Lindsay Beyerstein in Vice:

Lindsay Beyerstein in Vice:

There’s a converted three-story hotel on the industrial south side of Billings, Montana. It’s next to a large funeral home and down the street from the Montana Women’s Prison. From the outside, it looks like a nursing home, painted pink and beige, with a semi-circular driveway, and blue sign bearing the vague name “Passages.” The vibe is therapeutic but definitely not optional. It’s a place without barbed wire or armed guards, but not a place you can just leave.

The building is home to Passages, one of eight privately-owned pre-release facilities in Montana and one of only two exclusively for women. Like all pre-release centers, Passages is owned by a non-profit corporation that operates under contract to the Montana Department of Corrections (DOC). Pre-release centers are a fixture of Montana’s correctional system, and they are also used in other states including Massachusetts, Maryland, and South Carolina, as well as throughout the federal prison system.

When I approach the reception desk, I am asked to surrender my ID, “in case there’s a fire in the building.” The bright hall carpet and the breakfast bar on the ground floor are reminders of the building’s past as a Howard Johnson’s. A sign warns that escape is punishable by up to 10 years in prison.

More here.

Jesse McCarthy and Jon Baskin in The Point:

Jesse McCarthy and Jon Baskin in The Point: Peter Gordon in The Nation:

Peter Gordon in The Nation: Charisse Burden-Stelly in Boston Review:

Charisse Burden-Stelly in Boston Review: The New Left Review has introduced a blog, Sidecar. Wolfgang Streeck in Sidecar:

The New Left Review has introduced a blog, Sidecar. Wolfgang Streeck in Sidecar: Stefan Collini in The Guardian:

Stefan Collini in The Guardian: Most people approaching their 90th birthday would be forgiven for deciding that, whatever their work, enough was enough and it was time to relax. Most people, however, are not

Most people approaching their 90th birthday would be forgiven for deciding that, whatever their work, enough was enough and it was time to relax. Most people, however, are not  Ten years ago, a hawker in Tunisia set himself on fire, which

Ten years ago, a hawker in Tunisia set himself on fire, which  I was in Australia on the tail-end of my eastern book tour, the Last Book Tour perhaps, one that had taken me to Indonesia and Bangladesh earlier, when the plague, after circling for months, dove in for the kill. I left perhaps a week before Australia locked down and have wondered what would have happened if I got stuck Down Under, a world unfamiliar in ways I did not expect. During the tour, however, I spent time on the periphery of stages and outside hotel lobbies, smoking, chatting with local literary rock stars, the likes of Tara June Winch and Christos Tskiolkas. On the plane back home to Karachi, I began Christos’s

I was in Australia on the tail-end of my eastern book tour, the Last Book Tour perhaps, one that had taken me to Indonesia and Bangladesh earlier, when the plague, after circling for months, dove in for the kill. I left perhaps a week before Australia locked down and have wondered what would have happened if I got stuck Down Under, a world unfamiliar in ways I did not expect. During the tour, however, I spent time on the periphery of stages and outside hotel lobbies, smoking, chatting with local literary rock stars, the likes of Tara June Winch and Christos Tskiolkas. On the plane back home to Karachi, I began Christos’s  Almost 60 years ago, in February 1961, two teams of scientists stumbled on a discovery at the same time. Sydney Brenner in Cambridge and Jim Watson at Harvard independently spotted that genes send short-lived RNA copies of themselves to little machines called ribosomes where they are translated into proteins. ‘Sydney got most of the credit, but I don’t mind,’ Watson sighed last week when I asked him about it. They had solved a puzzle that had held up genetics for almost a decade. The short-lived copies came to be called messenger RNAs — mRNAs – and suddenly they now promise a spectacular revolution in medicine.

Almost 60 years ago, in February 1961, two teams of scientists stumbled on a discovery at the same time. Sydney Brenner in Cambridge and Jim Watson at Harvard independently spotted that genes send short-lived RNA copies of themselves to little machines called ribosomes where they are translated into proteins. ‘Sydney got most of the credit, but I don’t mind,’ Watson sighed last week when I asked him about it. They had solved a puzzle that had held up genetics for almost a decade. The short-lived copies came to be called messenger RNAs — mRNAs – and suddenly they now promise a spectacular revolution in medicine. I’ve recently spent a good chunk of time engrossed in reading A Promised Land, the first volume of President Barack Obama’s memoirs. After four years of the most impulsive and unstable president of my lifetime, hearing Obama’s calm and judicious voice in my head was like having a long, comforting talk with an old friend. His retelling of the challenges of his first two and a half years, from the global financial crisis and the passage of Obamacare to the Democrats’ midterm collapse in 2010 and the successful operation to kill Osama bin Laden in May 2011, is full of revealing details and discerning insight.

I’ve recently spent a good chunk of time engrossed in reading A Promised Land, the first volume of President Barack Obama’s memoirs. After four years of the most impulsive and unstable president of my lifetime, hearing Obama’s calm and judicious voice in my head was like having a long, comforting talk with an old friend. His retelling of the challenges of his first two and a half years, from the global financial crisis and the passage of Obamacare to the Democrats’ midterm collapse in 2010 and the successful operation to kill Osama bin Laden in May 2011, is full of revealing details and discerning insight. A poem from Paula Meehan’s second collection, Pillow Talk (1994), is called “Autobiography”. Well, in some ways a Selected Poems is like an autobiography; it expresses a sense that the life lived to date, and the work done, have some weight and perhaps some unity. Also, all autobiographies are provisional, and a Selected does not have the terminal stamp of a Collected Poems. There may yet be – one hopes there will be – many surprises in store. But there are differences: the poems included in Paula Meehan’s Selected Poems do not tell the writer’s chronological story. Rather, many of them are revisitings of phases or moments in the poet’s life, from the varying perspectives of later days. They explore those enlightening moments, when new meanings emerge from well-remembered encounters, that may only come when there is a degree of distance, for example when the adult can see what the adults in her own earlier life were about, and divine the depths of their emotions.

A poem from Paula Meehan’s second collection, Pillow Talk (1994), is called “Autobiography”. Well, in some ways a Selected Poems is like an autobiography; it expresses a sense that the life lived to date, and the work done, have some weight and perhaps some unity. Also, all autobiographies are provisional, and a Selected does not have the terminal stamp of a Collected Poems. There may yet be – one hopes there will be – many surprises in store. But there are differences: the poems included in Paula Meehan’s Selected Poems do not tell the writer’s chronological story. Rather, many of them are revisitings of phases or moments in the poet’s life, from the varying perspectives of later days. They explore those enlightening moments, when new meanings emerge from well-remembered encounters, that may only come when there is a degree of distance, for example when the adult can see what the adults in her own earlier life were about, and divine the depths of their emotions. At other times and in other places, traditional ways of life, social classification, and metaphysical order gave shape and coherence to the course of life, providing a picture of aging well. Each period of life had its activities, duties, and forms of flourishing.

At other times and in other places, traditional ways of life, social classification, and metaphysical order gave shape and coherence to the course of life, providing a picture of aging well. Each period of life had its activities, duties, and forms of flourishing. Once, in another life, I was a tech founder. It was the late nineties, when the Web was young, and everyone was trying to cash in on the dot-com boom. In college, two of my dorm mates and I discovered that we’d each started an Internet company in high school, and we merged them to form a single, teen-age megacorp. For around six hundred dollars a month, we rented office space in the basement of a building in town. We made Web sites and software for an early dating service, an insurance-claims-processing firm, and an online store where customers could “bargain” with a cartoon avatar for overstock goods. I lived large, spending the money I made on tuition, food, and a stereo.

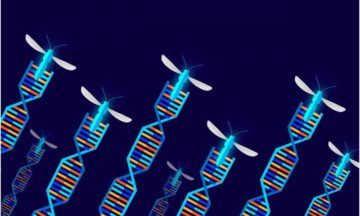

Once, in another life, I was a tech founder. It was the late nineties, when the Web was young, and everyone was trying to cash in on the dot-com boom. In college, two of my dorm mates and I discovered that we’d each started an Internet company in high school, and we merged them to form a single, teen-age megacorp. For around six hundred dollars a month, we rented office space in the basement of a building in town. We made Web sites and software for an early dating service, an insurance-claims-processing firm, and an online store where customers could “bargain” with a cartoon avatar for overstock goods. I lived large, spending the money I made on tuition, food, and a stereo. Gene drive organisms (GDOs), developed with select traits that are genetically engineered to spread through a population, have the power to dramatically alter the way society develops solutions to a range of daunting health and environmental challenges, from controlling dengue fever and malaria to protecting crops against plant pests.

Gene drive organisms (GDOs), developed with select traits that are genetically engineered to spread through a population, have the power to dramatically alter the way society develops solutions to a range of daunting health and environmental challenges, from controlling dengue fever and malaria to protecting crops against plant pests. This year marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of publication of

This year marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of publication of