable to say exactly what it means.

When he died in 1677 at the age of forty-four, Spinoza left behind a compact Latin manuscript, Ethics, and his disciples quickly got it printed. It is a book like no other. It urges us to change our whole way of thinking and in particular to rid ourselves of the deep-rooted conceit that makes us imagine that our petty, transient lives might have some ultimate significance. The argument is dynamic, disruptive and upsetting, but it is contained within a literary framework of extraordinary austerity, comprising an array of definitions, axioms, propositions, proofs and scholia. The overall effect is not so much beautiful as sublime, like watching a massive fortress being shaken by storms and earthquakes. Many readers have found themselves deeply moved by Ethics but unable to say exactly what it means.

Remarkably, in these fractious times, President Trump has managed to forge a singular area of consensus among liberals and conservatives, Republicans and Democrats: Nearly everyone seems to agree that he represents a throwback to a vintage version of manhood. After Mr. Trump proclaimed his “domination” over coronavirus, saluting Marine One and ripping off his mask, the Fox News host Greg Gutfeld cast the president in cinematic World War II terms — a tough-as-nails platoon leader who “put himself on the line” rather than abandon the troops. “He didn’t hide from the virus,”

Remarkably, in these fractious times, President Trump has managed to forge a singular area of consensus among liberals and conservatives, Republicans and Democrats: Nearly everyone seems to agree that he represents a throwback to a vintage version of manhood. After Mr. Trump proclaimed his “domination” over coronavirus, saluting Marine One and ripping off his mask, the Fox News host Greg Gutfeld cast the president in cinematic World War II terms — a tough-as-nails platoon leader who “put himself on the line” rather than abandon the troops. “He didn’t hide from the virus,”  American society is prone, political theorist Langdon Winner wrote in 2005, to “technological euphoria,” each bout of which is inevitably followed by a period of letdown and reassessment. Perhaps in part for this reason, reviewing the history of digital democracy feels like watching the same movie over and over again. Even Winner’s point has that quality: He first made it in the mid-eighties and has repeated it in every decade since. In the same vein, Warren Yoder, longtime director of the Public Policy Center of Mississippi, responded to the Pew survey by arguing that we have reached the inevitable “low point” with digital technology—as “has happened many times in the past with pamphleteers, muckraking newspapers, radio, deregulated television.” (“Things will get better,” Yoder cheekily adds, “just in time for a new generational crisis beginning soon after 2030.”)

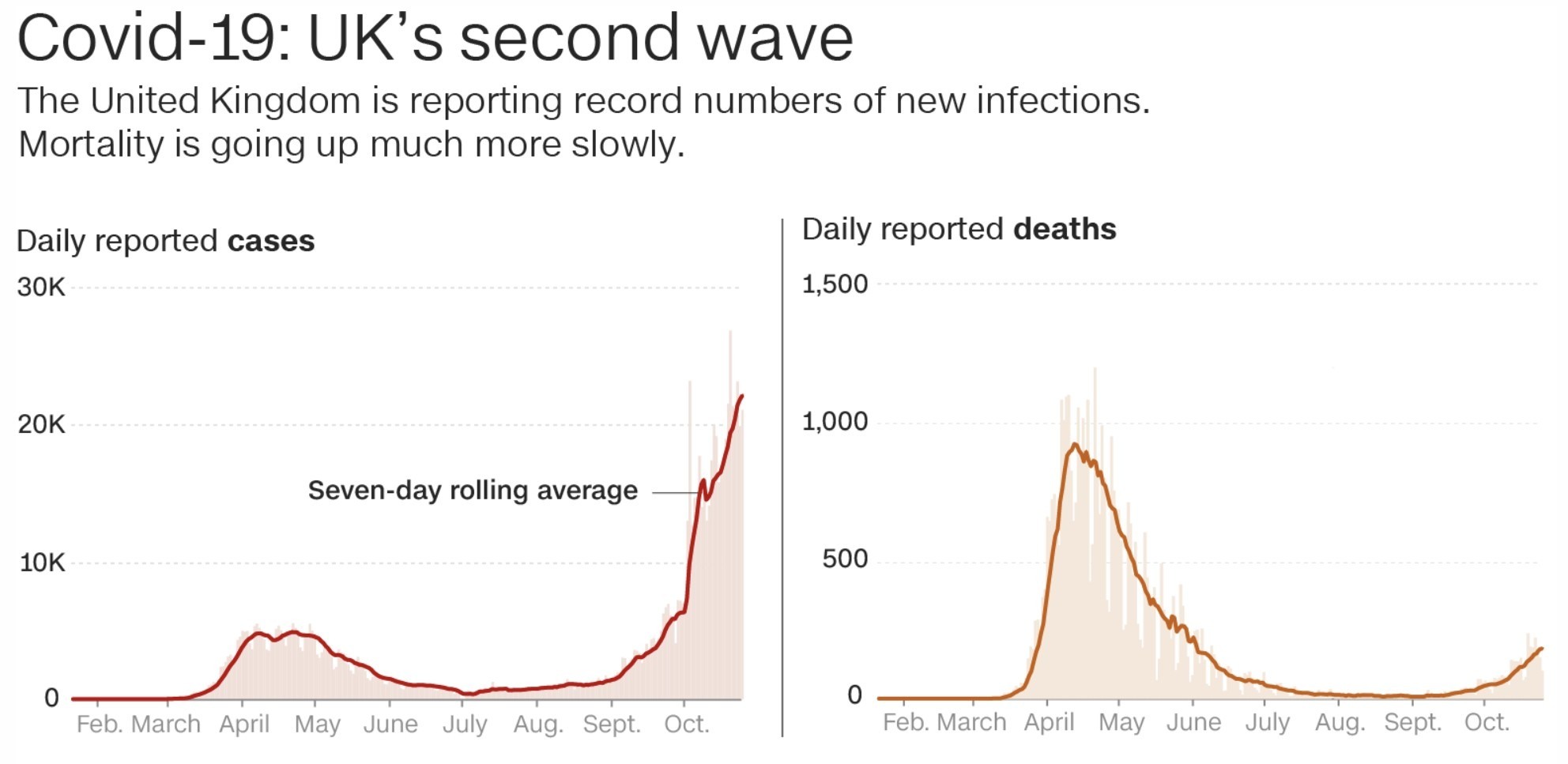

American society is prone, political theorist Langdon Winner wrote in 2005, to “technological euphoria,” each bout of which is inevitably followed by a period of letdown and reassessment. Perhaps in part for this reason, reviewing the history of digital democracy feels like watching the same movie over and over again. Even Winner’s point has that quality: He first made it in the mid-eighties and has repeated it in every decade since. In the same vein, Warren Yoder, longtime director of the Public Policy Center of Mississippi, responded to the Pew survey by arguing that we have reached the inevitable “low point” with digital technology—as “has happened many times in the past with pamphleteers, muckraking newspapers, radio, deregulated television.” (“Things will get better,” Yoder cheekily adds, “just in time for a new generational crisis beginning soon after 2030.”) Recent case and fatality figures from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) show that while recorded Covid-19 cases are spiking in the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Germany and other European countries, deaths are not rising at the same rate.

Recent case and fatality figures from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) show that while recorded Covid-19 cases are spiking in the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Germany and other European countries, deaths are not rising at the same rate.

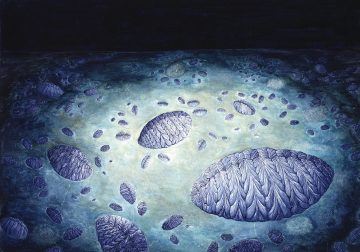

The revolutionary animal lived and died in the muck. In its final hours, it inched across the sea floor, leaving a track like a tyre print, and finally went still. Then geology set to work. Over the next half a billion years, sediment turned to stone, preserving the deathbed scene. The fossilized creature looks like a piece of frayed rope measuring just a few centimetres wide. But it was a trailblazer among living things. This was the earliest-known animal to show unequivocal evidence of two momentous innovations packaged together: the ability to roam the ocean floor, and a body built from segments. It was also among the oldest known to have clear front and back ends, and a left side that mirrored its right. Those same features are found today in animals from flies to flying foxes, from lobsters to lions.

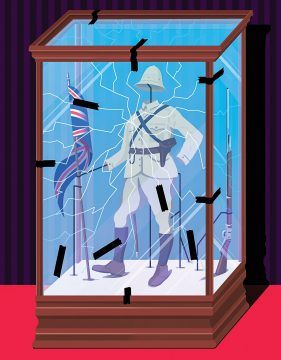

The revolutionary animal lived and died in the muck. In its final hours, it inched across the sea floor, leaving a track like a tyre print, and finally went still. Then geology set to work. Over the next half a billion years, sediment turned to stone, preserving the deathbed scene. The fossilized creature looks like a piece of frayed rope measuring just a few centimetres wide. But it was a trailblazer among living things. This was the earliest-known animal to show unequivocal evidence of two momentous innovations packaged together: the ability to roam the ocean floor, and a body built from segments. It was also among the oldest known to have clear front and back ends, and a left side that mirrored its right. Those same features are found today in animals from flies to flying foxes, from lobsters to lions. On a cloud-spackled Sunday last June, protesters in Bristol, England, gathered at a statue of Edward Colston, a seventeenth-century slave trader on whose watch more than eighty thousand Africans were trafficked across the Atlantic. “Pull it down!” the crowd chanted, as people yanked on a rope around the statue’s neck. A few tugs, and the figure clanged off its pedestal. A panel of its coat skirt cracked off to expose a hollow buttock as the demonstrators rolled the statue toward the harbor, a few hundred yards away, and then tipped it headlong into the water.

On a cloud-spackled Sunday last June, protesters in Bristol, England, gathered at a statue of Edward Colston, a seventeenth-century slave trader on whose watch more than eighty thousand Africans were trafficked across the Atlantic. “Pull it down!” the crowd chanted, as people yanked on a rope around the statue’s neck. A few tugs, and the figure clanged off its pedestal. A panel of its coat skirt cracked off to expose a hollow buttock as the demonstrators rolled the statue toward the harbor, a few hundred yards away, and then tipped it headlong into the water. And yet, despite his shifting placement in the dynamic force field of cultural politics, Steiner resisted turning into a curmudgeonly apologist for a world on the wane or allowing his Kulturpessimismus to sanction a resentful withdrawal from the public arena. In fact, one of the hallmarks of his career was a willingness to remain suspended within paradoxes, never forcing a simple choice between unpalatable options. This attitude was already evident in Language and Silence, which both celebrates humanistic high culture and acknowledges that the Holocaust has disabused us of the naïve illusion that it humanizes those who uphold it. Or as he put it in what is perhaps his most frequently cited sentences: “We come after. We know now that a man can read Goethe or Rilke in the evening, that he can play Bach or Schubert, and go to his day’s work at Auschwitz in the morning.”

And yet, despite his shifting placement in the dynamic force field of cultural politics, Steiner resisted turning into a curmudgeonly apologist for a world on the wane or allowing his Kulturpessimismus to sanction a resentful withdrawal from the public arena. In fact, one of the hallmarks of his career was a willingness to remain suspended within paradoxes, never forcing a simple choice between unpalatable options. This attitude was already evident in Language and Silence, which both celebrates humanistic high culture and acknowledges that the Holocaust has disabused us of the naïve illusion that it humanizes those who uphold it. Or as he put it in what is perhaps his most frequently cited sentences: “We come after. We know now that a man can read Goethe or Rilke in the evening, that he can play Bach or Schubert, and go to his day’s work at Auschwitz in the morning.”

Agatha Christie was in her mid-20s when, in 1916, she took up what seemed the improbable endeavor of penning her first detective novel. It was so unlikely, in fact, that her elder sister, Madge, with whom she had always competed, dared Agatha to accomplish the feat, certain of her sibling’s eventual failure.

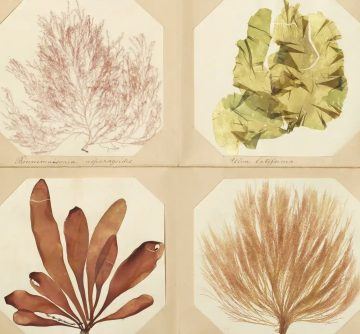

Agatha Christie was in her mid-20s when, in 1916, she took up what seemed the improbable endeavor of penning her first detective novel. It was so unlikely, in fact, that her elder sister, Madge, with whom she had always competed, dared Agatha to accomplish the feat, certain of her sibling’s eventual failure. On his first day as the new science director for the Monterey Bay Aquarium in

On his first day as the new science director for the Monterey Bay Aquarium in  Senator John Cornyn of Texas, locked in his own tight re-election race, recently told the local media that he, too, has disagreed with Mr. Trump on numerous issues, including deficit spending, trade policy and his raiding of the defense budget. Mr. Cornyn said he opted to keep his opposition private rather than get into a public tiff with Mr. Trump “because, as I’ve observed, those usually don’t end too well.”

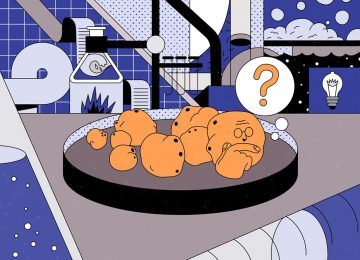

Senator John Cornyn of Texas, locked in his own tight re-election race, recently told the local media that he, too, has disagreed with Mr. Trump on numerous issues, including deficit spending, trade policy and his raiding of the defense budget. Mr. Cornyn said he opted to keep his opposition private rather than get into a public tiff with Mr. Trump “because, as I’ve observed, those usually don’t end too well.” In Alysson Muotri’s laboratory, hundreds of miniature human brains, the size of sesame seeds, float in Petri dishes, sparking with electrical activity. These tiny structures, known as brain organoids, are grown from human stem cells and have become a familiar fixture in many labs that study the properties of the brain. Muotri, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), has found some unusual ways to deploy his. He has connected organoids to walking robots, modified their genomes with Neanderthal genes, launched them into orbit aboard the International Space Station, and used them as models to develop more human-like artificial-intelligence systems. Like many scientists, Muotri has temporarily pivoted to studying COVID-19, using brain organoids to test

In Alysson Muotri’s laboratory, hundreds of miniature human brains, the size of sesame seeds, float in Petri dishes, sparking with electrical activity. These tiny structures, known as brain organoids, are grown from human stem cells and have become a familiar fixture in many labs that study the properties of the brain. Muotri, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), has found some unusual ways to deploy his. He has connected organoids to walking robots, modified their genomes with Neanderthal genes, launched them into orbit aboard the International Space Station, and used them as models to develop more human-like artificial-intelligence systems. Like many scientists, Muotri has temporarily pivoted to studying COVID-19, using brain organoids to test