Ray Monk in Prospect:

In the 20th century an unfortunate gulf opened up in philosophy between the “continental” and “analytic” schools. Even if you’ve never studied the subject, you might well have heard of this one split. But as the British moral philosopher Bernard Williams once pointed out, the very characterisation of this gulf is odd—one school being characterised by its qualities, the other geographically, like dividing cars between four-wheel drive models and those made in Japan.

In the 20th century an unfortunate gulf opened up in philosophy between the “continental” and “analytic” schools. Even if you’ve never studied the subject, you might well have heard of this one split. But as the British moral philosopher Bernard Williams once pointed out, the very characterisation of this gulf is odd—one school being characterised by its qualities, the other geographically, like dividing cars between four-wheel drive models and those made in Japan.

Unsurprisingly, no one has come up with a satisfactory way of drawing the line between them. Broadly speaking, however, one can say that the continental school has its roots in the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl, and encompasses a range of diverse traditions, including the existentialism of Jean-Paul Sartre, the structuralism of Ferdinand de Saussure, the postmodernism of Jean-François Lyotard and the deconstructionism of Jacques Derrida. The analytic school, meanwhile, has its roots in the work of Gottlob Frege, Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein and has been until fairly recently much more narrowly focused, concentrating mainly on logic and language.

The divide is certainly strange and arguably arbitrary, but it none the less cut deep. For decades, it was possible to do a degree in philosophy at a major university in the UK or the US without once encountering any of the continental philosophers mentioned.

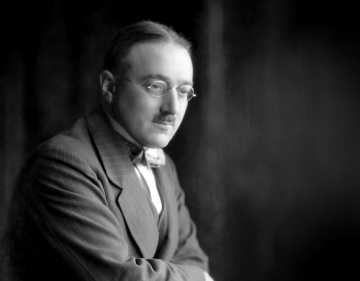

This splintering of the discipline would have appalled many philosophical greats from earlier ages. And—just possibly—the great schism would never have set in at all, had RG Collingwood, one of the most remarkable, open and eclectic minds of the 20th century, not died prematurely in 1943. But as it was, his Oxford chair was filled by Gilbert Ryle, a man in whose image British philosophy was soon remade. And a man who did more than his fair share to entrench the gulf.

More here.