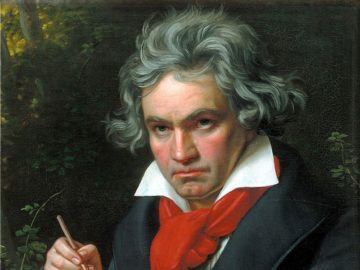

David P. Goldman in Tablet:

On Christmas Day 1989 after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Leonard Bernstein conducted Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, with its setting of Friedrich Schiller’s Ode to Joy:

On Christmas Day 1989 after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Leonard Bernstein conducted Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, with its setting of Friedrich Schiller’s Ode to Joy:

Joy, immortal incandescence!

Daughter of Elysium!

Drunk with fire from thy presence

To thy temple ground we come …

“Freude”—Joy—is the subject of Schiller’s ode, but Bernstein substituted the word “Freiheit”—Freedom—in his festive rendering of the work. That fit the occasion, but it also paid tribute to Beethoven himself, lauded as the composer of freedom by writers too numerous to mention.

There are rare moments when the triumph of the human spirit lifts us into a higher state of being. We look at perfect strangers and see the better angels of our nature, and shed the pettiness and petulance of daily life. We feel the touch of the infinite and feel the fullness of our freedom, because man is only free as a moral agent. And in such moments we hearken to the composer of freedom, whose 250th birthday falls this Dec. 16. People of good will everywhere will celebrate this anniversary with gratitude. I owe a personal debt to Beethoven, the guide and comfort of my youth, and in his honor I offer a thought about his music: It isn’t only that Beethoven was an apostle, or an exemplar of freedom, but that his music actually summons us to freedom.

More here.

For those, like me, living far from home, there is a worry so common it is banal: the Call. The call that comes when a loved one is hurt or dying. We brace ourselves against it, convinced that anticipation is inoculation against grief. To this day, I sleep with my phone on silent only when I am back in Pakistan; home is the place where late-night calls don’t seize the ground beneath you.

For those, like me, living far from home, there is a worry so common it is banal: the Call. The call that comes when a loved one is hurt or dying. We brace ourselves against it, convinced that anticipation is inoculation against grief. To this day, I sleep with my phone on silent only when I am back in Pakistan; home is the place where late-night calls don’t seize the ground beneath you. When asked to describe the circumstances of her birth, the

When asked to describe the circumstances of her birth, the  The summer solstice scene is loose and dewy, flower-crowned crowds in debauch around the bonfires. People leaped over flames and the tongues of flame licked up high into the night. In winter: private fires. Home hearths. These fires “have such power over our memory that the ancient lives slumbering beyond our oldest recollections awaken with us …revealing the deepest regions of our secret souls,” writes Henri Bosco in Malicroix. The Yule log didn’t start as a cocoa confection with meringue mushrooms on the top. It was oak burned on the night of the solstice. Depending where one lived, the ashes of the solstice fire were then spread on fields over the following days to up the yield of next season’s crop, or fed to cattle to up fatness and fertility of the herd, or placed under beds to protect against thunder, or sometimes worn in a vial around the neck. The ancient cults cast shadows in our minds, shift and flicker, their fears are still our fears, down in the darkest places of ourselves.

The summer solstice scene is loose and dewy, flower-crowned crowds in debauch around the bonfires. People leaped over flames and the tongues of flame licked up high into the night. In winter: private fires. Home hearths. These fires “have such power over our memory that the ancient lives slumbering beyond our oldest recollections awaken with us …revealing the deepest regions of our secret souls,” writes Henri Bosco in Malicroix. The Yule log didn’t start as a cocoa confection with meringue mushrooms on the top. It was oak burned on the night of the solstice. Depending where one lived, the ashes of the solstice fire were then spread on fields over the following days to up the yield of next season’s crop, or fed to cattle to up fatness and fertility of the herd, or placed under beds to protect against thunder, or sometimes worn in a vial around the neck. The ancient cults cast shadows in our minds, shift and flicker, their fears are still our fears, down in the darkest places of ourselves. Amy Nitza has spent decades helping people in crisis. The director of the Institute for Disaster Mental Health at the State University of New York at New Paltz has traveled to Puerto Rico in the wake of Hurricane Maria, to Botswana during an HIV crisis and to Haiti to help traumatized children forced into domestic servitude. But the COVID-19 pandemic, Nitza says, is different. It keeps coming at people month after month as loved ones get sick or die, as jobs are lost, and as the actions taken to avoid infection—such as isolation from family—cause intense emotional pain and stress. As of December 2020, more than 1.6 million people around the globe have died from the coronavirus. Grief, fear and economic hardship have hit every nation. In the U.S. the numbers have been overwhelming: more than 300,000 people have died, and about 17 million have been infected with the virus, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Usually disasters have survivors and responders, Nitza says, but COVID is so widespread that people are both of those things at once. “We’re training everybody [on] how to take care of themselves and how to support the people around them,” she says.

Amy Nitza has spent decades helping people in crisis. The director of the Institute for Disaster Mental Health at the State University of New York at New Paltz has traveled to Puerto Rico in the wake of Hurricane Maria, to Botswana during an HIV crisis and to Haiti to help traumatized children forced into domestic servitude. But the COVID-19 pandemic, Nitza says, is different. It keeps coming at people month after month as loved ones get sick or die, as jobs are lost, and as the actions taken to avoid infection—such as isolation from family—cause intense emotional pain and stress. As of December 2020, more than 1.6 million people around the globe have died from the coronavirus. Grief, fear and economic hardship have hit every nation. In the U.S. the numbers have been overwhelming: more than 300,000 people have died, and about 17 million have been infected with the virus, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Usually disasters have survivors and responders, Nitza says, but COVID is so widespread that people are both of those things at once. “We’re training everybody [on] how to take care of themselves and how to support the people around them,” she says. I

I  In May 1963, in a Kennedy family living room on Central Park South, Lorraine Hansberry tried to defend civil rights activists’ safety. The Raisin in the Sun playwright had come along with actor Harry Belafonte, author James Baldwin, and other luminaries at the invitation of Robert F. Kennedy and Baldwin. She listened as activist Jerome Smith tried to impress upon the attorney general the level of violence protesters were facing in the South. Smith had come straight from the Freedom Rides for medical treatment on his jaw and head, having been beaten in Birmingham.

In May 1963, in a Kennedy family living room on Central Park South, Lorraine Hansberry tried to defend civil rights activists’ safety. The Raisin in the Sun playwright had come along with actor Harry Belafonte, author James Baldwin, and other luminaries at the invitation of Robert F. Kennedy and Baldwin. She listened as activist Jerome Smith tried to impress upon the attorney general the level of violence protesters were facing in the South. Smith had come straight from the Freedom Rides for medical treatment on his jaw and head, having been beaten in Birmingham. Most of the alien civilizations that ever dotted our galaxy have probably killed themselves off already.

Most of the alien civilizations that ever dotted our galaxy have probably killed themselves off already.

Countless writers, with varying degrees of success, have reimagined the life of Jesus Christ. As my colleague

Countless writers, with varying degrees of success, have reimagined the life of Jesus Christ. As my colleague  On April 10, 1805, in honor of the Christian Holy Week, a German immigrant and conductor named

On April 10, 1805, in honor of the Christian Holy Week, a German immigrant and conductor named