Malcolm Keating in Psyche:

Malcolm Keating in Psyche:

In premodern India, debates were entertainment in courtly settings, a sport for profiteers and clever men who enjoyed a quick turn of phrase or put-down. Successful debaters gained followers, fame, even wealth. Those pragmatic aims intertwined with nobler ones: religious believers and nonbelievers debated over deep religious truths. Both inside and outside religious traditions, participants sparred over controversies with significant social implications. Even the efficacy of medical cures was hard-fought in the debate arena.

During the 9th to 10th century CE, Vācaspati Miśra, an Indian philosopher who was part of a Hindu tradition called ‘Nyāya’ (or ‘reason’) argued that debate benefits society when it aims for truth. He thought, too, that debate helps us humans achieve ultimate happiness in our short, fragile and often painful human lives. But if debate has such noble aims, should we care about winning or losing? And if debate leads us to the truth, should we always debate everyone, everywhere? To understand Vācaspati’s answer, we must first understand the Nyāya philosophy of debate.

For Nyāya philosophers, we acquire ultimate happiness by ending the self’s painful cycle of rebirth, its journey from life to life, always bound to our past actions. Before we can end this cycle, we must rid ourselves of ethical vices. And this requires knowing the truth.

More here.

In the summer of 1944, a camera was smuggled out of Auschwitz. Inside it was a roll of film with four images from the gas chambers at Birkenau, taken by members of the Jewish Sonderkommando. These photos were distributed worldwide by the Polish resistance. Two of them appear to have been taken in quick succession, discreetly, from within a shadowed doorframe. The other pair, one of which is blurred, appear to have been shot at the hip from a distance. The photos show Jewish women stripping before the gas chamber, and dead bodies waiting to be incinerated. White smoke billows as other bodies burn.

In the summer of 1944, a camera was smuggled out of Auschwitz. Inside it was a roll of film with four images from the gas chambers at Birkenau, taken by members of the Jewish Sonderkommando. These photos were distributed worldwide by the Polish resistance. Two of them appear to have been taken in quick succession, discreetly, from within a shadowed doorframe. The other pair, one of which is blurred, appear to have been shot at the hip from a distance. The photos show Jewish women stripping before the gas chamber, and dead bodies waiting to be incinerated. White smoke billows as other bodies burn. Because there are many things to say about Susan Taubes’s remarkable 1969 novel “Divorcing,” and many of those things concern the grim side of both real life and life in the book, I’d like to start by saying that it’s funny. It’s not a comic novel, by any stretch, but neglecting to mention its humor would shortchange it and deform one’s initial idea of it.

Because there are many things to say about Susan Taubes’s remarkable 1969 novel “Divorcing,” and many of those things concern the grim side of both real life and life in the book, I’d like to start by saying that it’s funny. It’s not a comic novel, by any stretch, but neglecting to mention its humor would shortchange it and deform one’s initial idea of it. T

T

Back in 2013, another in a long line of tussles over scientism broke out. Leon Wieseltier, literary editor of The New Republic,

Back in 2013, another in a long line of tussles over scientism broke out. Leon Wieseltier, literary editor of The New Republic,  When I was a graduate student in international relations in the early 2000s, my teachers would frequently invoke the famous, though possibly apocryphal, response of the late Chinese foreign minister Zhou Enlai to the question of whether the French Revolution had been a success: “It’s too soon to tell.” Contemplating the same arc of history that forms the subtext of Zhou’s reply, we might see the United States today bending gingerly away from populist indignation and toward a potentially gentler interval of governance. Though the nation’s attention is rightly focused on domestic matters, above all on contending with a devasting pandemic, changes at the helm mean that it is open season for grand visioning from the heights, particularly as concerns America’s place in the world. Are we dispensable? Indispensable? Exceptional? Banal? Imperialist? Heroic? Or simply unsound?

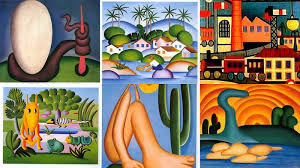

When I was a graduate student in international relations in the early 2000s, my teachers would frequently invoke the famous, though possibly apocryphal, response of the late Chinese foreign minister Zhou Enlai to the question of whether the French Revolution had been a success: “It’s too soon to tell.” Contemplating the same arc of history that forms the subtext of Zhou’s reply, we might see the United States today bending gingerly away from populist indignation and toward a potentially gentler interval of governance. Though the nation’s attention is rightly focused on domestic matters, above all on contending with a devasting pandemic, changes at the helm mean that it is open season for grand visioning from the heights, particularly as concerns America’s place in the world. Are we dispensable? Indispensable? Exceptional? Banal? Imperialist? Heroic? Or simply unsound? The Confederate immigrants didn’t impose their way of life in São Paulo’s rural interior. On neighboring plantations, enslaved women were raising the white artists who would become the country’s major modernists. Brazil’s most famous modernist painter, Tarsila do Amaral, muse of Antropofagia, grew up on her family’s coffee plantation, a half hour’s drive from the American colony. Antropofagia was a movement of “cultural cannibalism” based on a caricature of the Tupi indigenous people as cannibals; elite white Brazilians would “cannibalize” French styles in the production of Brazilian subject matter: Black people. A year before her death, do Amaral explained that the subject for her first anthropophagic painting, A Negra (1923), was a “female slave” she remembered from her youth, and described in vivid detail I won’t repeat how the woman had stretched her breasts so that she might breastfeed while working. Chattel slavery legally ended in Brazil on May 13, 1888, when do Amaral was one year old, so her explanation was technically anachronistic. Either emancipation passed without notice, or her family’s plantation hummed along under a new economic arrangement so closely resembling slavery that she still referred to wage workers as “slaves.”

The Confederate immigrants didn’t impose their way of life in São Paulo’s rural interior. On neighboring plantations, enslaved women were raising the white artists who would become the country’s major modernists. Brazil’s most famous modernist painter, Tarsila do Amaral, muse of Antropofagia, grew up on her family’s coffee plantation, a half hour’s drive from the American colony. Antropofagia was a movement of “cultural cannibalism” based on a caricature of the Tupi indigenous people as cannibals; elite white Brazilians would “cannibalize” French styles in the production of Brazilian subject matter: Black people. A year before her death, do Amaral explained that the subject for her first anthropophagic painting, A Negra (1923), was a “female slave” she remembered from her youth, and described in vivid detail I won’t repeat how the woman had stretched her breasts so that she might breastfeed while working. Chattel slavery legally ended in Brazil on May 13, 1888, when do Amaral was one year old, so her explanation was technically anachronistic. Either emancipation passed without notice, or her family’s plantation hummed along under a new economic arrangement so closely resembling slavery that she still referred to wage workers as “slaves.” Samuel Johnson famously remarked, ‘It is commonly observed, that when two Englishmen meet, their first talk is of the weather; they are in haste to tell each other, what each must already know.’ Virginia Woolf politely added that Englishwomen also talk about the weather but thought there should be strict rules attached to all such discussions. A hostess or a novelist might talk about the weather to settle a guest or a reader, but they should move swiftly on to more interesting themes. A novel that considers nothing but the weather was most probably written by Arnold Bennett (I paraphrase). Mark Twain took this further, promising in the opening of The American Claimant that ‘no weather will be found in this book’ as ‘it is plain that persistent intrusions of weather are bad for both reader and author’.

Samuel Johnson famously remarked, ‘It is commonly observed, that when two Englishmen meet, their first talk is of the weather; they are in haste to tell each other, what each must already know.’ Virginia Woolf politely added that Englishwomen also talk about the weather but thought there should be strict rules attached to all such discussions. A hostess or a novelist might talk about the weather to settle a guest or a reader, but they should move swiftly on to more interesting themes. A novel that considers nothing but the weather was most probably written by Arnold Bennett (I paraphrase). Mark Twain took this further, promising in the opening of The American Claimant that ‘no weather will be found in this book’ as ‘it is plain that persistent intrusions of weather are bad for both reader and author’. Given that

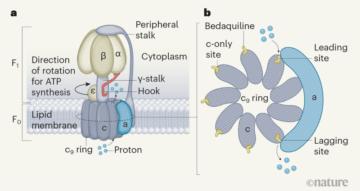

Given that  The 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for the development of an imaging method called cryo-electron microscopy. On bestowing the prize, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences stated that this technique has “moved biochemistry into a new era”.

The 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for the development of an imaging method called cryo-electron microscopy. On bestowing the prize, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences stated that this technique has “moved biochemistry into a new era”.

“Surely, after 62 years, we should have an exact formulation of some serious part of quantum mechanics?” wrote the eminent Northern Irish physicist John Bell in the opening salvo of his Physics World article, “

“Surely, after 62 years, we should have an exact formulation of some serious part of quantum mechanics?” wrote the eminent Northern Irish physicist John Bell in the opening salvo of his Physics World article, “