Catherine Wilson in Aeon:

Catherine Wilson in Aeon:

Like many people, I am skeptical of any book, lecture or article offering to divulge the secrets of happiness. To me, happiness is episodic. It’s there at a moment of insight over drinks with a friend, when hearing a new and affecting piece of music on the radio, sharing confidences with a relative or waking up from a good night’s sleep after a bout of the flu. Happiness is a feeling of in-the-moment joy that can’t be chased and caught and which can’t last very long.

But satisfaction with how things are going is different than happiness. Satisfaction has to do with the qualities and arrangements of life that make us want to get out of bed in the morning, find out what’s happening in the world, and get on with whatever the day brings. There are obstacles to satisfaction, and they can be, if not entirely removed, at least lowered. Some writers argue that satisfaction mostly depends on my genes, where I live and the season of the year, or how other people, including the government, are treating me. Nevertheless, psychology and the sharing of first-person experience acquired over many generations, can actually help.

So can philosophy. The major schools of philosophy in antiquity – Platonism, Stoicism, Aristotelianism and, my favourite, Epicureanism, addressed the question of the good life directly. The philosophers all subscribed to an ideal of ‘life according to nature’, by which they meant both human and nonhuman nature, while disagreeing among themselves about what that entailed.

More here.

The American expat has enjoyed a storied position in culture and literature. In France, the role has been romanticized from Gene Kelly tap dancing his way through “An American in Paris” to Ernest Hemingway’s Paris-set “A Moveable Feast,” where he wrote, “There are only two places in the world where we can live happy: at home and in Paris.” Numbering around 250,000, Americans in France tend to lean Democratic and enjoy elite status, says Oleg Kobtzeff, an associate professor of international and comparative politics at the American University of Paris. “So Americans in France are themselves examples of soft power.” It’s not that they’ve been universally loved. Former President George W. Bush’s war on terror, including the Iraq War of 2003 that many allies condemned, made him as unpopular in France as President Trump is today.

The American expat has enjoyed a storied position in culture and literature. In France, the role has been romanticized from Gene Kelly tap dancing his way through “An American in Paris” to Ernest Hemingway’s Paris-set “A Moveable Feast,” where he wrote, “There are only two places in the world where we can live happy: at home and in Paris.” Numbering around 250,000, Americans in France tend to lean Democratic and enjoy elite status, says Oleg Kobtzeff, an associate professor of international and comparative politics at the American University of Paris. “So Americans in France are themselves examples of soft power.” It’s not that they’ve been universally loved. Former President George W. Bush’s war on terror, including the Iraq War of 2003 that many allies condemned, made him as unpopular in France as President Trump is today. Ben Railton in US Intellectual History Blog:

Ben Railton in US Intellectual History Blog: Samuel Clowes Huneke in Boston Review:

Samuel Clowes Huneke in Boston Review: Catherine Wilson in Aeon:

Catherine Wilson in Aeon: Robert Hockett in Forbes:

Robert Hockett in Forbes: For anyone with a platform,

For anyone with a platform,  The cable news talking heads seem obsessed with Joe Biden’s “significant” lead over Donald Trump in the national polls – as if this lead signifies a certain coming Biden victory in the presidential election. Also feeding the narrative that Biden is likely to win are stories and film clips of millions of Americans standing in long lines to vote early in record numbers.

The cable news talking heads seem obsessed with Joe Biden’s “significant” lead over Donald Trump in the national polls – as if this lead signifies a certain coming Biden victory in the presidential election. Also feeding the narrative that Biden is likely to win are stories and film clips of millions of Americans standing in long lines to vote early in record numbers. B

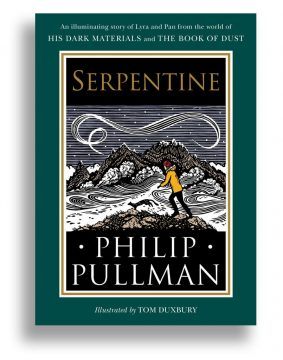

B Since the last volume of “His Dark Materials” appeared in 2000, Pullman has written two more (superb) volumes of a second trilogy called “

Since the last volume of “His Dark Materials” appeared in 2000, Pullman has written two more (superb) volumes of a second trilogy called “ ANTHONY DAVIS, winner of the

ANTHONY DAVIS, winner of the  In 2002 the Cambridge astrophysicist and Astronomer Royal Lord Rees predicted that, by the end of 2020, “bioterror or bioerror will lead to one million casualties in a single event”. In 2017 the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker took the other side in a formal bet. As the terms of the wager defined casualties to include “victims requiring hospitalization”, Rees had already won long before the global death toll of Covid-19 passed the one million mark in September. Sadly for him, the stake was a meagre $400.

In 2002 the Cambridge astrophysicist and Astronomer Royal Lord Rees predicted that, by the end of 2020, “bioterror or bioerror will lead to one million casualties in a single event”. In 2017 the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker took the other side in a formal bet. As the terms of the wager defined casualties to include “victims requiring hospitalization”, Rees had already won long before the global death toll of Covid-19 passed the one million mark in September. Sadly for him, the stake was a meagre $400. The 1990s now seem as distant as the 1950s. America is famously polarized into cultural tribes, each regarding the other with contempt and alarm. In the White House sits a populist entertainer with little evident commitment to constitutional norms. Sober scholars publish books with titles such as How Democracies Die

The 1990s now seem as distant as the 1950s. America is famously polarized into cultural tribes, each regarding the other with contempt and alarm. In the White House sits a populist entertainer with little evident commitment to constitutional norms. Sober scholars publish books with titles such as How Democracies Die  Silliness is not such a stretch as one would think, should one think of Wittgenstein. The ludic is at play, from conception, in the language-game itself; or the duck-rabbit as a vehicle of ambiguity, a perceptual “third thing,” a visual neologism: now ears … now beak, or “Both; not side-by-side, however, but about the one via the other.” Silliness is ruminative, i.e., we must look back over time for its sense to resonate. And it seeks a beyond. I consider the question of whether the two-headed calf should be counted as one animal or two—a serious moment for the Vatican Belvedere Gardens of 1625. Three, of course. “For the physicians, the feature distinguishing the individual was the brain; for followers of Aristotle, the heart,” wrote Carlo Ginzburg. And the dissection of the animal “was done with the aim of establishing not the ‘character’ peculiar to that particular animal, but ‘the common character’ … of the species as a whole.” A parallelism: Wittgenstein’s insistence that a student learn a new word by experiencing it through practice, being responsible to it and its usage, and eventually making the word meaningful for a greater understanding of her (whole) (linguistic) (yet shared, and seen) world.

Silliness is not such a stretch as one would think, should one think of Wittgenstein. The ludic is at play, from conception, in the language-game itself; or the duck-rabbit as a vehicle of ambiguity, a perceptual “third thing,” a visual neologism: now ears … now beak, or “Both; not side-by-side, however, but about the one via the other.” Silliness is ruminative, i.e., we must look back over time for its sense to resonate. And it seeks a beyond. I consider the question of whether the two-headed calf should be counted as one animal or two—a serious moment for the Vatican Belvedere Gardens of 1625. Three, of course. “For the physicians, the feature distinguishing the individual was the brain; for followers of Aristotle, the heart,” wrote Carlo Ginzburg. And the dissection of the animal “was done with the aim of establishing not the ‘character’ peculiar to that particular animal, but ‘the common character’ … of the species as a whole.” A parallelism: Wittgenstein’s insistence that a student learn a new word by experiencing it through practice, being responsible to it and its usage, and eventually making the word meaningful for a greater understanding of her (whole) (linguistic) (yet shared, and seen) world.