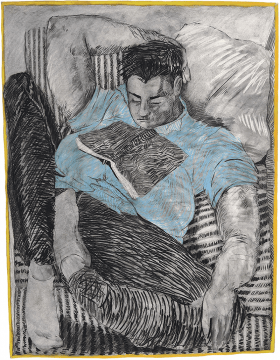

Garth Greenwell in Harper’s:

The word “relevant,” I was recently surprised to discover, shares an etymology with the word “relieve.” This seems obvious enough once you know it—only a few letters separate the words—but their usages diverged so long ago that I had never associated them before. Searching out etymologies is an old habit, picked up in the decades when I aspired to be a poet. Language is fossil poetry, Emerson says, and the poem the Oxford English Dictionary lays out in this case is remarkably moving. The common forebear of both “relevant” and “relieve” is the French relever, which meant, originally, to put back into an upright position, to raise again, a word that twisted through time, scattering meanings that our two modern words have apportioned between them: to ease pain or discomfort, to make stand out, to render prominent or distinct, to rise up or rebel, to rebuild, to reinvigorate, to make higher, to set free.

The word “relevant,” I was recently surprised to discover, shares an etymology with the word “relieve.” This seems obvious enough once you know it—only a few letters separate the words—but their usages diverged so long ago that I had never associated them before. Searching out etymologies is an old habit, picked up in the decades when I aspired to be a poet. Language is fossil poetry, Emerson says, and the poem the Oxford English Dictionary lays out in this case is remarkably moving. The common forebear of both “relevant” and “relieve” is the French relever, which meant, originally, to put back into an upright position, to raise again, a word that twisted through time, scattering meanings that our two modern words have apportioned between them: to ease pain or discomfort, to make stand out, to render prominent or distinct, to rise up or rebel, to rebuild, to reinvigorate, to make higher, to set free.

I looked up this history because I realized that somehow I’d lost my sense of what we mean when we talk about “relevance,” especially the relevance of art, and I wanted to know whether the problem lay in my own understanding or in some deficiency in our usage. The word is everywhere in blurbs and reviews as a quality to admire or, more than that, as a necessary condition; “irrelevant” has joined “problematic” as a term of absolute dismissal, applied not so much to books one reads and hotly debates as to books one needn’t read at all. Artists feel the anxiety of relevance during every season of fellowship applications, those rituals of supplication, when we have to make a case for ourselves in a way that feels entirely foreign, for me at least, to the real motivations of art. Why is this the right project for this moment? these applications often ask. If I had a question like that on my mind as I tried to make art, I would never write another word. This pressure has only increased in recent years. I can still remember the shudder I felt in early 2017 when, after expressing my desire to review a newly translated European novel, an editor asked me to find “a Trump angle” to make the book relevant to his magazine’s readers. There’s something demeaning about approaching art from a predetermined angle, all the more so when that angle is determined by our current president.

More here.

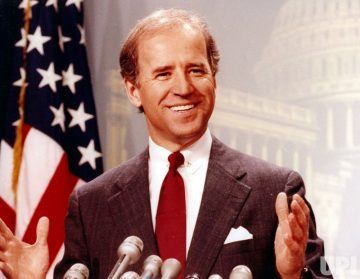

When every legally cast vote has been counted, Joe Biden will probably have prevailed in enough states to claim victory in the presidential race, perhaps even ending up with a few more Electoral Votes than Donald Trump managed to earn four years ago. That means Trump will probably be out, defeated in his bid for re-election.

When every legally cast vote has been counted, Joe Biden will probably have prevailed in enough states to claim victory in the presidential race, perhaps even ending up with a few more Electoral Votes than Donald Trump managed to earn four years ago. That means Trump will probably be out, defeated in his bid for re-election.

Karachi ranks as having the worst public transport system globally, according to

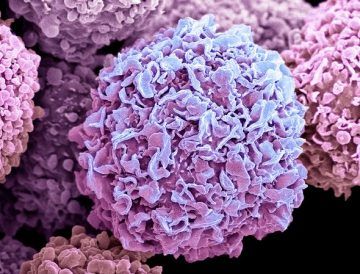

Karachi ranks as having the worst public transport system globally, according to  Improving early cancer detection may be the only way to really put a dent in the cancer mortality curve; however, early cancer detection is suffering from a common ailment in medicine and public health: the streetlight effect. We are looking for five cancers “over here” under the streetlight where we have early detection tests, but about

Improving early cancer detection may be the only way to really put a dent in the cancer mortality curve; however, early cancer detection is suffering from a common ailment in medicine and public health: the streetlight effect. We are looking for five cancers “over here” under the streetlight where we have early detection tests, but about  “SENESCENCE” ISN’T QUITE THE RIGHT WORD for the stage the writers of the Baby Boom have reached. Sure, they may be collecting social security, the eldest of them in their mid-seventies, but the wonders of modern science may allow some another couple of decades of productivity. When the Reaper starts to come for the writer’s instrument, the first thing to go is flow, but that may not matter: fragments are in. In a decade or so, robbed of their transitions and reduced to accumulating prose shards, the octogenarian Boomers may find themselves newly trendy. A strange fate for a generation that entered the literary world at the height of its postmodern excesses: everyone still standing will turn into Lydia Davis.

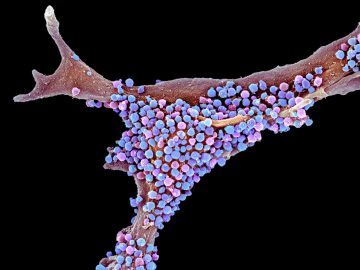

“SENESCENCE” ISN’T QUITE THE RIGHT WORD for the stage the writers of the Baby Boom have reached. Sure, they may be collecting social security, the eldest of them in their mid-seventies, but the wonders of modern science may allow some another couple of decades of productivity. When the Reaper starts to come for the writer’s instrument, the first thing to go is flow, but that may not matter: fragments are in. In a decade or so, robbed of their transitions and reduced to accumulating prose shards, the octogenarian Boomers may find themselves newly trendy. A strange fate for a generation that entered the literary world at the height of its postmodern excesses: everyone still standing will turn into Lydia Davis. Two years ago, immunologist and medical-publishing entrepreneur Leslie Norins offered to award US$1 million of his own money to any scientist who could prove that Alzheimer’s disease was caused by a germ. The theory that an infection might cause this form of dementia has been rumbling for decades on the fringes of neuroscience research. The majority of Alzheimer’s researchers, backed by a huge volume of evidence, think instead that the key culprits are sticky molecules in the brain called amyloids, which clump into plaques and cause inflammation, killing neurons. Norins wanted to reward work that would make the infection idea more persuasive. The amyloid hypothesis has become “the one acceptable and supportable belief of the Established Church of Conventional Wisdom”, says Norins. “The few pioneers who did look at microbes and published papers were ridiculed or ignored.”

Two years ago, immunologist and medical-publishing entrepreneur Leslie Norins offered to award US$1 million of his own money to any scientist who could prove that Alzheimer’s disease was caused by a germ. The theory that an infection might cause this form of dementia has been rumbling for decades on the fringes of neuroscience research. The majority of Alzheimer’s researchers, backed by a huge volume of evidence, think instead that the key culprits are sticky molecules in the brain called amyloids, which clump into plaques and cause inflammation, killing neurons. Norins wanted to reward work that would make the infection idea more persuasive. The amyloid hypothesis has become “the one acceptable and supportable belief of the Established Church of Conventional Wisdom”, says Norins. “The few pioneers who did look at microbes and published papers were ridiculed or ignored.” In their heyday, the communists were the most political and most intentional of people. That made them often the most terrifying of people, capable of violence on an unimaginable scale. Yet despite—and perhaps also because of—their ruthless sense of purpose, communism contains many lessons for us today. As a new generation of socialists, most born after the Cold War, discovers the challenges of parties and movements and the implications of involvement, the archive of communism, particularly American communism, has become newly relevant. So have two commentaries on that archive: Vivian Gornick’s The Romance of American Communism, originally published in 1977 and reissued this year, and Jodi Dean’s Comrade: An Essay on Political Belonging.

In their heyday, the communists were the most political and most intentional of people. That made them often the most terrifying of people, capable of violence on an unimaginable scale. Yet despite—and perhaps also because of—their ruthless sense of purpose, communism contains many lessons for us today. As a new generation of socialists, most born after the Cold War, discovers the challenges of parties and movements and the implications of involvement, the archive of communism, particularly American communism, has become newly relevant. So have two commentaries on that archive: Vivian Gornick’s The Romance of American Communism, originally published in 1977 and reissued this year, and Jodi Dean’s Comrade: An Essay on Political Belonging. Immanuel Kant, who smoked a pipe of tobacco with his tea once or twice a day, described the aesthetic category of the sublime as a “negative pleasure”: “incompatible with charms,” as “the mind is not just attracted by the object but is alternately always repelled as well.” Not unlike the feeling of respect, sublimity is greeted by the Kantian subject with a manic combination of satisfaction and fear, a sense of pride in the superiority of human intellect at the expense of imaginative and physical fallibility. A frisson of euphoria and disgust, or as Richard Klein writes in Cigarettes Are Sublime, “a darkly beautiful, inevitably painful pleasure that arises from some intimation of eternity.” The “taste of infinity in a cigarette” presents to the smoker a philosophical “edge of the abyss”: mortality, selfhood, existence. For Annie Leclerc, in Au feu du jour, “the cigarette is the prayer of our time.”

Immanuel Kant, who smoked a pipe of tobacco with his tea once or twice a day, described the aesthetic category of the sublime as a “negative pleasure”: “incompatible with charms,” as “the mind is not just attracted by the object but is alternately always repelled as well.” Not unlike the feeling of respect, sublimity is greeted by the Kantian subject with a manic combination of satisfaction and fear, a sense of pride in the superiority of human intellect at the expense of imaginative and physical fallibility. A frisson of euphoria and disgust, or as Richard Klein writes in Cigarettes Are Sublime, “a darkly beautiful, inevitably painful pleasure that arises from some intimation of eternity.” The “taste of infinity in a cigarette” presents to the smoker a philosophical “edge of the abyss”: mortality, selfhood, existence. For Annie Leclerc, in Au feu du jour, “the cigarette is the prayer of our time.” To fixate on the question of Q’s identity would be, in the conspiracist’s parlance, to chase a false flag. And a group curiously close to Q would likely say the same: the leftist Italian literary collective Wu Ming, a pseudonym translating to “anonymous” or “no name,” which was formed in 2000 as an outgrowth of Luther Blissett, a nom de plume for the same circle of coauthors. In 1999, Blissett published Q, a historical-adventure novel set during the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation that follows an anonymous Anabaptist radical as he is pursued around Europe by Q, a Roman Catholic spy. In a December 2002 essay posted to its website, Wu Ming declared, “We are interested in ﹡mythopoesis﹡, i.e. the social process of constructing myths, by which we do not mean ‘false stories,’ we mean stories that are told and shared, re-told and manipulated, by a vast and multifarious community, stories that may give shape to some kind of ritual, some sense of continuity between what we do and what other people did in the past. A tradition.” This sounds uncannily similar to QAnon’s story for the people. Q often claims that “Future proves past,” setting its readers up to understand time as a circular process, and, in a sense, it’s not wrong. Time ceases to be progressive in Q’s realm, and on the world stage, ancient crimes and sins are eternally recurring eruptions that must be quashed anew by righteous armies in recycled costumery. Anyone with a taste for devotion and a capacity for faith is a potential conscript. Someone, somewhere, is laughing their head off at their joke, having inflamed all sides in a war for what’s true and who’s accountable for it. No need to bother with guillotines when heads are already lost. And here fall the rest of us down rabbit holes that never end, while others await the longed-for storm, not realizing they have drowned beneath its waves.

To fixate on the question of Q’s identity would be, in the conspiracist’s parlance, to chase a false flag. And a group curiously close to Q would likely say the same: the leftist Italian literary collective Wu Ming, a pseudonym translating to “anonymous” or “no name,” which was formed in 2000 as an outgrowth of Luther Blissett, a nom de plume for the same circle of coauthors. In 1999, Blissett published Q, a historical-adventure novel set during the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation that follows an anonymous Anabaptist radical as he is pursued around Europe by Q, a Roman Catholic spy. In a December 2002 essay posted to its website, Wu Ming declared, “We are interested in ﹡mythopoesis﹡, i.e. the social process of constructing myths, by which we do not mean ‘false stories,’ we mean stories that are told and shared, re-told and manipulated, by a vast and multifarious community, stories that may give shape to some kind of ritual, some sense of continuity between what we do and what other people did in the past. A tradition.” This sounds uncannily similar to QAnon’s story for the people. Q often claims that “Future proves past,” setting its readers up to understand time as a circular process, and, in a sense, it’s not wrong. Time ceases to be progressive in Q’s realm, and on the world stage, ancient crimes and sins are eternally recurring eruptions that must be quashed anew by righteous armies in recycled costumery. Anyone with a taste for devotion and a capacity for faith is a potential conscript. Someone, somewhere, is laughing their head off at their joke, having inflamed all sides in a war for what’s true and who’s accountable for it. No need to bother with guillotines when heads are already lost. And here fall the rest of us down rabbit holes that never end, while others await the longed-for storm, not realizing they have drowned beneath its waves. Burke’s story is ultimately one of decline, from the ‘monsters of erudition’ of the 17th century to the present era of specialisation. Early modernists may feel that he is slightly cheating in his description of their period by setting up as separate disciplines subjects that were always studied together. For example, optics, astronomy and geometry were all part of ‘mathematics’, and it was effectively impossible to specialise in only one of them; in these terms, anyone who practised the subject was a polymath. This being admitted, some figures omitted here seem more worthy of inclusion than others who do appear: for example, the Flemish Simon Stevin made seminal contributions to pure and applied mathematics, as well as engineering, music theory and bookkeeping, while also practising chemistry, among many other disciplines.

Burke’s story is ultimately one of decline, from the ‘monsters of erudition’ of the 17th century to the present era of specialisation. Early modernists may feel that he is slightly cheating in his description of their period by setting up as separate disciplines subjects that were always studied together. For example, optics, astronomy and geometry were all part of ‘mathematics’, and it was effectively impossible to specialise in only one of them; in these terms, anyone who practised the subject was a polymath. This being admitted, some figures omitted here seem more worthy of inclusion than others who do appear: for example, the Flemish Simon Stevin made seminal contributions to pure and applied mathematics, as well as engineering, music theory and bookkeeping, while also practising chemistry, among many other disciplines. Among the many rules for the conduct of life that Pythagoras passed down to members of his philosophical cult, there is a peculiar prohibition that keeps coming up in late-antique testimonia: Consume no lentils. Decline all lupins. Eat not pulses. Abstain from beans. Different authors provide different rationales for this (Diogenes Laërtius says that it is because beans resemble testicles, and perhaps also the gates of Hades), but we may isolate three of them as the most common and most compelling. First, you must not eat beans because they produce within you an undesirable flatus, damaging to your health and noxious to those around you. Second, you must not eat beans for the same reason you must not eat meat — they too are ensouled, and may well harbour the particular souls of your reincarnated love ones.

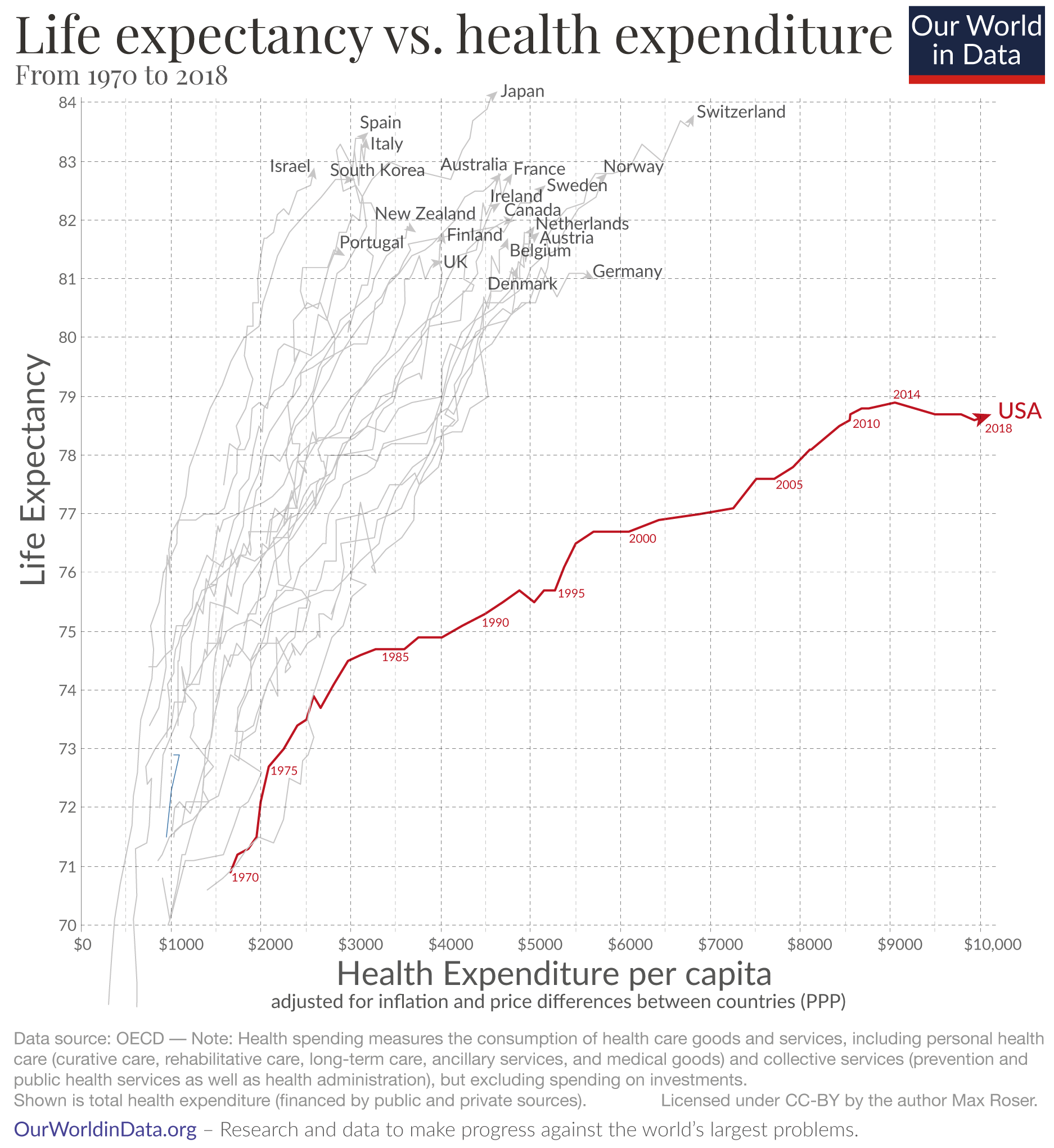

Among the many rules for the conduct of life that Pythagoras passed down to members of his philosophical cult, there is a peculiar prohibition that keeps coming up in late-antique testimonia: Consume no lentils. Decline all lupins. Eat not pulses. Abstain from beans. Different authors provide different rationales for this (Diogenes Laërtius says that it is because beans resemble testicles, and perhaps also the gates of Hades), but we may isolate three of them as the most common and most compelling. First, you must not eat beans because they produce within you an undesirable flatus, damaging to your health and noxious to those around you. Second, you must not eat beans for the same reason you must not eat meat — they too are ensouled, and may well harbour the particular souls of your reincarnated love ones. Why do Americans have a lower life expectancy than people in other rich countries, despite paying so much more for health care?

Why do Americans have a lower life expectancy than people in other rich countries, despite paying so much more for health care? Esa-Pekka Salonen didn’t expect to make his entrance at the San Francisco Symphony with a virtual premiere.

Esa-Pekka Salonen didn’t expect to make his entrance at the San Francisco Symphony with a virtual premiere. The word “relevant,” I was recently surprised to discover, shares an etymology with the word “relieve.” This seems obvious enough once you know it—only a few letters separate the words—but their usages diverged so long ago that I had never associated them before. Searching out etymologies is an old habit, picked up in the decades when I aspired to be a poet. Language is fossil poetry, Emerson says, and the poem the Oxford English Dictionary lays out in this case is remarkably moving. The common forebear of both “relevant” and “relieve” is the French relever, which meant, originally, to put back into an upright position, to raise again, a word that twisted through time, scattering meanings that our two modern words have apportioned between them: to ease pain or discomfort, to make stand out, to render prominent or distinct, to rise up or rebel, to rebuild, to reinvigorate, to make higher, to set free.

The word “relevant,” I was recently surprised to discover, shares an etymology with the word “relieve.” This seems obvious enough once you know it—only a few letters separate the words—but their usages diverged so long ago that I had never associated them before. Searching out etymologies is an old habit, picked up in the decades when I aspired to be a poet. Language is fossil poetry, Emerson says, and the poem the Oxford English Dictionary lays out in this case is remarkably moving. The common forebear of both “relevant” and “relieve” is the French relever, which meant, originally, to put back into an upright position, to raise again, a word that twisted through time, scattering meanings that our two modern words have apportioned between them: to ease pain or discomfort, to make stand out, to render prominent or distinct, to rise up or rebel, to rebuild, to reinvigorate, to make higher, to set free.