Richard Dawkins in The Spectator:

For, whether we like it or not, it is a true fact that we are cousins of kangaroos, that we share an ancestor with starfish, and that we and the starfish and kangaroo share a more remote ancestor with jellyfish. The DNA code is a digital code, differing from computer codes only in being quaternary instead of binary. We know the precise details of the intermediate stages by which the code is read in our cells, and its four-letter alphabet translated, by molecular assembly-line machines called ribosomes, into a 20-letter alphabet of amino acids, the building blocks of protein chains and so of bodies.

For, whether we like it or not, it is a true fact that we are cousins of kangaroos, that we share an ancestor with starfish, and that we and the starfish and kangaroo share a more remote ancestor with jellyfish. The DNA code is a digital code, differing from computer codes only in being quaternary instead of binary. We know the precise details of the intermediate stages by which the code is read in our cells, and its four-letter alphabet translated, by molecular assembly-line machines called ribosomes, into a 20-letter alphabet of amino acids, the building blocks of protein chains and so of bodies.

If your philosophy dismisses all that as patriarchal domination, so much the worse for your philosophy. Perhaps you should stay away from doctors with their experimentally tested medicines, and go to a shaman or witch doctor instead. If you need to travel to a conference of like-minded philosophers, you’d better not go by air. Planes fly because a lot of scientifically trained mathematicians and engineers got their sums right. They did not use ‘intuitive ways of knowing’. Whether they happened to be white and male or sky-blue-pink and hermaphrodite is supremely, triumphantly irrelevant. Logic is logic is logic, no matter if the individual who wields it also happens to wield a penis. A mathematical proof reveals a definite truth, no matter whether the mathematician ‘identifies as’ female, male or hippopotamus. If you decide to fly to that conference, Newton’s laws and Bernoulli’s principle will see you safe. And no, Newton’s Principia is not a ‘rape manual’, as was ludicrously said by the noted feminist philosopher Sandra Harding. It is a supreme work of genius by one of Homo sapiens’s most sapient specimens — who also happened to be a not very nice man.

More here.

As the US confronts both a political crisis of presidential succession and a worsening pandemic, it might be instructive, though perhaps not comforting, to learn that we’ve been here before.

As the US confronts both a political crisis of presidential succession and a worsening pandemic, it might be instructive, though perhaps not comforting, to learn that we’ve been here before. We are necessarily occupied here each week with strategies for getting ourselves out of the climate crisis—it is the world’s true Klaxon-sounding emergency. But it is worth occasionally remembering that global warming is just one measure of the human domination of our planet. We got another reminder of that unwise hegemony this week, from a study so remarkable that we should just pause and absorb it.

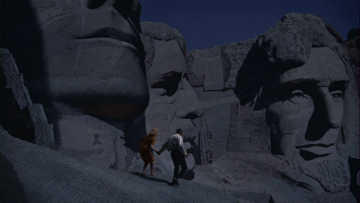

We are necessarily occupied here each week with strategies for getting ourselves out of the climate crisis—it is the world’s true Klaxon-sounding emergency. But it is worth occasionally remembering that global warming is just one measure of the human domination of our planet. We got another reminder of that unwise hegemony this week, from a study so remarkable that we should just pause and absorb it. This idea of Faulkner as fixated on the past has a long pedigree, perhaps beginning with “On The Sound and the Fury: Time in the Work of Faulkner,” a much-read 1939 essay by Jean-Paul Sartre. “In Faulkner’s work,” Sartre contends, “there is never any progression, never anything which comes from the future.” But what he describes in his quotations from the novel are Quentin Compson’s ruminations about time, not Faulkner’s. Sartre says that “Faulkner’s vision of the world can be compared to that of a man sitting in an open car and looking backwards.” But Sartre does not consider that in order for that vision to travel backwards the car has to move forward, and in that progress is change, which Warren Beck characterized as “man in motion” in his classic 1961 study, so titled, of the Snopes trilogy. Sartre—not the first philosopher to pursue an idea that overwhelms and distorts reality—argues that the past “takes on a sort of super-reality, its contours are hard and clear, unchangeable.” Tell that to any close reader of the 1936 novel Absalom, Absalom!, in which the past changes virtually moment by moment depending on who is talking.

This idea of Faulkner as fixated on the past has a long pedigree, perhaps beginning with “On The Sound and the Fury: Time in the Work of Faulkner,” a much-read 1939 essay by Jean-Paul Sartre. “In Faulkner’s work,” Sartre contends, “there is never any progression, never anything which comes from the future.” But what he describes in his quotations from the novel are Quentin Compson’s ruminations about time, not Faulkner’s. Sartre says that “Faulkner’s vision of the world can be compared to that of a man sitting in an open car and looking backwards.” But Sartre does not consider that in order for that vision to travel backwards the car has to move forward, and in that progress is change, which Warren Beck characterized as “man in motion” in his classic 1961 study, so titled, of the Snopes trilogy. Sartre—not the first philosopher to pursue an idea that overwhelms and distorts reality—argues that the past “takes on a sort of super-reality, its contours are hard and clear, unchangeable.” Tell that to any close reader of the 1936 novel Absalom, Absalom!, in which the past changes virtually moment by moment depending on who is talking. In 1938, Yasunari Kawabata, a young journalist in Tokyo, covered the battle between master Honinbo Shusai and apprentice Minoru Kitani for ultimate authority in the board game Go. It was one of the lengthiest matches in the history of competitive gaming—six months. In his 1968 Nobel Prize-winning novel inspired by these events, The Master of Go, Kawabata wrote of the decisive moment when, “Black has greater thickness and Black territory was secure, and the time was at hand for Otake’s [Kitani’s pseudonym in the book] own characteristic turn to offensive, for gnawing into enemy formations at which he was so adept.” A strategy that led Otake to victory.

In 1938, Yasunari Kawabata, a young journalist in Tokyo, covered the battle between master Honinbo Shusai and apprentice Minoru Kitani for ultimate authority in the board game Go. It was one of the lengthiest matches in the history of competitive gaming—six months. In his 1968 Nobel Prize-winning novel inspired by these events, The Master of Go, Kawabata wrote of the decisive moment when, “Black has greater thickness and Black territory was secure, and the time was at hand for Otake’s [Kitani’s pseudonym in the book] own characteristic turn to offensive, for gnawing into enemy formations at which he was so adept.” A strategy that led Otake to victory. The term “soft matter” was coined in 1970, and has become common currency in science only in the past two or three decades. Yet the substances to which it refers – such as honey, glue, flesh, soap, leather, starch, bitumen, milk, pastes and gels – have been familiar components of our material world since antiquity. The phrase, incidentally, was coined by French scientist Madeleine Veyssié, a collaborator of physics Nobel laureate Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, one of the foremost pioneers of the field. The French term, matière molle, is something of a double entendre, which would doubtless have appealed to the suave and charismatic de Gennes, well known for his almost stereotypically Gallic romantic liaisons.

The term “soft matter” was coined in 1970, and has become common currency in science only in the past two or three decades. Yet the substances to which it refers – such as honey, glue, flesh, soap, leather, starch, bitumen, milk, pastes and gels – have been familiar components of our material world since antiquity. The phrase, incidentally, was coined by French scientist Madeleine Veyssié, a collaborator of physics Nobel laureate Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, one of the foremost pioneers of the field. The French term, matière molle, is something of a double entendre, which would doubtless have appealed to the suave and charismatic de Gennes, well known for his almost stereotypically Gallic romantic liaisons. Should Cambridge University academics and students

Should Cambridge University academics and students  It is our sad lot that we love perishable things: our friends, our parents, our mentors, our partners, our pets. Those of us who incline to nature draw this consolation: most lovely natural things – the forests, the lakes, the oceans, the reefs – endure at scales remote from individual human ones. One meaning of the Anthropocene is that we must witness the unravelling of these things too. A tree we loved in childhood is gone; a favourite woodlot is felled; a local nature preserve invaded, eroded and its diversity diminished; this planet is haemorrhaging species.

It is our sad lot that we love perishable things: our friends, our parents, our mentors, our partners, our pets. Those of us who incline to nature draw this consolation: most lovely natural things – the forests, the lakes, the oceans, the reefs – endure at scales remote from individual human ones. One meaning of the Anthropocene is that we must witness the unravelling of these things too. A tree we loved in childhood is gone; a favourite woodlot is felled; a local nature preserve invaded, eroded and its diversity diminished; this planet is haemorrhaging species. A couple of days before he was scheduled to discuss, on the platform of the Tata Literary Festival 2020, his recent book Internationalism or Extinction, a group of India’s social and political activists wrote an open letter to Noam Chomsky in which they suggested that he boycott the festival. They cited the less-than-wholesome credentials of the festival’s sponsors, the Tatas, in the matter of human rights and apropos of how they ran their businesses. The activists reminded Chomsky that the Tatas’ business empire had expanded over the years by ruthlessly displacing – with active help from the Indian state, and often with brute force – vast tribal communities from their traditional habitats in several Indian provinces. They also talked about open-cast mining and other deleterious business practices the Tatas continued to pursue in flagrant disregard of environmental concerns. By lending his formidable name and his enormous prestige to the festival, the activists believed, Chomsky would only help “erase their (the Tatas’) crimes from public consciousness”.

A couple of days before he was scheduled to discuss, on the platform of the Tata Literary Festival 2020, his recent book Internationalism or Extinction, a group of India’s social and political activists wrote an open letter to Noam Chomsky in which they suggested that he boycott the festival. They cited the less-than-wholesome credentials of the festival’s sponsors, the Tatas, in the matter of human rights and apropos of how they ran their businesses. The activists reminded Chomsky that the Tatas’ business empire had expanded over the years by ruthlessly displacing – with active help from the Indian state, and often with brute force – vast tribal communities from their traditional habitats in several Indian provinces. They also talked about open-cast mining and other deleterious business practices the Tatas continued to pursue in flagrant disregard of environmental concerns. By lending his formidable name and his enormous prestige to the festival, the activists believed, Chomsky would only help “erase their (the Tatas’) crimes from public consciousness”. In the early 1980s, the painter, sculptor, and all-around technological savant

In the early 1980s, the painter, sculptor, and all-around technological savant  In the winter of 1984, Timothy Tangherlini worked on a dairy farm on the Danish island of Funen. One day, while brushing cattle in the barn, he spotted a tiny man in a hat sitting on the back of one of the cows. When Tangherlini tried to speak to the stranger, the little man jumped out the barn window. Assuming it was a trick, he told the couple that owned the farm about the encounter. They both shrugged. “That was the nisse,” they explained.

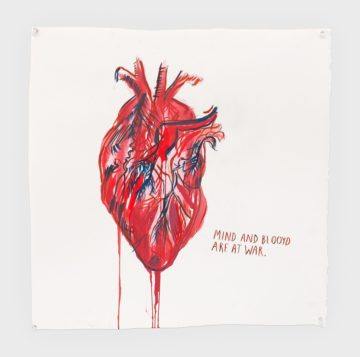

In the winter of 1984, Timothy Tangherlini worked on a dairy farm on the Danish island of Funen. One day, while brushing cattle in the barn, he spotted a tiny man in a hat sitting on the back of one of the cows. When Tangherlini tried to speak to the stranger, the little man jumped out the barn window. Assuming it was a trick, he told the couple that owned the farm about the encounter. They both shrugged. “That was the nisse,” they explained. I REMEMBER BETTER THAN MOST where I was when I knew Donald Trump would win. Not just that he would win but that “the office” would not subdue him, that he was coming because he was the crest of a wave, a force made unstoppable by its mostly unseen mass. It was October 9, 2016, I was forty-four, and I was having a heart attack. On the TV above my hospital bed, at his second debate with Hillary Clinton, Trump loomed over Clinton’s shoulder. My nurse, a Trump supporter, gave me a drip of nitroglycerin. It was a slow-moving heart attack. It’d gathered strength across days, at first fooling the ER doctors, who’d told me tests made them “95 percent certain” my heart was fine, which happens to be about the same certainty with which most pundits spoke of the imminent Clinton victory. The ER doctors had sent me home, they’d told me I could bet on those odds. But a heart is not a nation. Mine was just unlucky. Or maybe lucky, because a friend who understood the odds, or pain, better than I did insisted I return to the hospital.

I REMEMBER BETTER THAN MOST where I was when I knew Donald Trump would win. Not just that he would win but that “the office” would not subdue him, that he was coming because he was the crest of a wave, a force made unstoppable by its mostly unseen mass. It was October 9, 2016, I was forty-four, and I was having a heart attack. On the TV above my hospital bed, at his second debate with Hillary Clinton, Trump loomed over Clinton’s shoulder. My nurse, a Trump supporter, gave me a drip of nitroglycerin. It was a slow-moving heart attack. It’d gathered strength across days, at first fooling the ER doctors, who’d told me tests made them “95 percent certain” my heart was fine, which happens to be about the same certainty with which most pundits spoke of the imminent Clinton victory. The ER doctors had sent me home, they’d told me I could bet on those odds. But a heart is not a nation. Mine was just unlucky. Or maybe lucky, because a friend who understood the odds, or pain, better than I did insisted I return to the hospital. Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women worldwide, but many immunotherapies have had limited success in treating aggressive forms of the disease. “A deeper understanding of the immunobiology of breast

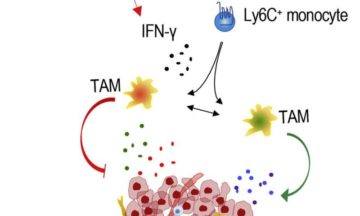

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women worldwide, but many immunotherapies have had limited success in treating aggressive forms of the disease. “A deeper understanding of the immunobiology of breast  The title of this talk

The title of this talk