Yelena Furman in The Baffler:

AS A PROFESSOR OF MINE in graduate school used to say, there is more to Russian literature than Tolstoevsky, a witticism borne out of frustration with American readers’ familiarity with just two writers at the expense of a vast and varied body of works. You can add Chekhov, Turgenev, Pushkin, and several twentieth-century names to the list of Russian writers read by English speakers. To a large degree, this paucity is not surprising: the availability of English translations depends on a combination of financial factors and publishers’ preferences, which tend toward known entities. The field of English-language translation constitutes a kind of canon of its own.

AS A PROFESSOR OF MINE in graduate school used to say, there is more to Russian literature than Tolstoevsky, a witticism borne out of frustration with American readers’ familiarity with just two writers at the expense of a vast and varied body of works. You can add Chekhov, Turgenev, Pushkin, and several twentieth-century names to the list of Russian writers read by English speakers. To a large degree, this paucity is not surprising: the availability of English translations depends on a combination of financial factors and publishers’ preferences, which tend toward known entities. The field of English-language translation constitutes a kind of canon of its own.

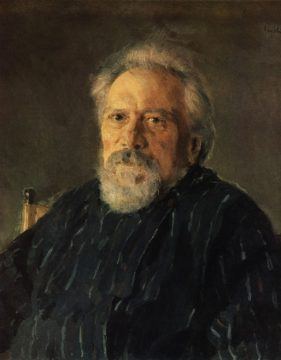

In the twenty-first century, when notions of canon formation have undergone significant expansion, the translation of Russian works in the United States has begun to reflect this shift. As the Russian Library at Columbia University Press states on its website, it publishes “works previously unavailable in English and those ripe for new translations.” Archipelago Books, Deep Vellum, and Ugly Duckling Presse have brought out translations of several notable contemporary Russian writers. Now, NYRB Classics has published Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk: Selected Stories of Nikolai Leskov (translated primarily by Donald Rayfield, along with pieces by Robert Chandler and William Edgerton), bringing together previously and newly translated works by a writer whose “absence from classic Russian literature lists must end now!” as the blurb by Gary Shteyngart exhorts. (Presumably he means in the United States, since Leskov is known in Russia, although secondarily to the nineteenth-century giants.) Rayfield recently spoke about his work on the volume for Read Russia’s Russian Literature Week.

Nikolai Leskov (1831-1895) had a tumultuous personal life and, in a related development, was a bilious human being. As Rayfield notes in his introduction, his father died when Leskov was a teenager, after which he was pawned off on relatives who did not want him. During his marriage, his wife “suffered from psychotic episodes” which Leskov “probably exacerbated,” and she lived out her days in a mental institution. Due to subsequent relationships that went awry, including one with his servant, he at a certain point “became the sole charge of four children by three different women.”

More here.

It’s tempting to presume a clear line between intention and accomplishment, but Janice P. Nimura, in her enthralling new book, “The Doctors Blackwell,” tells the story of two sisters who became feminist figures almost in spite of themselves. Elizabeth Blackwell was the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States, in 1849, and she later enlisted her younger sister Emily to join her. Together they ran the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children and founded a women’s medical college — even though, as Nimura puts it, opening a separate school for women was just about the last thing they had planned to do.

It’s tempting to presume a clear line between intention and accomplishment, but Janice P. Nimura, in her enthralling new book, “The Doctors Blackwell,” tells the story of two sisters who became feminist figures almost in spite of themselves. Elizabeth Blackwell was the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States, in 1849, and she later enlisted her younger sister Emily to join her. Together they ran the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children and founded a women’s medical college — even though, as Nimura puts it, opening a separate school for women was just about the last thing they had planned to do. I want to write about a certain kind of prose. It is the kind of prose that gets lost in itself. The kind of writing that tumbles head over heels and threatens to drown in its own wake. But not quite. The kind of prose that drowns completely is not so interesting. And the prose that never gets lost is not so interesting either. In my opinion. You’ve got to teeter around and stumble just at the edge there. In my opinion.

I want to write about a certain kind of prose. It is the kind of prose that gets lost in itself. The kind of writing that tumbles head over heels and threatens to drown in its own wake. But not quite. The kind of prose that drowns completely is not so interesting. And the prose that never gets lost is not so interesting either. In my opinion. You’ve got to teeter around and stumble just at the edge there. In my opinion. Imagine spilling a plate of food into your lap in front of a crowd. Afterwards, you might fix your gaze on your cell phone to avoid acknowledging the bumble to onlookers. Similarly, after disappointing your family or colleagues, it can be hard to look them in the eye. Why do people avoid acknowledging faux pas or transgressions that they know an audience already knows about?

Imagine spilling a plate of food into your lap in front of a crowd. Afterwards, you might fix your gaze on your cell phone to avoid acknowledging the bumble to onlookers. Similarly, after disappointing your family or colleagues, it can be hard to look them in the eye. Why do people avoid acknowledging faux pas or transgressions that they know an audience already knows about? It was February 20, 1939, two days before George Washington’s birthday. Fritz Kuhn, leader of the prominent pro-Nazi German American Bund, took the stage at Madison Square Garden. Behind him stood a towering 30-foot portrait of the first US president between giant swastikas, and around him twenty thousand rally-goers. Posters at this infamous Pro-America Rally promised a “mass-demonstration for true Americanism,” bringing National Socialist ideals to the American people. Participants waved American flags, marched to loud drum rolls, and heard pro-fascist speeches. Speakers urged the audience to embrace National Socialism, not merely to show support for Germany, but above all because it was fundamentally American.

It was February 20, 1939, two days before George Washington’s birthday. Fritz Kuhn, leader of the prominent pro-Nazi German American Bund, took the stage at Madison Square Garden. Behind him stood a towering 30-foot portrait of the first US president between giant swastikas, and around him twenty thousand rally-goers. Posters at this infamous Pro-America Rally promised a “mass-demonstration for true Americanism,” bringing National Socialist ideals to the American people. Participants waved American flags, marched to loud drum rolls, and heard pro-fascist speeches. Speakers urged the audience to embrace National Socialism, not merely to show support for Germany, but above all because it was fundamentally American. The United States of America was founded on a conspiracy theory. In the lead-up to the War of Independence, revolutionaries argued that a tax on tea or stamps is not just a tax, but the opening gambit in a sinister plot of oppression. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were convinced — based on “a long train of abuses and usurpations” — that the king of Great Britain was conspiring to establish “an absolute Tyranny” over the colonies.

The United States of America was founded on a conspiracy theory. In the lead-up to the War of Independence, revolutionaries argued that a tax on tea or stamps is not just a tax, but the opening gambit in a sinister plot of oppression. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were convinced — based on “a long train of abuses and usurpations” — that the king of Great Britain was conspiring to establish “an absolute Tyranny” over the colonies. My daughter, a Pakistani American mother of two young children, married to an African American man of Jamaican parentage, is understandably excited about our new Veep-to-be, Kamala Harris. She keeps sending me articles by “desi” women like herself in relationships with Black men, who are excited about this new chapter dawning in American history.

My daughter, a Pakistani American mother of two young children, married to an African American man of Jamaican parentage, is understandably excited about our new Veep-to-be, Kamala Harris. She keeps sending me articles by “desi” women like herself in relationships with Black men, who are excited about this new chapter dawning in American history. During the mad rush of leaving, they had to find homes for 60 animals, a menagerie of horses, snakes, turtles, and various other creatures. Only two made the cut to tag along with them: their blue budgie parakeet, Bird, who went eerily still as they crossed the Sonoran Desert, and their Doberman, Kinch, who panted in the scorching heat.

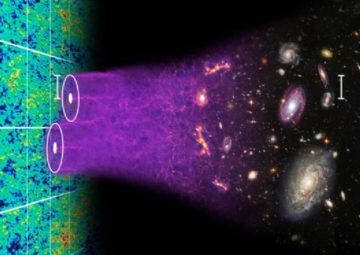

During the mad rush of leaving, they had to find homes for 60 animals, a menagerie of horses, snakes, turtles, and various other creatures. Only two made the cut to tag along with them: their blue budgie parakeet, Bird, who went eerily still as they crossed the Sonoran Desert, and their Doberman, Kinch, who panted in the scorching heat. No matter how much we might try and hide it, there’s an enormous problem staring us all in the face when it comes to the Universe. If we understood just three things:

No matter how much we might try and hide it, there’s an enormous problem staring us all in the face when it comes to the Universe. If we understood just three things: A record-breaking 4,000 Americans are now dying each day from Covid-19, while the federal government fumbles vaccine production and distribution, testing and tracing. In the midst of the worst pandemic in 100 years, more than 90 million Americans are uninsured or underinsured and can’t afford to go to a doctor when they get sick. The isolation and anxiety caused by the pandemic has resulted in a huge increase in mental illness.

A record-breaking 4,000 Americans are now dying each day from Covid-19, while the federal government fumbles vaccine production and distribution, testing and tracing. In the midst of the worst pandemic in 100 years, more than 90 million Americans are uninsured or underinsured and can’t afford to go to a doctor when they get sick. The isolation and anxiety caused by the pandemic has resulted in a huge increase in mental illness. “K

“K In all its varied symptomology, menopause put me on intimate terms with what Virginia Woolf, writing about the perspective-shifting properties of illness, called “the daily drama of the body.” Its histrionics demanded notice.

In all its varied symptomology, menopause put me on intimate terms with what Virginia Woolf, writing about the perspective-shifting properties of illness, called “the daily drama of the body.” Its histrionics demanded notice. Build a working coalition

Build a working coalition  The

The