Garth Greenwell in Harper’s:

The word “relevant,” I was recently surprised to discover, shares an etymology with the word “relieve.” This seems obvious enough once you know it—only a few letters separate the words—but their usages diverged so long ago that I had never associated them before. Searching out etymologies is an old habit, picked up in the decades when I aspired to be a poet. Language is fossil poetry, Emerson says, and the poem the Oxford English Dictionary lays out in this case is remarkably moving. The common forebear of both “relevant” and “relieve” is the French relever, which meant, originally, to put back into an upright position, to raise again, a word that twisted through time, scattering meanings that our two modern words have apportioned between them: to ease pain or discomfort, to make stand out, to render prominent or distinct, to rise up or rebel, to rebuild, to reinvigorate, to make higher, to set free.

The word “relevant,” I was recently surprised to discover, shares an etymology with the word “relieve.” This seems obvious enough once you know it—only a few letters separate the words—but their usages diverged so long ago that I had never associated them before. Searching out etymologies is an old habit, picked up in the decades when I aspired to be a poet. Language is fossil poetry, Emerson says, and the poem the Oxford English Dictionary lays out in this case is remarkably moving. The common forebear of both “relevant” and “relieve” is the French relever, which meant, originally, to put back into an upright position, to raise again, a word that twisted through time, scattering meanings that our two modern words have apportioned between them: to ease pain or discomfort, to make stand out, to render prominent or distinct, to rise up or rebel, to rebuild, to reinvigorate, to make higher, to set free.

I looked up this history because I realized that somehow I’d lost my sense of what we mean when we talk about “relevance,” especially the relevance of art, and I wanted to know whether the problem lay in my own understanding or in some deficiency in our usage. The word is everywhere in blurbs and reviews as a quality to admire or, more than that, as a necessary condition; “irrelevant” has joined “problematic” as a term of absolute dismissal, applied not so much to books one reads and hotly debates as to books one needn’t read at all. Artists feel the anxiety of relevance during every season of fellowship applications, those rituals of supplication, when we have to make a case for ourselves in a way that feels entirely foreign, for me at least, to the real motivations of art. Why is this the right project for this moment? these applications often ask. If I had a question like that on my mind as I tried to make art, I would never write another word. This pressure has only increased in recent years. I can still remember the shudder I felt in early 2017 when, after expressing my desire to review a newly translated European novel, an editor asked me to find “a Trump angle” to make the book relevant to his magazine’s readers. There’s something demeaning about approaching art from a predetermined angle, all the more so when that angle is determined by our current president.

More here.

The world watched today

The world watched today Could one vote — your vote — swing an entire election? Most of us abandoned this seeming fantasy not too long after we learned how elections work.

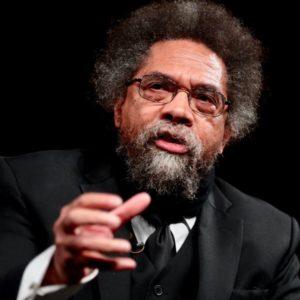

Could one vote — your vote — swing an entire election? Most of us abandoned this seeming fantasy not too long after we learned how elections work. This episode is published on November 2, 2020, the day before an historic election in the United States. An election that comes amidst growing worries about the future of democratic governance, as well as explicit claims that democracy is intrinsically unfair, inefficient, or ill-suited to the modern world. What better time to take a step back and think about the foundations of democracy? Cornel West is a well-known philosopher and public intellectual who has written extensively about race and class in America. He is also deeply interested in democracy, both in theory and in practice. We talk about what makes democracy worth fighting for, the different traditions that inform it, and the kinds of engagement it demands of its citizens.

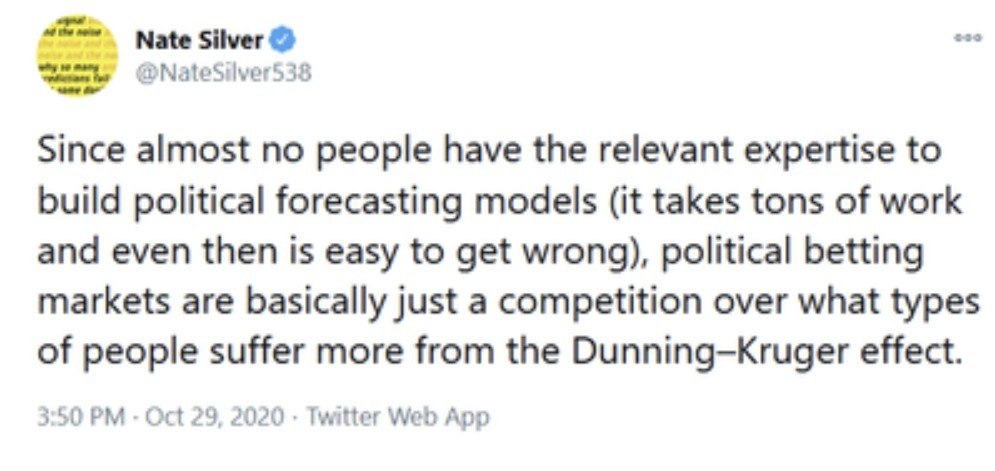

This episode is published on November 2, 2020, the day before an historic election in the United States. An election that comes amidst growing worries about the future of democratic governance, as well as explicit claims that democracy is intrinsically unfair, inefficient, or ill-suited to the modern world. What better time to take a step back and think about the foundations of democracy? Cornel West is a well-known philosopher and public intellectual who has written extensively about race and class in America. He is also deeply interested in democracy, both in theory and in practice. We talk about what makes democracy worth fighting for, the different traditions that inform it, and the kinds of engagement it demands of its citizens. But this year, the betting and prediction markets differ sharply. The betting markets see a 34 percent chance of a Trump victory, while the prediction models see but a 5 to 10 percent chance. So who should we believe?

But this year, the betting and prediction markets differ sharply. The betting markets see a 34 percent chance of a Trump victory, while the prediction models see but a 5 to 10 percent chance. So who should we believe? The unmasking of the bourgeois belief in objective reality has been so fully accomplished in America that any meaningful struggle against reality has become absurd.” Anyone reading this might think it a criticism of America. The lack of a sense of reality is a dangerous weakness in any country. Before the revolutions of 1917, Tsarist Russia was ruled by a class oblivious to existential threats within its own society. An atmosphere of unreality surrounded the rise of Nazism in Germany – a deadly threat that Britain and other countries failed to perceive until it was almost too late.

The unmasking of the bourgeois belief in objective reality has been so fully accomplished in America that any meaningful struggle against reality has become absurd.” Anyone reading this might think it a criticism of America. The lack of a sense of reality is a dangerous weakness in any country. Before the revolutions of 1917, Tsarist Russia was ruled by a class oblivious to existential threats within its own society. An atmosphere of unreality surrounded the rise of Nazism in Germany – a deadly threat that Britain and other countries failed to perceive until it was almost too late. Recently opened bookstore in southwest China looks like it came straight out of one of Dutch artist

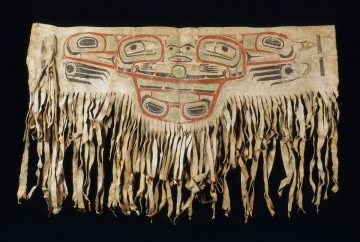

Recently opened bookstore in southwest China looks like it came straight out of one of Dutch artist  And yet, despite this vision of dreams as paradigmatically distant, many of the world’s cultures—especially outside of the modern West—have developed elaborate protocols by which dreams can be shared. The complexity of these protocols is confirmation, in one sense, of the claim that dreams are especially private, even more so than other forms of thinking. A society must work very hard indeed to make them sharable; they must be wrestled into this life from that nighttime one. But these protocols are also somehow a rebuke to the philosophers’ skepticism: people build their own universes in dreams, except, as we’ll see, they then go to great lengths to reconstruct and combine them into a shared one while awake. This seems to raise at least two questions. Why go to such great lengths to share dreams? And what happens to a culture, like our own, that doesn’t practice dream sharing, that (a few isolated realms aside, perhaps the most important being psychoanalysis) has largely given up on it?

And yet, despite this vision of dreams as paradigmatically distant, many of the world’s cultures—especially outside of the modern West—have developed elaborate protocols by which dreams can be shared. The complexity of these protocols is confirmation, in one sense, of the claim that dreams are especially private, even more so than other forms of thinking. A society must work very hard indeed to make them sharable; they must be wrestled into this life from that nighttime one. But these protocols are also somehow a rebuke to the philosophers’ skepticism: people build their own universes in dreams, except, as we’ll see, they then go to great lengths to reconstruct and combine them into a shared one while awake. This seems to raise at least two questions. Why go to such great lengths to share dreams? And what happens to a culture, like our own, that doesn’t practice dream sharing, that (a few isolated realms aside, perhaps the most important being psychoanalysis) has largely given up on it? One day in 1757 the poet Christopher Smart went out to St James’s Park, started praying loudly and couldn’t stop. He was hauled off to St Luke’s Asylum, where a cascade of ecstatic verse proceeded to pour from him, in which he identified his cat companion, Jeoffry, as ‘the servant of the Living God’. According to Smart’s delighted itemising, Jeoffry served the Almighty by catching rats, keeping his front paws pernickety clean and observing the watches of the night. He was a peaceable soul too, kissing neighbouring cats ‘in kindness’ and letting a mouse escape one time in seven. But perhaps Jeoffry’s greatest accomplishment was his ability to ‘spraggle upon waggle’. Both spraggling and waggling, Smart’s magnificat suggests, are deeply pleasing to the Lord.

One day in 1757 the poet Christopher Smart went out to St James’s Park, started praying loudly and couldn’t stop. He was hauled off to St Luke’s Asylum, where a cascade of ecstatic verse proceeded to pour from him, in which he identified his cat companion, Jeoffry, as ‘the servant of the Living God’. According to Smart’s delighted itemising, Jeoffry served the Almighty by catching rats, keeping his front paws pernickety clean and observing the watches of the night. He was a peaceable soul too, kissing neighbouring cats ‘in kindness’ and letting a mouse escape one time in seven. But perhaps Jeoffry’s greatest accomplishment was his ability to ‘spraggle upon waggle’. Both spraggling and waggling, Smart’s magnificat suggests, are deeply pleasing to the Lord. COUNTERFACTUALS TEND TO BE more intriguing when they bend sinister. They reassure us that our times aren’t as bad as they might have been, but warn us about where we could still end up. What if xenophobic Charles Lindbergh had been elected president in 1940, as in Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America, or if the Axis powers had prevailed in World War II, as in Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle? Would it be worth, however, indulging a less theatrical alternative history: what if Vice President Henry A. Wallace had been re-nominated as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s running mate in 1944 rather than being replaced by Harry Truman?

COUNTERFACTUALS TEND TO BE more intriguing when they bend sinister. They reassure us that our times aren’t as bad as they might have been, but warn us about where we could still end up. What if xenophobic Charles Lindbergh had been elected president in 1940, as in Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America, or if the Axis powers had prevailed in World War II, as in Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle? Would it be worth, however, indulging a less theatrical alternative history: what if Vice President Henry A. Wallace had been re-nominated as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s running mate in 1944 rather than being replaced by Harry Truman? Unless you’re a physicist or an engineer, there really isn’t much reason for you to know about partial differential equations. I know. After years of poring over them in undergrad while studying mechanical engineering, I’ve never used them since in the real world.

Unless you’re a physicist or an engineer, there really isn’t much reason for you to know about partial differential equations. I know. After years of poring over them in undergrad while studying mechanical engineering, I’ve never used them since in the real world. Suppose you believe the state should look after the wellbeing of the poor and combat the structural forces that enrich the wealthy. Suppose you’re in a two-party electoral system, and that the party notionally aligned with your ideals made a Faustian pact with business elites to shore up the policies that perpetuate poverty – low minimum wages, tax incentives for rent-seekers, privatisation of public services, etc. What kind of ballot should you cast? You can’t vote for the party pushing things further to the Right. And if you don’t vote, or you vote for someone who’s almost certain not to win, you’re helping that same regressive party get elected. Yet lending your support to the ‘lesser of two evils’ candidate, whose platform you don’t really support, feels like an unacceptable compromise to your ideals.

Suppose you believe the state should look after the wellbeing of the poor and combat the structural forces that enrich the wealthy. Suppose you’re in a two-party electoral system, and that the party notionally aligned with your ideals made a Faustian pact with business elites to shore up the policies that perpetuate poverty – low minimum wages, tax incentives for rent-seekers, privatisation of public services, etc. What kind of ballot should you cast? You can’t vote for the party pushing things further to the Right. And if you don’t vote, or you vote for someone who’s almost certain not to win, you’re helping that same regressive party get elected. Yet lending your support to the ‘lesser of two evils’ candidate, whose platform you don’t really support, feels like an unacceptable compromise to your ideals. The camera costs $58,990, including a 70mm lens made by Phase One partner Rodenstock. If you want the 23mm, 32mm or 50mm lenses, expect to pony up another $11,990 each. A

The camera costs $58,990, including a 70mm lens made by Phase One partner Rodenstock. If you want the 23mm, 32mm or 50mm lenses, expect to pony up another $11,990 each. A  Sean Connery

Sean Connery