Stephanie Sauer in Full Stop:

Stephanie Sauer: I, like many North Americans, grew up with Rumi’s verses infusing everything from New Age philosophies to coffee mug artwork, though his actual life and theological background remained vague. The front flap description of Moon and Sun poignantly reminds us that, “Rumi has the unique honor of being recognized as America’s best loved poet today, though he was a Muslim who lived eight hundred years ago and wrote in Persian.” Why was it important to you to re-contextualize Rumi for readers today?

Zara Houshmand: As an Iranian American, I’ve lived under the shadow of conflict between my two homes for much of my life, and it seemed to me that there was a strange irony there, a potentially fertile blind spot, and a possible bridge in Rumi’s popularity in America today. If he were alive today, Rumi probably wouldn’t get a visa to enter this country, though he’s clearly under our skin regardless.

Zara Houshmand: As an Iranian American, I’ve lived under the shadow of conflict between my two homes for much of my life, and it seemed to me that there was a strange irony there, a potentially fertile blind spot, and a possible bridge in Rumi’s popularity in America today. If he were alive today, Rumi probably wouldn’t get a visa to enter this country, though he’s clearly under our skin regardless.

It’s a commonplace that every generation deserves a new translation of the classics – presumably one that reframes them in terms of contemporary taste, though it may also reflect the evolution of scholarship. The wildly popular Coleman Barks versions are described as that kind of reframing in their origin story – Robert Bly directing Barks to “release these poems from their cages.” The cages in question were the translations of an earlier generation of British orientalists, whose scholarship was groundbreaking, but whose diction seems dated and alien to Americans now.

More here.

Schiff commented: “Reading him, we discover that we are all, like his secret agents, dissemblers selling our ‘covers’ to the world. We all have something to hide,” and we all want to align ourselves with a cause or a passion.

Schiff commented: “Reading him, we discover that we are all, like his secret agents, dissemblers selling our ‘covers’ to the world. We all have something to hide,” and we all want to align ourselves with a cause or a passion. HEIC ARTEMISIA the tombstone of Artemisia Gentileschi is said to have read. Clear and simple, forgoing the usual embellishments, such as names of father, husband, and children, dates of birth and death. HEIC ARTEMISIA, or HERE LIES ARTEMISIA.

HEIC ARTEMISIA the tombstone of Artemisia Gentileschi is said to have read. Clear and simple, forgoing the usual embellishments, such as names of father, husband, and children, dates of birth and death. HEIC ARTEMISIA, or HERE LIES ARTEMISIA. History used to be so much easier. There were the Wars of the Roses, then the Reformation, the Civil War, the Enlightenment and finally the Victorians. Each one had its own century and its distinctive tag. Throw in Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, garnish with a few zealots and adventurers, some glorious triumphs and some grisly deaths. It was all part of our Island Story. You knew where you were.

History used to be so much easier. There were the Wars of the Roses, then the Reformation, the Civil War, the Enlightenment and finally the Victorians. Each one had its own century and its distinctive tag. Throw in Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, garnish with a few zealots and adventurers, some glorious triumphs and some grisly deaths. It was all part of our Island Story. You knew where you were. In February of 1824, Charles Dickens watched in anguish as his father was arrested for debt and sent to the Marshalsea prison, just south of the Thames, in London. “I really believed at the time,” Dickens told his friend and biographer, John Forster, “that they had broken my heart.” Soon, Dickens’s mother and his younger siblings joined the father at Marshalsea, while a resentful Dickens earned money at a blacking factory, labelling pots of polish for shoes and boots. Although his father would be released within months, Dickens would never fully outrun the memory of his family’s incarceration. In her 2011 biography, Claire Tomalin notes that, in adulthood, Dickens became “an obsessive visitor of prisons.” In the autobiographical essay, “Night Walks,” he describes halting in the shadows of Newgate Prison, “touching its rough stone” and lingering “by that wicked little Debtors’ Door – shutting tighter than any other door one ever saw.” While touring America as a famous author, he made sure to go and see the prisons in Boston, New York, and Baltimore, among others.

In February of 1824, Charles Dickens watched in anguish as his father was arrested for debt and sent to the Marshalsea prison, just south of the Thames, in London. “I really believed at the time,” Dickens told his friend and biographer, John Forster, “that they had broken my heart.” Soon, Dickens’s mother and his younger siblings joined the father at Marshalsea, while a resentful Dickens earned money at a blacking factory, labelling pots of polish for shoes and boots. Although his father would be released within months, Dickens would never fully outrun the memory of his family’s incarceration. In her 2011 biography, Claire Tomalin notes that, in adulthood, Dickens became “an obsessive visitor of prisons.” In the autobiographical essay, “Night Walks,” he describes halting in the shadows of Newgate Prison, “touching its rough stone” and lingering “by that wicked little Debtors’ Door – shutting tighter than any other door one ever saw.” While touring America as a famous author, he made sure to go and see the prisons in Boston, New York, and Baltimore, among others. It was always predictable that the genome of Sars-CoV-2 would mutate. After all, that’s what viruses and other micro-organisms do. The Sars-CoV-2 genome accumulates around one or two mutations every month as it circulates. In fact, its rate of change is much lower than those of other viruses that we know about. For example, seasonal influenza mutates at such a rate that a new vaccine has to be introduced each year.

It was always predictable that the genome of Sars-CoV-2 would mutate. After all, that’s what viruses and other micro-organisms do. The Sars-CoV-2 genome accumulates around one or two mutations every month as it circulates. In fact, its rate of change is much lower than those of other viruses that we know about. For example, seasonal influenza mutates at such a rate that a new vaccine has to be introduced each year. Buddhism would undergo profound changes as it was transmitted from its origins in India east into China, in the first century CE. Terminology had to be assimilated, for one thing. And when one language is translated and assimilated into another, it is inevitable that some conceptual connections will be lost and the meaning of ideas altered. Take Zen Buddhism. In his latest book, David Hinton says that we in the West are not just once-removed from the original Zen—but twice removed. This is because the Zen we know from Japan had already lost much of the original Daoist underpinnings of Chinese Zen—known as Chan—even before the religion traveled across the Pacific to America.

Buddhism would undergo profound changes as it was transmitted from its origins in India east into China, in the first century CE. Terminology had to be assimilated, for one thing. And when one language is translated and assimilated into another, it is inevitable that some conceptual connections will be lost and the meaning of ideas altered. Take Zen Buddhism. In his latest book, David Hinton says that we in the West are not just once-removed from the original Zen—but twice removed. This is because the Zen we know from Japan had already lost much of the original Daoist underpinnings of Chinese Zen—known as Chan—even before the religion traveled across the Pacific to America. SAMIRA AHMED’S young adult novel Mad, Bad & Dangerous to Know evokes the mysterious woman at the center of Lord Byron’s 1813 poem The Giaour. Leila is the favored concubine in the court of a Turkish pasha who falls in love with the Giaour (or “infidel”), a non-Muslim man she visits in a rose garden at night. As Leila plots her doomed escape, Ahmed gives Byron’s Orientalized woman a narrative, an identity, and a voice.

SAMIRA AHMED’S young adult novel Mad, Bad & Dangerous to Know evokes the mysterious woman at the center of Lord Byron’s 1813 poem The Giaour. Leila is the favored concubine in the court of a Turkish pasha who falls in love with the Giaour (or “infidel”), a non-Muslim man she visits in a rose garden at night. As Leila plots her doomed escape, Ahmed gives Byron’s Orientalized woman a narrative, an identity, and a voice. Bears do it. Bats do it. Even European hedgehogs do it. And now it turns out that early human beings may also have been at it. They hibernated, according to fossil experts.

Bears do it. Bats do it. Even European hedgehogs do it. And now it turns out that early human beings may also have been at it. They hibernated, according to fossil experts. GLENN LOURY: I was drawing the listener’s attention to the difference between the institutional interest in having a diverse profile of participants and the interests, as I understand them, of the population which may be the beneficiary of this largesse. My point was: if you want genuine equality, this is distinct from titular equality. If you want substantive equality, this is distinct from optics equality. If you want equality of respect, of honor, of standing, of dignity, of achievement, of mastery, then you may want to think carefully about implementing systems of selection that prefer a population on a racial basis. Such a system may be inconsistent over the longer term in achieving what I call genuine equality; real equality; substantive equality; equality of standing, dignity, achievement, honor, and respect.

GLENN LOURY: I was drawing the listener’s attention to the difference between the institutional interest in having a diverse profile of participants and the interests, as I understand them, of the population which may be the beneficiary of this largesse. My point was: if you want genuine equality, this is distinct from titular equality. If you want substantive equality, this is distinct from optics equality. If you want equality of respect, of honor, of standing, of dignity, of achievement, of mastery, then you may want to think carefully about implementing systems of selection that prefer a population on a racial basis. Such a system may be inconsistent over the longer term in achieving what I call genuine equality; real equality; substantive equality; equality of standing, dignity, achievement, honor, and respect. To appreciate fully how the seemingly incidental presence of a ceramic folk craft from Latin America – when polished into pertinence by Velázquez’s virtuoso brush- becomes a visionary lens through which we glimpse the world anew, we must first remind ourselves of the cultural context from which the painting emerged and what it purports to portray. On one significant level, the work provides a self-portrait of the 57-year-old artist four years before his death in 1600, after he had spent more than three decades as court painter to King Philip IV of Spain. Palette in hand on the left side of the painting, Velázquez’s life-size selfie stares our way as if we were the very subject that he is busy capturing on an enormous canvas that rises in front of him – a painting-within-a-painting whose imaginary surface we cannot see.

To appreciate fully how the seemingly incidental presence of a ceramic folk craft from Latin America – when polished into pertinence by Velázquez’s virtuoso brush- becomes a visionary lens through which we glimpse the world anew, we must first remind ourselves of the cultural context from which the painting emerged and what it purports to portray. On one significant level, the work provides a self-portrait of the 57-year-old artist four years before his death in 1600, after he had spent more than three decades as court painter to King Philip IV of Spain. Palette in hand on the left side of the painting, Velázquez’s life-size selfie stares our way as if we were the very subject that he is busy capturing on an enormous canvas that rises in front of him – a painting-within-a-painting whose imaginary surface we cannot see. Recently, I won’t say exactly when but embarrassingly late in life, I realized that books had been lying to me. Movies were slightly better, but still untruthful. To put it another way, I realized that nothing is connected. Nothing is central. Not all things happen at the same time, or a millisecond before or after that time, or at midnight, or on anniversaries.

Recently, I won’t say exactly when but embarrassingly late in life, I realized that books had been lying to me. Movies were slightly better, but still untruthful. To put it another way, I realized that nothing is connected. Nothing is central. Not all things happen at the same time, or a millisecond before or after that time, or at midnight, or on anniversaries. Specifically, I want to suggest that the advent of Impressionism around 1870 marks a fundamental break in what I will call the dialectical continuity of French painting going back to the middle of the eighteenth century, when a new conception of the absorptive and dramatic tableau came to the fore in the paintings of Jean-Baptiste Greuze (themselves inconceivable apart from the precedent of the genre paintings of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin) and the art critical and theoretical writings of the polymath philosophe Denis Diderot, the founder of art criticism as we know it. This is the fateful development analyzed in my 1980 book, Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot, in which I argue (I would like to think I demonstrate) that starting in the mid-1750s and 1760s in France the art of painting found it necessary to confront a new imperative: to find the means to suspend or neutralize—to somehow wall off—the now suddenly distracting presence of the beholder; or to put this slightly differently, to somehow establish the supreme fiction or ontological illusion that the beholder does not exist, that there is no one standing before the painting. I describe this imperative in terms of a need to stave off, if possible to overcome, a newly distinct danger of theatricality. And I argue that this was to be accomplished with the aide of two principal strategies: first, the thematization of absorption, which is to say the depiction of personages each of whom was felt to be entirely caught up (absorbed) in whatever was understood to be taking place within the representation; and second, the promotion of a new, more exigent ideal of dramatic unity, according to which all the elements in the painting were directed toward a single dramatic end, thereby achieving a compositional effect of closure vis-à-vis the beholder.

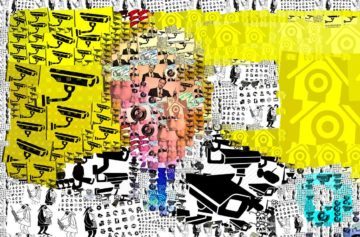

Specifically, I want to suggest that the advent of Impressionism around 1870 marks a fundamental break in what I will call the dialectical continuity of French painting going back to the middle of the eighteenth century, when a new conception of the absorptive and dramatic tableau came to the fore in the paintings of Jean-Baptiste Greuze (themselves inconceivable apart from the precedent of the genre paintings of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin) and the art critical and theoretical writings of the polymath philosophe Denis Diderot, the founder of art criticism as we know it. This is the fateful development analyzed in my 1980 book, Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot, in which I argue (I would like to think I demonstrate) that starting in the mid-1750s and 1760s in France the art of painting found it necessary to confront a new imperative: to find the means to suspend or neutralize—to somehow wall off—the now suddenly distracting presence of the beholder; or to put this slightly differently, to somehow establish the supreme fiction or ontological illusion that the beholder does not exist, that there is no one standing before the painting. I describe this imperative in terms of a need to stave off, if possible to overcome, a newly distinct danger of theatricality. And I argue that this was to be accomplished with the aide of two principal strategies: first, the thematization of absorption, which is to say the depiction of personages each of whom was felt to be entirely caught up (absorbed) in whatever was understood to be taking place within the representation; and second, the promotion of a new, more exigent ideal of dramatic unity, according to which all the elements in the painting were directed toward a single dramatic end, thereby achieving a compositional effect of closure vis-à-vis the beholder. The Trump years have transformed the Greater Evil Party, formerly known as the GOP, into a party too appalling even to contemplate without going berserk. Alarmists expected all sorts of bad things to come from the Trump presidency, but no one quite expected this. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party has sprouted a left wing too extensive and organized for that wretched party’s leaders and donors to marginalize. Even after the Occupy movements of 2011 and the Sanders campaign in 2016, this too was unexpected. It is also, by far, the best thing that has happened in American politics in decades. It probably would not have happened but for Trump. Who would have expected that? Who could have imagined that his unmitigated vileness and his incompetence would have had that unintended effect? It did, though. And so, calls for social policies comparable to those achieved in advanced social democracies a half century ago have become almost mainstream. More amazing still, thanks to Trump more than anyone else, the word “socialism” need no longer be uttered only in whispers in Democratic Party circles.

The Trump years have transformed the Greater Evil Party, formerly known as the GOP, into a party too appalling even to contemplate without going berserk. Alarmists expected all sorts of bad things to come from the Trump presidency, but no one quite expected this. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party has sprouted a left wing too extensive and organized for that wretched party’s leaders and donors to marginalize. Even after the Occupy movements of 2011 and the Sanders campaign in 2016, this too was unexpected. It is also, by far, the best thing that has happened in American politics in decades. It probably would not have happened but for Trump. Who would have expected that? Who could have imagined that his unmitigated vileness and his incompetence would have had that unintended effect? It did, though. And so, calls for social policies comparable to those achieved in advanced social democracies a half century ago have become almost mainstream. More amazing still, thanks to Trump more than anyone else, the word “socialism” need no longer be uttered only in whispers in Democratic Party circles. Mind-wandering is often considered a harmless quirk, as in the cliché of the scatter-brained professor. But it has real consequences. Let’s begin with the bad ones. Absentminded people perform less well on tests that require focused attention, such as reading comprehension tests. More worrisome, they also perform more poorly on tests that you better not flunk if you have any career aspirations. Among them is the Scholastic Aptitude Test that many colleges require for admission. But mind-wandering also has an upside—at least for well-trained minds. Indeed, many anecdotes of creators like Einstein, Newton, and eminent mathematician Henri Poincaré, report that these scientists solved important problems while not actually working on anything. The common wisdom that the best ideas arrive in the shower is exemplified by Archimedes’s discovery of how to measure an object’s volume. (OK, he was in a bathtub.) But while Archimedes’s discovery was triggered by the rising water as he entered the tub, other breakthroughs surface apropos of nothing. Take this well-known quote from the Poincaré describing a period in his life when he had worked without success on a mathematical problem:

Mind-wandering is often considered a harmless quirk, as in the cliché of the scatter-brained professor. But it has real consequences. Let’s begin with the bad ones. Absentminded people perform less well on tests that require focused attention, such as reading comprehension tests. More worrisome, they also perform more poorly on tests that you better not flunk if you have any career aspirations. Among them is the Scholastic Aptitude Test that many colleges require for admission. But mind-wandering also has an upside—at least for well-trained minds. Indeed, many anecdotes of creators like Einstein, Newton, and eminent mathematician Henri Poincaré, report that these scientists solved important problems while not actually working on anything. The common wisdom that the best ideas arrive in the shower is exemplified by Archimedes’s discovery of how to measure an object’s volume. (OK, he was in a bathtub.) But while Archimedes’s discovery was triggered by the rising water as he entered the tub, other breakthroughs surface apropos of nothing. Take this well-known quote from the Poincaré describing a period in his life when he had worked without success on a mathematical problem: