Category: Recommended Reading

The Lesbian Partnership That Changed Literature

Emma Garman in The Paris Review:

In the early thirties, for a certain clique of Left Bank–dwelling American lesbians, the place to be was not an expat haunt like the Café de Flore or Le Deux Magots. Nor was it Le Monocle, the wildly popular nightclub owned by tuxedoed butch Lulu du Montparnasse and named for the accessory worn to signal one’s orientation. According to the writer Solita Solano, the “only important thing in Paris” was a study group on the philosophies of the Greek-Armenian mystic George Ivanovich Gurdjieff, held at Jane Heap’s apartment. Heap, a Kansas-born artist, writer, and gallerist, was Gurdjieff’s official emissary, a rare honor. Under her supervision, the group engaged in intense self-revelation, narrating the stories of their lives without censoring or embellishing. As the author Kathryn Hulme explained in her memoir, Undiscovered Country: A Spiritual Adventure, the goal was to uncover the real I and thus escape being “a helpless slave to circumstances, to whatever chameleon personality took the initiative.”

In the early thirties, for a certain clique of Left Bank–dwelling American lesbians, the place to be was not an expat haunt like the Café de Flore or Le Deux Magots. Nor was it Le Monocle, the wildly popular nightclub owned by tuxedoed butch Lulu du Montparnasse and named for the accessory worn to signal one’s orientation. According to the writer Solita Solano, the “only important thing in Paris” was a study group on the philosophies of the Greek-Armenian mystic George Ivanovich Gurdjieff, held at Jane Heap’s apartment. Heap, a Kansas-born artist, writer, and gallerist, was Gurdjieff’s official emissary, a rare honor. Under her supervision, the group engaged in intense self-revelation, narrating the stories of their lives without censoring or embellishing. As the author Kathryn Hulme explained in her memoir, Undiscovered Country: A Spiritual Adventure, the goal was to uncover the real I and thus escape being “a helpless slave to circumstances, to whatever chameleon personality took the initiative.”

Among those who gathered in Heap’s small sitting room were Janet Flanner, the New Yorker Paris correspondent and Solano’s lifelong partner; the journalist and author Djuna Barnes; and the actress Louise Davidson. One attendee, Hulme noted, would enter the room “like a Valkyrie” and “knew how to load the questions she fired at Jane, how to bait her to reveal more than perhaps was intended for beginners.” The Valkyrie was Margaret Caroline Anderson, founder of the trailblazing Little Review, with whom Heap had first encountered Gurdjieff in New York in the early twenties. Heap and Anderson, whose friendship outlasted a love affair and a professional partnership, were kindred geniuses with an exclusive affinity. When Barnes, after a fling with Heap, marveled at her “deep personal madness,” Anderson replied: “Deep personal knowledge—a supreme sanity.” Heap called Anderson “my blessed antagonistic complement.” Via their shared endeavors and the cross-pollination of their ideas—artistic, literary, and spiritual—these two remarkable women left an indelible imprint on avant-garde culture between the wars.

More here.

Body Language

Sanjana Varghese in The Baffler:

IN LINCOLNSHIRE, ENGLAND, the local police force has indicated that they will be testing out a kind of “emotion recognition” technology on CCTV footage which they collect around Gainsborough, a town in the county. Lincolnshire’s police and crime commissioner, Marc Jones, secured funding from the UK Home Office for this project, but the exact system that the police will use, and its exact supplier, are still not confirmed. All that the police force knows is that they want to use it.

It may seem like an overreach for a provincial police force to roll out a nebulous new technology, even the description of which sounds sinister, but I’ve started to think there is a less obvious reason behind their choice. Facial recognition has been the subject of much scrutiny and regulation; in the UK, a man named Ed Bridges took the South Wales Police to court over the use of automated facial recognition and won. But the South Wales Police force has indicated that they will continue to use their system, with the chief constable Matt Jukes saying that he was “confident this is a judgement we can work with.”

More here.

Friday Poem

Canary

—for Michael S. Harper

Billie Holiday’s burned voice

had as many shadows as lights,

a mournful candelabra against a sleek piano,

the gardenia her signature under that ruined face.

(Now you’re cooking, drummer to bass,

magic spoon, magic needle.

Take all day if you have to

With your mirror and your bracelet of song.)

Fact is, the invention of women under siege

has been to sharpen love in the service of myth.

If you can’t be free, be a mystery.

by Rita Dove

from Collected Poems 1974-2004

W. W. Norton & Co., Inc., New York, 2016

ALICE SMITH: Black Mary – A film by KAHLIL JOSEPH

The Merovingians and the Mediterranean

Clifford Backman at berfrois:

When one thinks about the Merovingians—and, really, who doesn’t?—one seldom thinks of the Mediterranean. There is good reason for that. Whatever else the Merovingians may have been, they were a hodgepodge of northern clans, tribes, and kingdoms who came from one end of the northern tier of Europe and settled eventually in the other. They drank beer rather than wine; cooked in lard rather than olive oil; avoided cities as centers of evil spirits; had little literature that we know of and less science; had no ships other than rivercraft; and lived, fought, and died on scattered parcels of farmland cleared from the immense, dense forest of the continent. That is not to say they fitted the prejudiced Dark Age caricature of them as mere “barbarians”—a kind of gruesome but temporary way station between the glories of Rome and Aachen. As shown by a generation of scholars from Walter Goffart and Ian Wood to Chris Wickham, Andreas Fischer, and Peter Heather, the period from Rome’s fall to Aachen’s ascent deserves to be studied for its own self and not merely as another of history’s dreary “periods of transition”; after all, every age is one of transition, and the transitions involved—political, cultural, intellectual, technological, and every other type—are usually themselves the chief points of interest.

When one thinks about the Merovingians—and, really, who doesn’t?—one seldom thinks of the Mediterranean. There is good reason for that. Whatever else the Merovingians may have been, they were a hodgepodge of northern clans, tribes, and kingdoms who came from one end of the northern tier of Europe and settled eventually in the other. They drank beer rather than wine; cooked in lard rather than olive oil; avoided cities as centers of evil spirits; had little literature that we know of and less science; had no ships other than rivercraft; and lived, fought, and died on scattered parcels of farmland cleared from the immense, dense forest of the continent. That is not to say they fitted the prejudiced Dark Age caricature of them as mere “barbarians”—a kind of gruesome but temporary way station between the glories of Rome and Aachen. As shown by a generation of scholars from Walter Goffart and Ian Wood to Chris Wickham, Andreas Fischer, and Peter Heather, the period from Rome’s fall to Aachen’s ascent deserves to be studied for its own self and not merely as another of history’s dreary “periods of transition”; after all, every age is one of transition, and the transitions involved—political, cultural, intellectual, technological, and every other type—are usually themselves the chief points of interest.

more here.

The Enduring Strength of Kashmir’s Literary Life

Sharanya Deepak at Literary Hub:

Today, Kashmiri writers are of all forms. They write folklore, journalism, novels, blogs, poems, ghazals, nazms: literature can be found scribbled on trees, on social media, in notebooks kept in attics. They write across languages: in Kashmiri, Urdu and English, and within Kashmir lie distinctions, of class, caste and language.

Today, Kashmiri writers are of all forms. They write folklore, journalism, novels, blogs, poems, ghazals, nazms: literature can be found scribbled on trees, on social media, in notebooks kept in attics. They write across languages: in Kashmiri, Urdu and English, and within Kashmir lie distinctions, of class, caste and language.

Writing in Kashmir is not only a question of importance, says Kashmiri novelist, Shahnaz Bashir in an interview with Wande Magazine but “a question of duty.” Bashir’s fiction is set in the decade of the 1990s, where Kashmir saw a series of human rights crimes by the Indian armed forces, including incarceration and mass arrests of young civilian men. Claiming that it was aiming to curb militancy, the Indian military rampaged through the region, arresting and torturing Kashmiris on sight. Bashir’s first novel The Half Mother circles a woman’s life as she waits for her son, who is taken by the Indian army, to return. It reflects on the realities of many such women who are denigrated to “halves”—half wife, half mother—when their male family members are disappeared.

more here.

Thursday, October 22, 2020

What if, instead of hating each other’s beliefs, we learned more about where they come from?

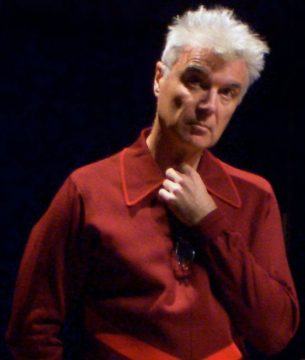

David Byrne in Reasons to be Cheerful:

Like a lot of folks, I occasionally hear people espouse values and beliefs different and often counter to my own. When I was young, I didn’t understand this. Many of these beliefs and positions seemed irrational to me. How could people believe such crazy things? But as I read, traveled and met more people, I learned that values and convictions that might seem strange to me often serve a purpose for others.

Like a lot of folks, I occasionally hear people espouse values and beliefs different and often counter to my own. When I was young, I didn’t understand this. Many of these beliefs and positions seemed irrational to me. How could people believe such crazy things? But as I read, traveled and met more people, I learned that values and convictions that might seem strange to me often serve a purpose for others.

Sometimes that purpose is simply the sharing of these values and beliefs with others who feel the same way. Shared beliefs can foster a sense of community, or provide meaning in people’s lives. It seems that we as humans have evolved to need something that provides unity and cohesion. Sometimes that might be liking the same songs or movies. Or, if that means believing in statues that cry or space aliens, well, okay, maybe no harm done.

I have come to sense that I, too, might harbor some odd beliefs — and, like others, I come up with convoluted rationalizations for them. I have a set of values that, to me, should be seen as self evident and should therefore be adopted by everyone. But if we’re going to find common ground and live together, we need to at least attempt to understand the mindsets of the people who think differently from us.

More here.

Evolutionary Psychology: Predictively Powerful or Riddled with Just-So Stories?

Laith Al-Shawaf in Areo:

A common refrain in the social sciences is that evolutionary psychological hypotheses are “just-so stories.” Amazingly, no evidence is typically adduced for the claim—the assertion is usually just made tout court. The crux of the just-so charge is that evolutionary hypotheses are convenient narratives that researchers spin after the fact to accord with existing observations. Is this true?

A common refrain in the social sciences is that evolutionary psychological hypotheses are “just-so stories.” Amazingly, no evidence is typically adduced for the claim—the assertion is usually just made tout court. The crux of the just-so charge is that evolutionary hypotheses are convenient narratives that researchers spin after the fact to accord with existing observations. Is this true?

In reality, the evidence suggests that evolutionary approaches generate large numbers of new predictions and new discoveries about the human mind. To substantiate this claim, the findings in this essay were predicted a priori by evolutionary reasoning—in other words, the predictions were made before the studies took place. They therefore cannot be post-hoc stories concocted to fit already-existing data.

More here.

Not All Identities Are Created Equal

Razib Khan in Quillette:

In 2020, much of the public discussion of social issues revolves around notions of identity. Ideas about race, reformulations of gender, and considerations of class or religious confession. But it is not often stated that these identity categories are qualitatively different, and these differences have different implications for the real world. Some reflection on the real-world consequences of identity ought to make this apparent. Why is a party based on working-class solidarity far less sinister than a party based on a racial or ethnic group? Perhaps because being working-class is not a fixed identity, and solidarity is open to all. One’s race or ethnicity is viewed as more static. Most of us can imagine struggling to pay bills and keep a roof over our heads, but few can imagine being another race. Race-thinking is anti-empathetic by its nature.

In 2020, much of the public discussion of social issues revolves around notions of identity. Ideas about race, reformulations of gender, and considerations of class or religious confession. But it is not often stated that these identity categories are qualitatively different, and these differences have different implications for the real world. Some reflection on the real-world consequences of identity ought to make this apparent. Why is a party based on working-class solidarity far less sinister than a party based on a racial or ethnic group? Perhaps because being working-class is not a fixed identity, and solidarity is open to all. One’s race or ethnicity is viewed as more static. Most of us can imagine struggling to pay bills and keep a roof over our heads, but few can imagine being another race. Race-thinking is anti-empathetic by its nature.

Obviously, most humans have a variety of identities that they balance, synthesize, and are enriched by. Before World War I, socialists expressed their opposition to a conflict that they believed, correctly, would only bring suffering to the workers of the world. But once the Great War commenced socialist parties in the main fell into line, expressing national patriotism. This shattered the illusion of radicals that socialism would supersede nationalism, and that class solidarity trumped patriotic feeling. The rise and success of the Soviet Union as a socialist state proved that identities and emotions beyond class are necessary. A cult of personality around Stalin flourished, while to defeat Nazi Germany the Soviet Union promoted the “Great Patriotic War” rooted in a traditionalist Russian nationalism.

More here.

Sven Steinmo: OK Boomers, it’s time to grow up

Mary Somerville, for Whom the Word “Scientist” Was Coined

Maria Popova at Brain Pickings:

Despite her precocity and her early determination, it took Somerville half a lifetime to come abloom as a scientist — the spring and summer of her life passed with her genius laying restive beneath the frost of the era’s receptivity to the female mind. When Somerville was forty-six, she published her first scientific paper — a study of the magnetic properties of violet rays — which earned her praise from the inventor of the kaleidoscope, Sir David Brewster, as “the most extraordinary woman in Europe — a mathematician of the very first rank with all the gentleness of a woman.” Lord Brougham, the influential founder of the newly established Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge — with which Thoreau would take issue thirty-some years later by making a case for “the diffusion of useful ignorance,” comprising “knowledge useful in a higher sense” — was so impressed that he asked Somerville to translate a mathematical treatise by Pierre-Simon Laplace, “the Newton of France.” She took the project on, perhaps not fully aware how many years it would take to complete to her satisfaction, which would forever raise the common standard of excellence. All great works suffer from and are saved by a gladsome blindness to what they ultimately demand of their creators.

Despite her precocity and her early determination, it took Somerville half a lifetime to come abloom as a scientist — the spring and summer of her life passed with her genius laying restive beneath the frost of the era’s receptivity to the female mind. When Somerville was forty-six, she published her first scientific paper — a study of the magnetic properties of violet rays — which earned her praise from the inventor of the kaleidoscope, Sir David Brewster, as “the most extraordinary woman in Europe — a mathematician of the very first rank with all the gentleness of a woman.” Lord Brougham, the influential founder of the newly established Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge — with which Thoreau would take issue thirty-some years later by making a case for “the diffusion of useful ignorance,” comprising “knowledge useful in a higher sense” — was so impressed that he asked Somerville to translate a mathematical treatise by Pierre-Simon Laplace, “the Newton of France.” She took the project on, perhaps not fully aware how many years it would take to complete to her satisfaction, which would forever raise the common standard of excellence. All great works suffer from and are saved by a gladsome blindness to what they ultimately demand of their creators.

more here.

Mary Somerville and the Empire of Science in the Nineteenth Century

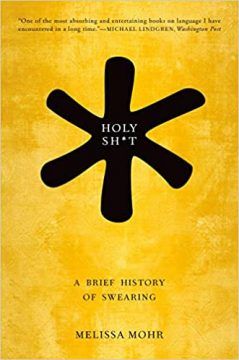

On Obscenity and Literature

Ed Simon at The Millions:

A direct line runs between the vibrant, colorful, and earthy diction of canting to cockney rhyming slang, or the endangered dialect of Polari used for decades by gay men in Great Britain, who lived under the constant threat of state punishment. All of these tongues are “obscene,” but that’s a function of their oppositional status to received language. Nothing is “dirty” about them; they are, rather, rebellions against “proper” speech, “dignified” language, “correct” talking, and they challenge that codified violence implied by the mere existence of the King’s Speech. Their differing purposes, and respective class connotations and authenticity, are illustrated by a joke wherein a hobo asks a nattily dressed businessman for some change. “’Neither a borrower nor a lender be’—that’s William Shakespeare,” says the businessman. “’Fuck you’—that’s David Mamet,” responds the panhandler. A bit of a disservice to the Bard, however, who along with Dekker and Middleton could cant with the best of them. For example, within the folio one will find “bawling, blasphemous, incharitible dog,” “paper fac’d villain,” and “embossed carbuncle,” among such other similarly colorful examples.

A direct line runs between the vibrant, colorful, and earthy diction of canting to cockney rhyming slang, or the endangered dialect of Polari used for decades by gay men in Great Britain, who lived under the constant threat of state punishment. All of these tongues are “obscene,” but that’s a function of their oppositional status to received language. Nothing is “dirty” about them; they are, rather, rebellions against “proper” speech, “dignified” language, “correct” talking, and they challenge that codified violence implied by the mere existence of the King’s Speech. Their differing purposes, and respective class connotations and authenticity, are illustrated by a joke wherein a hobo asks a nattily dressed businessman for some change. “’Neither a borrower nor a lender be’—that’s William Shakespeare,” says the businessman. “’Fuck you’—that’s David Mamet,” responds the panhandler. A bit of a disservice to the Bard, however, who along with Dekker and Middleton could cant with the best of them. For example, within the folio one will find “bawling, blasphemous, incharitible dog,” “paper fac’d villain,” and “embossed carbuncle,” among such other similarly colorful examples.

more here.

Joe Biden and the Possibility of a Remarkable Presidency

Bill McKibben in The New Yorker:

There’s really nothing in Joe Biden’s character or his record to suggest that he would be anything more than a sound, capable, regular President, which would obviously be both a great advance and a relief. If we could return to the days when we could forget that the White House even existed for days at a time, that in itself would be worth waiting in line for hours to vote. That said, there’s at least an outside chance that the stars are aligning in a way that might let Biden make remarkable change, if that is what he wants to do. America clearly has pressing problems that must be addressed, the coronavirus pandemic being the most obvious. But it also has deep structural tensions that are threatening to tear it apart, and which no President in many years has dared to address. And here’s where Biden could have an opening.

There’s really nothing in Joe Biden’s character or his record to suggest that he would be anything more than a sound, capable, regular President, which would obviously be both a great advance and a relief. If we could return to the days when we could forget that the White House even existed for days at a time, that in itself would be worth waiting in line for hours to vote. That said, there’s at least an outside chance that the stars are aligning in a way that might let Biden make remarkable change, if that is what he wants to do. America clearly has pressing problems that must be addressed, the coronavirus pandemic being the most obvious. But it also has deep structural tensions that are threatening to tear it apart, and which no President in many years has dared to address. And here’s where Biden could have an opening.

For one thing, it seems possible (not that I have let up on my phone-banking for a single evening) that he could win by a large margin—the polls currently show him further ahead than any candidate was on Election Day since Ronald Reagan, when he crushed Walter Mondale, in 1984. A nine-point win, if the margins hold through Election Day, would not be entirely a reflection on him—there’s no evidence that he unduly animates the electorate. But the body politic seems ready to reject, decisively, Donald Trump. People’s eagerness to see him gone from our public life has them voting early, amid a pandemic, in numbers that we’ve never witnessed before. That determination could presage a real groundswell that temporarily breaks the blue-red ice jam that has been frozen in place for so long; right now it also seems plausible that the Democrats could not just flip the Senate but emerge with a working majority that could get things done.

More here.

Memories Can Be Injected and Survive Amputation and Metamorphosis

Marco Altamirano in Nautilus:

The study of memory has always been one of the stranger outposts of science. In the 1950s, an unknown psychology professor at the University of Michigan named James McConnell made headlines—and eventually became something of a celebrity—with a series of experiments on freshwater flatworms called planaria. These worms fascinated McConnell not only because they had, as he wrote, a “true synaptic type of nervous system” but also because they had “enormous powers of regeneration…under the best conditions one may cut [the worm] into as many as 50 pieces” with each section regenerating “into an intact, fully-functioning organism.”

The study of memory has always been one of the stranger outposts of science. In the 1950s, an unknown psychology professor at the University of Michigan named James McConnell made headlines—and eventually became something of a celebrity—with a series of experiments on freshwater flatworms called planaria. These worms fascinated McConnell not only because they had, as he wrote, a “true synaptic type of nervous system” but also because they had “enormous powers of regeneration…under the best conditions one may cut [the worm] into as many as 50 pieces” with each section regenerating “into an intact, fully-functioning organism.”

In an early experiment, McConnell trained the worms à la Pavlov by pairing an electric shock with flashing lights. Eventually, the worms recoiled to the light alone. Then something interesting happened when he cut the worms in half. The head of one half of the worm grew a tail and, understandably, retained the memory of its training. Surprisingly, however, the tail, which grew a head and a brain, also retained the memory of its training. If a headless worm can regrow a memory, then where is the memory stored, McConnell wondered. And, if a memory can regenerate, could he transfer it?

More here.

Thursday Poem

The Moment

The moment when, after many years

of hard work and a long voyage

you stand in the center of your room,

house, half-acre, square mile, island, country,

knowing at last how you got there,

and say, I own this,

is the same moment when the trees unloose

their soft arms from around you,

the birds take back their language,

the cliffs fissure and collapse,

the air moves back from you like a wave

and you can’t breathe.

No, they whisper.

You own nothing.

You were a visitor, time after time

climbing the hill, planting the flag, proclaiming.

We never belonged to you.

You never found us.

It was always the other way round.

Wednesday, October 21, 2020

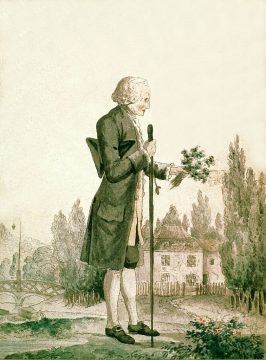

Rousseauvian Reflections on a Preferred Pronoun

Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

You will recall that while I carried on and on about myself in the first missive, I also promised that in subsequent instalments the autobiographical dimension would fall away, and the person behind the writing would for the most appear only indirectly. And yet I have in the past weeks consistently inserted myself, the author, into every topic I have touched. Why do I keep doing this? Is this not a variety of self-absorption? And if so may we perhaps distinguish between vicious and virtuous instances of what is ordinarily taken to be an unmitigated vice?

You will recall that while I carried on and on about myself in the first missive, I also promised that in subsequent instalments the autobiographical dimension would fall away, and the person behind the writing would for the most appear only indirectly. And yet I have in the past weeks consistently inserted myself, the author, into every topic I have touched. Why do I keep doing this? Is this not a variety of self-absorption? And if so may we perhaps distinguish between vicious and virtuous instances of what is ordinarily taken to be an unmitigated vice?

I believe Jean-Jacques Rousseau can assist us in answering this question. I have been reading his Confessions these past weeks (completed in 1770, published posthumously in 1782), and have found this work surprisingly helpful for understanding Rousseau as a thinker. Over the years I’ve taught The Social Contract a number of times; I read La Nouvelle Héloïse (1761) a long time ago; and more recently, inspired by Pankaj Mishra’s interpretation of the dispute between Voltaire and Rousseau concerning national sovereignty and empire in Eastern Europe, I’ve had occasion to read the latter’s Considerations on the Government of Poland (1772).

I basically share Mishra’s view that Rousseau is a crucially important counter-Enlightenment figure before this tendency found its more familiar home in Germany, and that the debate with Voltaire over the fate of Poland is therefore key to understanding what has been at stake in numerous instances, over the subsequent centuries, of conflict between the pseudo-universalism of hegemons, on the one hand, and local demands for self-determination on the other, between the imposition of external power under the guise of an objective norm and the preservation of organic folk-ways. In this conflict, I generally have more sympathy for the side defended by Rousseau, and I take Voltaire to be a disgraceful apologist for imperialism.

More here.

An Unexpected Twist Lights Up the Secrets of Turbulence

David H. Freedman in Quanta:

The blob is a cloud of turbulence in a large water tank in the lab of the University of Chicago physicist William Irvine. Unlike every other instance of turbulence that has ever been observed on Earth, Irvine’s blob isn’t a messy patch in a flowing stream of liquid, gas or plasma, or up against a wall. Rather, the blob is self-contained, a roiling, lumpy sphere that leaves the water around it mostly still. To create it and sustain it, Irvine and his graduate student Takumi Matsuzawa must repeatedly shoot “vortex loops” — essentially the water version of smoke rings — at it, eight loops at a time. “We’re building turbulence ring by ring,” said Matsuzawa.

The blob is a cloud of turbulence in a large water tank in the lab of the University of Chicago physicist William Irvine. Unlike every other instance of turbulence that has ever been observed on Earth, Irvine’s blob isn’t a messy patch in a flowing stream of liquid, gas or plasma, or up against a wall. Rather, the blob is self-contained, a roiling, lumpy sphere that leaves the water around it mostly still. To create it and sustain it, Irvine and his graduate student Takumi Matsuzawa must repeatedly shoot “vortex loops” — essentially the water version of smoke rings — at it, eight loops at a time. “We’re building turbulence ring by ring,” said Matsuzawa.

Irvine and Matsuzawa tightly control the loops that are the blob’s building blocks and study the resulting confined turbulence up close and at length. The blob could yield insights into turbulence that physicists have been chasing for two centuries — in a quest that led Richard Feynman to call turbulence the most important unsolved problem in classical physics.

More here.