Category: Recommended Reading

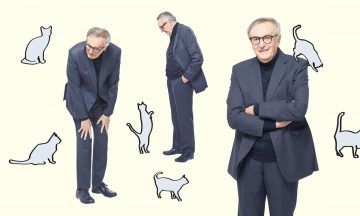

‘What can we learn from cats? Don’t live in an imagined future’

Tim Adams in The Guardian:

What’s it like to be a cat? John Gray has spent a lifetime half-wondering. The philosopher – to his many fans the intellectual cat’s pyjamas, to his critics the least palatable of furballs – has had feline companions at home since he was a boy in South Shields. In adult life – he now lives in Bath with his wife Mieko, a dealer in Japanese antiquities – this has principally been two pairs of cats: “Two Burmese sisters, Sophie and Sarah, and two Birman brothers, Jamie and Julian.” The last of them, Julian, died earlier this year, aged 23. Gray, currently catless, is by no means a sentimental writer, but his new book, Feline Philosophy: Cats and the Meaning of Life, is written in memory of their shared wisdom.

What’s it like to be a cat? John Gray has spent a lifetime half-wondering. The philosopher – to his many fans the intellectual cat’s pyjamas, to his critics the least palatable of furballs – has had feline companions at home since he was a boy in South Shields. In adult life – he now lives in Bath with his wife Mieko, a dealer in Japanese antiquities – this has principally been two pairs of cats: “Two Burmese sisters, Sophie and Sarah, and two Birman brothers, Jamie and Julian.” The last of them, Julian, died earlier this year, aged 23. Gray, currently catless, is by no means a sentimental writer, but his new book, Feline Philosophy: Cats and the Meaning of Life, is written in memory of their shared wisdom.

Other philosophers have been enthralled by cats over the years. There was Schrödinger and his box, of course. And Michel de Montaigne, who famously asked: “When I am playing with my cat, how do I know she is not playing with me?” The rationalist René Descartes, Gray notes, once “hurled a cat out of the window in order to demonstrate the absence of conscious awareness in non-human animals; its terrified screams were mechanical reactions, he concluded.” One impulse for this book was a conversation with a fellow philosopher, who assured Gray that he “had taught his cat to be vegan”. (Gray had only one question: “Did the cat ever go out?” It did.) When he informed another philosopher that he was writing about what we can learn from cats, that man replied: “But cats have no history.” “And,” Gray wondered, “is that necessarily a disadvantage?”

Elsewhere, Gray has written how Ludwig Wittgenstein once observed “if lions could talk we would not understand”, to which the zookeeper John Aspinall responded: “He hasn’t spent long enough with lions.” If cats could talk, I ask Gray, do you think we would understand?

More here.

Spencer Davis (1939 – 2020)

Sunday Poem

All the Questions

When you step through

the back door

into the kitchen

father is still

sitting at the table

with a newspaper

folded open

in front of him

and pen raised, working

the crossword puzzle.

In the living room

mother is sleeping

her peaceful sleep

at last, in a purple

robe, with her head

back, slippered feet

up and twisted

knuckle hands crossed

right over left

in her lap.

Through the south window

in your old room

you see leaves

on the giant ash tree

turning yellow again

in setting sun

and falling slowly

to the ground and one

by one all the questions

you ever had become clear.

Number one across:

a four-letter word

for no longer.

Number one down:

an eleven letter word

for gone.

by Ted Kooser

from American Life in Poetry, 2017

Saturday, October 24, 2020

The Myth of Meritocracy

Timothy Larsen over at the LARB:

Timothy Larsen over at the LARB:

Peter Mandler’s truly impressive study, The Crisis of the Meritocracy: Britain’s Transition to Mass Education since the Second World War, is a deeply researched account of secondary and higher education in Britain during the last seventy-five years. Along the way, it raises and explores some of the largest questions that one can ask about the provision of education: what is it for?; who is it for?; and what subjects should students be studying? As a People’s History, The Crisis of Meritocracy is a tour de force of revisionist insight – slaying assumptions and myths of both the political left and right by keeping its focus fixed on the wishes and actions of young people and their parents. Every claim is advanced with painstaking precision regarding the particular place, time period, percentages, exceptions, and so on. Indeed, the last 134 pages are all scholarly apparatus, beginning with seventeen tables and charts. All this meticulousness has the effect of making a reviewer feel guilty about mining this volume for big-picture discussion points applicable to other nations. It feels a bit like being a tabloid journalist distilling a technical study for crass coverage: “Mandler Manhandles Meritocratic Muddle.” Nevertheless, it is worth the risk, as Mandler’s significant, original, and thought-provoking findings will help us think more clearly about education today, not only in Britain, but also in the United States and elsewhere.

More here.

China’s dollar pragmatism

Kathleen Tyson over at the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum:

Kathleen Tyson over at the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum:

Speculation about the dollar’s hegemonic decline is premature. The global financial plumbing is relatively inflexible in the short term. It will not change quickly or inexpensively.

It took a century of New York banks’ financial activism and extensive global interbank innovation and collaboration to make the dollar a global hegemonic currency.

Dollarisation of the global economy was driven by mercantile ambitions from New York, not geo-strategic ambitions from Washington. New York banks expanded abroad with gold as the hegemonic asset for settlements, offering dollar finance only for trade. The dollar only became a hegemonic currency after the US revoked Bretton Woods dollar-for-gold convertibility in 1971.

It was New York banks that insisted on the need for a central bank and the plumbing for international settlements. The Federal Reserve was founded in 1913 against a backdrop of wider national suspicion and American isolationism, hence the 12 regional reserve banks and a strict domestic mandate. The McFadden Act in 1927 banned inter-state branching and mergers by American banks, forcing New York banks to look abroad for investment and expansion opportunities. Like the Fed, the Bank for International Settlements was conceived in New York to make settlements of gold and German war reparations more convenient. The first two presidents of the BIS were New York mercantile bankers. The Fed only joined the BIS as a member in 1994.

More here.

Ad Tech Could Be the Next Internet Bubble

Gilad Edelman in Wired:

Gilad Edelman in Wired:

WE LIVE IN an age of manipulation. An extensive network of commercial surveillance tracks our every move and a fair number of our thoughts. That data is fed into sophisticated artificial intelligence and used by advertisers to hit us with just the right sales pitch, at just the right time, to get us to buy a toothbrush or sign up for a meal kit or donate to a campaign. The technique is called behavioral advertising, and it raises the frightening prospect that we’ve been made the subjects of a highly personalized form of mind control.

Or maybe that fear is precisely backwards. The real trouble with digital advertising, argues former Google employee Tim Hwang—and the more immediate danger to our way of life—is that it doesn’t work.

Hwang’s new book, Subprime Attention Crisis, lays out the case that the new ad business is built on a fiction. Microtargeting is far less accurate, and far less persuasive, than it’s made out to be, he says, and yet it remains the foundation of the modern internet: the source of wealth for some of the world’s biggest, most important companies, and the mechanism by which almost every “free” website or app makes money. If that shaky foundation ever were to crumble, there’s no telling how much of the wider economy would go down with it.

More here.

Data as Property?

Salomé Viljoen in Phenomenal World:

Salomé Viljoen in Phenomenal World:

Since the proliferation of the World Wide Web in the 1990s, critics of widely used internet communications services have warned of the misuse of personal data. Alongside familiar concerns regarding user privacy and state surveillance, a now-decades-long thread connects a group of theorists who view data—and in particular data about people—as central to what they have termed informational capitalism. Critics locate in datafication—the transformation of information into commodity—a particular economic process of value creation that demarcates informational capitalism from its predecessors. Whether these critics take “information” or “capitalism” as the modifier warranting primary concern, datafication, in their analysis, serves a dual role: both a process of production and a form of injustice.

In arguments levied against informational capitalism, the creation, collection, and use of data feature prominently as an unjust way to order productive activity. For instance, in her 2019 blockbuster The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Shoshanna Zuboff likens our inner lives to a pre-Colonial continent, invaded and strip-mined of data by technology companies seeking profits. Elsewhere, Jathan Sadowski identifies data as a distinct form of capital, and accordingly links the imperative to collect data to the perpetual cycle of capital accumulation. Julie Cohen, in the Polanyian tradition, traces the “quasi-ownership through enclosure” of data and identifies the processing of personal information in “data refineries” as a fourth factor of production under informational capitalism.

Critiques breed proposals for reform. Thus, data governance emerges as key terrain on which to discipline firms engaged in datafication and to respond to the injustices of informational capitalism.

More here.

Hocus-Pocus? Debating the Age of Magic Money

Raphaële Chappe and Mark Blyth debate Sebastian Mallaby in Foreign Affairs (registration required):

Raphaële Chappe and Mark Blyth debate Sebastian Mallaby in Foreign Affairs (registration required):

The COVID-19 recession has prompted states to offer vast amounts of financial support to firms and households. When combined with steps that central banks have taken in response to the financial crisis of 2008, the bailout is so large that it has ushered in what Sebastian Mallaby, writing in the July/August 2020 issue of Foreign Affairs, calls “the age of magic money.” The combination of negative interest rates and low inflation, Mallaby writes, has created a world in which “don’t tax, just spend” makes for a surprisingly sustainable fiscal policy.

The thrust of that description is accurate. But the world Mallaby describes is not a direct result of responses to the financial crisis and the pandemic, as he contends. Nor should it come as much of a surprise.

The roots of the current moment lie in the late 1990s, when the U.S. Federal Reserve responded to the collapse of a major hedge fund by cutting interest rates in an effort to help financial markets avoid more widespread losses.

More here.

Hilary Mantel: Inside the Head of Thomas Cromwell

The Selected Letters of John Berryman

One might expect a person to feel contented after such triumphs. Not so for Berryman. “You were right abt the Pulitzer, and I was wrong,” he wrote publisher Robert Giroux in June 1965. “It doesn’t matter a straw.”

more here.

‘Mantel Pieces’ by Hilary Mantel

Elizabeth Lowry at The Guardian:

When Hilary Mantel first began to write for the London Review of Books in 1987 she warned the editor that she had “no critical training whatsoever”. “Thank goodness,” you think. What Mantel has instead are much more useful qualities: a researcher’s in-depth grasp of every topic she writes about, fearlessness, originality and robust common sense. Her wide-ranging pieces, spanning three decades, are the best kind of critical writing, rich with recondite knowledge, wearing their learning lightly.

When Hilary Mantel first began to write for the London Review of Books in 1987 she warned the editor that she had “no critical training whatsoever”. “Thank goodness,” you think. What Mantel has instead are much more useful qualities: a researcher’s in-depth grasp of every topic she writes about, fearlessness, originality and robust common sense. Her wide-ranging pieces, spanning three decades, are the best kind of critical writing, rich with recondite knowledge, wearing their learning lightly.

The essays in this collection explore subjects – France’s ancien régime and the revolution, Tudor England and the court of Henry VIII, illness and the body, spiritualism and visionary experience – that the double Booker winner has made her own in her fiction and her memoir, Giving Up the Ghost (2003). What sets Mantel’s novels apart is also what sets her critical writing apart: an unerring eye for the telling detail, the clue that will unlock what she calls “the puzzle of personal identity”.

more here.

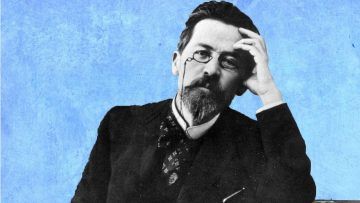

Poet of Loneliness

Gary Saul Morson in First Things:

No writer understood loneliness better than Chekhov. People long for understanding, and try to confide their feelings, but more often than not, others are too self-absorbed to care. In Chekhov’s plays, unlike those of his predecessors, characters speak past each other. Often enough, they talk in turn, but do not converse. Dunyasha, the maid in The Cherry Orchard, is eager to tell Anya, who has just arrived from abroad, that the clerk Yepikhodov proposed to her. Anya is too absorbed in her own memories to listen.

No writer understood loneliness better than Chekhov. People long for understanding, and try to confide their feelings, but more often than not, others are too self-absorbed to care. In Chekhov’s plays, unlike those of his predecessors, characters speak past each other. Often enough, they talk in turn, but do not converse. Dunyasha, the maid in The Cherry Orchard, is eager to tell Anya, who has just arrived from abroad, that the clerk Yepikhodov proposed to her. Anya is too absorbed in her own memories to listen.

Dunyasha: I’ve waited for you, my joy, my precious . . . I must tell you at once, I can’t wait another minute . . .

Anya: [listlessly] What?

Dunyasha: The clerk, Yepikhodov, proposed to me just after Easter.

Anya: You always talk about the same thing. . . . [Straightening her hair]. I’ve lost all my hairpins . . .

Dunyasha: I really don’t know what to think. He loves me—he loves me so!

Anya: [looking through the door into her room, tenderly] My, room, my windows. . . . I am home!

Chekhov’s audience cannot help thinking: If only we would enter into the feelings of others, life would be so much better.

In one early story, written before Chekhov imagined he could ever be a serious author, a cabman, Iona, tries time and time again to tell each of his fares about the death of his son, but everyone is in a hurry and no one pays any attention. He longs to share his grief, but he returns his horse to the stable as lonely as before. As the story ends, he at last addresses someone who appears to listen: his horse. “That’s how it is old girl,” he explains. “He went and died for no reason. . . .

Now suppose, you had a little colt, and you were own mother to that little colt. . . . And all at once that same little colt went and died. . . . You’d be sorry, wouldn’t you?” The story ends: “The little mare munches, listens, and breathes on her master’s hands. Iona is carried away and tells her all about it.”

More here.

Saturday Poem

The Right Word

The right word

Outside the door,

lurking in the shadows,

is a terrorist.

Is that the wrong description?

Outside that door,

taking shelter in the shadows,

is a freedom fighter.

I haven’t got this right.

Outside, waiting in the shadows,

is a hostile militant.

Are words no more

than waving, wavering flags?

Outside your door,

watchful in the shadows,

is a guerrilla warrior.

God help me.

Outside, defying every shadow,

stands a martyr.

I saw his face.

No words can help me now.

Just outside the door,

lost in shadows,

is a child who looks like mine.

One word for you.

Outside my door,

his hand too steady,

his eyes too hard

is a boy who looks like your son, too.

I open the door.

Come in, I say.

Come in and eat with us.

The child steps in

and carefully, at my door,

takes off his shoes.

by Imtiaz Dharker

from The Terrorist at My Table

publisher: Bloodaxe, 2006

What Can You Do If Trump Stages a Coup?

Lizzie Widdicombe in The New Yorker:

Ah, election season. There’s a patriotic buzz in the air. Bumper stickers and lawn signs all over the neighborhood. Now comes the time when we check the location of our polling places, make a plan to vote—and pack a “go bag” in case we need to take to the streets in sustained mass protest to protect the integrity of the vote count. That last one is not something you’d expect to be doing in the United States, but things are different in the Trump era. For months, the President has been warning that he might not concede the election in November if he loses, telling reporters who asked him to commit to a peaceful transfer of power, “There won’t be a transfer, frankly. There’ll be a continuation.” It sounded ominous, although it was hard to imagine how he could make good on the threat to stick around no matter what. Then, media organizations began publishing pieces outlining the myriad ways in which the President and his allies might turn a narrow loss into a win. The possibilities include familiar tactics—contesting mail-in ballots and turning the process into Bush v. Gore on steroids—and others that sound straight out of a police state. For example, Trump could summon federal agents or his supporters to stop a recount or intimidate voters. According to some experts, this would constitute an autogolpe, or “self coup”: when a President who obtained power through constitutional means holds onto it through illegitimate ones, beginning the slide into authoritarianism.

Ah, election season. There’s a patriotic buzz in the air. Bumper stickers and lawn signs all over the neighborhood. Now comes the time when we check the location of our polling places, make a plan to vote—and pack a “go bag” in case we need to take to the streets in sustained mass protest to protect the integrity of the vote count. That last one is not something you’d expect to be doing in the United States, but things are different in the Trump era. For months, the President has been warning that he might not concede the election in November if he loses, telling reporters who asked him to commit to a peaceful transfer of power, “There won’t be a transfer, frankly. There’ll be a continuation.” It sounded ominous, although it was hard to imagine how he could make good on the threat to stick around no matter what. Then, media organizations began publishing pieces outlining the myriad ways in which the President and his allies might turn a narrow loss into a win. The possibilities include familiar tactics—contesting mail-in ballots and turning the process into Bush v. Gore on steroids—and others that sound straight out of a police state. For example, Trump could summon federal agents or his supporters to stop a recount or intimidate voters. According to some experts, this would constitute an autogolpe, or “self coup”: when a President who obtained power through constitutional means holds onto it through illegitimate ones, beginning the slide into authoritarianism.

O.K., then. Time to start getting ready. But how, exactly, do we do that? In September, a group of organizers and researchers published a fifty-five-page manual called “Hold the Line: A Guide to Defending Democracy,” which has been downloaded more than eighteen thousand times. And the Indivisible Project, along with a coalition called Stand Up America, are preparing their members to take to the streets if Trump contests the election results. “I’ve been beating the drum on this particular cause since July, and I’m delighted to see so many people coming around to it,” the activist and sociologist George Lakey said recently. His own “Aha!” moment came when Trump sent federal agents in military fatigues to Portland, Oregon, to tangle with protesters. “It hit me, the way Trump is dealing with Portland, Oregon, that’s a test,” he said. He guessed that Trump was hoping to provoke a violent backlash from the protesters, so that he could lay the groundwork for not accepting the election results, under the pretense that the country had descended into violent chaos. “Trump can be underestimated by the left,” Lakey said. “He gets made fun of, but he’s shrewd.”

More here.

Friday, October 23, 2020

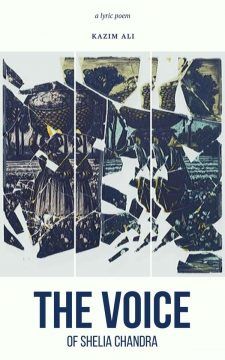

A review of Kazim Ali’s latest book of poems

Jeevika Verma at NPR:

Kazim Ali’s latest book of poems is born out of our collective existential crisis. How do we continue to survive “in a world governed by storm and noise”? Creating an ingenious form on the page, Ali uses sound to give us a sort of research project that grapples with this crisis of survival over time. But the project’s beauty manifests from the impossibility of its findings. After all, how is one supposed to answer the colossal question of existence?

Kazim Ali’s latest book of poems is born out of our collective existential crisis. How do we continue to survive “in a world governed by storm and noise”? Creating an ingenious form on the page, Ali uses sound to give us a sort of research project that grapples with this crisis of survival over time. But the project’s beauty manifests from the impossibility of its findings. After all, how is one supposed to answer the colossal question of existence?

Ali, who is an accomplished translator, editor, and teacher, takes on this task by going beyond our understanding of language. As such, with three long poems strung together by four short ones, the collection is a form in itself, complete in its sequential innovation. It is intentional in its intricacy as it seeps through the pages and transcends something that can be contained.

Throughout The Voice of Sheila Chandra, Ali grabs fragments of stories to depict the ways we study our past, realize our survival, and move into the next sequence.

More here.

Could Fracking Actually Help the Climate?

Zeke Hausfather and Alex Trembath in Politico:

Hydraulic fracturing — the controversial oil and gas extraction method usually called “fracking” — has divided Democrats and the political left for a decade now. Many in the environmental community claim that allowing fracking is incompatible with climate action. Others, including Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, take a more nuanced position: During their respective debates, both Biden and Harris emphasized that a Biden-Harris administration would not ban fracking.

Hydraulic fracturing — the controversial oil and gas extraction method usually called “fracking” — has divided Democrats and the political left for a decade now. Many in the environmental community claim that allowing fracking is incompatible with climate action. Others, including Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, take a more nuanced position: During their respective debates, both Biden and Harris emphasized that a Biden-Harris administration would not ban fracking.

While most environmental groups tend to be on the side of a ban, there are actually strong environmental justifications for Biden and Harris’s light touch on fracking today. In fact, there are reasons to worry that even a partial ban on fracking could slow decarbonization efforts in the near-term. What’s more, the deployment of some clean energy technologies could depend, perhaps counterintuitively, on fracking.

More here.

Are the Police Systemically Racist?

Phillip Meylan in The Factual:

From Jacob Blake, to George Floyd, to Breonna Taylor, 2020 has seen immense pressure to re-examine how the police interact with society. The oft-cited statistic that Black individuals are several times more likely to be shot during police interactions has come under intense scrutiny as a result. While the generalized viewpoint on the left is that this is evidence of systemic racism, skeptics on the right counter that this is a result of Black people being responsible for a disproportionate amount of violent crime, not systemic racism in the police. At the same time, there’s an increasing number of voices on the right that acknowledge the existence of systemic racism in policing, marking a shift in attitudes since the killing of Michael Brown and the national emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2014.

From Jacob Blake, to George Floyd, to Breonna Taylor, 2020 has seen immense pressure to re-examine how the police interact with society. The oft-cited statistic that Black individuals are several times more likely to be shot during police interactions has come under intense scrutiny as a result. While the generalized viewpoint on the left is that this is evidence of systemic racism, skeptics on the right counter that this is a result of Black people being responsible for a disproportionate amount of violent crime, not systemic racism in the police. At the same time, there’s an increasing number of voices on the right that acknowledge the existence of systemic racism in policing, marking a shift in attitudes since the killing of Michael Brown and the national emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2014.

This week, The Factual set out to survey how the media has covered the issue of systemic racism in the police, from its definition, to the evidence of its existence, to its skeptics, to the steps necessary to better understand the issue and how to address it.

More here.

Salman Rushdie’s statement regarding the upcoming election

The Lesbian Partnership That Changed Literature

Emma Garman in The Paris Review:

In the early thirties, for a certain clique of Left Bank–dwelling American lesbians, the place to be was not an expat haunt like the Café de Flore or Le Deux Magots. Nor was it Le Monocle, the wildly popular nightclub owned by tuxedoed butch Lulu du Montparnasse and named for the accessory worn to signal one’s orientation. According to the writer Solita Solano, the “only important thing in Paris” was a study group on the philosophies of the Greek-Armenian mystic George Ivanovich Gurdjieff, held at Jane Heap’s apartment. Heap, a Kansas-born artist, writer, and gallerist, was Gurdjieff’s official emissary, a rare honor. Under her supervision, the group engaged in intense self-revelation, narrating the stories of their lives without censoring or embellishing. As the author Kathryn Hulme explained in her memoir, Undiscovered Country: A Spiritual Adventure, the goal was to uncover the real I and thus escape being “a helpless slave to circumstances, to whatever chameleon personality took the initiative.”

In the early thirties, for a certain clique of Left Bank–dwelling American lesbians, the place to be was not an expat haunt like the Café de Flore or Le Deux Magots. Nor was it Le Monocle, the wildly popular nightclub owned by tuxedoed butch Lulu du Montparnasse and named for the accessory worn to signal one’s orientation. According to the writer Solita Solano, the “only important thing in Paris” was a study group on the philosophies of the Greek-Armenian mystic George Ivanovich Gurdjieff, held at Jane Heap’s apartment. Heap, a Kansas-born artist, writer, and gallerist, was Gurdjieff’s official emissary, a rare honor. Under her supervision, the group engaged in intense self-revelation, narrating the stories of their lives without censoring or embellishing. As the author Kathryn Hulme explained in her memoir, Undiscovered Country: A Spiritual Adventure, the goal was to uncover the real I and thus escape being “a helpless slave to circumstances, to whatever chameleon personality took the initiative.”

Among those who gathered in Heap’s small sitting room were Janet Flanner, the New Yorker Paris correspondent and Solano’s lifelong partner; the journalist and author Djuna Barnes; and the actress Louise Davidson. One attendee, Hulme noted, would enter the room “like a Valkyrie” and “knew how to load the questions she fired at Jane, how to bait her to reveal more than perhaps was intended for beginners.” The Valkyrie was Margaret Caroline Anderson, founder of the trailblazing Little Review, with whom Heap had first encountered Gurdjieff in New York in the early twenties. Heap and Anderson, whose friendship outlasted a love affair and a professional partnership, were kindred geniuses with an exclusive affinity. When Barnes, after a fling with Heap, marveled at her “deep personal madness,” Anderson replied: “Deep personal knowledge—a supreme sanity.” Heap called Anderson “my blessed antagonistic complement.” Via their shared endeavors and the cross-pollination of their ideas—artistic, literary, and spiritual—these two remarkable women left an indelible imprint on avant-garde culture between the wars.

More here.

“I have a crazy new way of writing poems,” John Berryman wrote to illustrator Ben Shahn in January 1956. He had indeed hit on something crazy and new: an 18-line structure he ended up calling his “

“I have a crazy new way of writing poems,” John Berryman wrote to illustrator Ben Shahn in January 1956. He had indeed hit on something crazy and new: an 18-line structure he ended up calling his “