Silvia Foti in The New York Times:

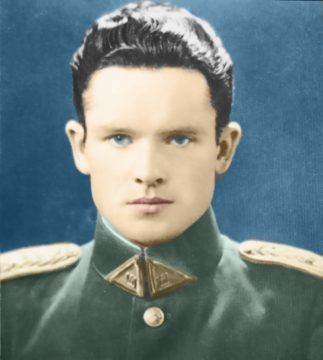

When I was growing up in Chicago during the Cold War, my parents taught me to revere my Lithuanian heritage. We sang Lithuanian songs and recited Lithuanian poems; after Lithuanian school on Saturdays, I would eat Lithuanian-style potato pancakes. My grandfather, Jonas Noreika, was a particularly important part of my family story: He was the mastermind of a 1945-1946 revolt against the Soviet Union, and was executed. A picture of him in his military uniform hung in our living room. Today, he is a hero not just in my family. He has streets, plaques and a school named after him. He was awarded the Cross of the Vytis, Lithuania’s highest posthumous honor.

When I was growing up in Chicago during the Cold War, my parents taught me to revere my Lithuanian heritage. We sang Lithuanian songs and recited Lithuanian poems; after Lithuanian school on Saturdays, I would eat Lithuanian-style potato pancakes. My grandfather, Jonas Noreika, was a particularly important part of my family story: He was the mastermind of a 1945-1946 revolt against the Soviet Union, and was executed. A picture of him in his military uniform hung in our living room. Today, he is a hero not just in my family. He has streets, plaques and a school named after him. He was awarded the Cross of the Vytis, Lithuania’s highest posthumous honor.

On her deathbed in 2000, my mother asked me to take over writing a book about her father. I eagerly agreed. But as I sifted through the material, I came across a document with his signature from 1941 and everything changed. The story of my grandfather was much darker than I had known. I learned that the man I had believed was a savior who did all he could to rescue Jews during World War II had, in reality, ordered all Jews in his region of Lithuania to be rounded up and sent to a ghetto where they were beaten, starved, tortured, raped and then murdered. More than 95 percent of Lithuania’s Jews died during World War II, many of them killed with the eager collaboration of their neighbors.

More here.

In communicating with Carolee Schneemann in the last months of her life there was a sense that the artist was in a race against time. Schneemann — now regarded as one of the most important artists of the 20th century — knew that death was approaching and there was still so much to clear up, to articulate and to preserve. In the last years before her passing in 2019, Schneemann had finally overcome decades of rejection and neglect of her work to receive the art world’s recognition and adulation in its fullness. There were major retrospectives at the Museum der Moderne Salzburg, the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt, and MoMA Ps1 in New York. In 2017, Schneemann received the Golden Lion award for lifetime achievement at the Venice Biennale. And yet it wasn’t always easy for the artist to enjoy this newfound respect. The path had been hard.

In communicating with Carolee Schneemann in the last months of her life there was a sense that the artist was in a race against time. Schneemann — now regarded as one of the most important artists of the 20th century — knew that death was approaching and there was still so much to clear up, to articulate and to preserve. In the last years before her passing in 2019, Schneemann had finally overcome decades of rejection and neglect of her work to receive the art world’s recognition and adulation in its fullness. There were major retrospectives at the Museum der Moderne Salzburg, the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt, and MoMA Ps1 in New York. In 2017, Schneemann received the Golden Lion award for lifetime achievement at the Venice Biennale. And yet it wasn’t always easy for the artist to enjoy this newfound respect. The path had been hard. When your anger won’t play well with the anger of others—when it turns down invitations to surface, and persists despite the absence of company—you frequently find yourself on the receiving end of attempts at anger management. Sometimes these conversations can be settled by the introduction of new information or the correction of a misperception, but when those strategies fail, they often devolve into a pure emotional tug-of-war in which you hear that your anger is unproductive; that it’s time to move on; that we are ultimately on the same team. Or, alternatively—for this, too, is “anger management,” though it isn’t usually called that—you hear that if you’re not angry, you’re not paying attention; that unless you’re with us, you’re against us.

When your anger won’t play well with the anger of others—when it turns down invitations to surface, and persists despite the absence of company—you frequently find yourself on the receiving end of attempts at anger management. Sometimes these conversations can be settled by the introduction of new information or the correction of a misperception, but when those strategies fail, they often devolve into a pure emotional tug-of-war in which you hear that your anger is unproductive; that it’s time to move on; that we are ultimately on the same team. Or, alternatively—for this, too, is “anger management,” though it isn’t usually called that—you hear that if you’re not angry, you’re not paying attention; that unless you’re with us, you’re against us. What is it like to be a bat? It might seem a silly question, but as I start my new series in which I imagine my way into various animals’ heads, it is a perfect starting point. Why? Because it is a silly question that has taken up an enormous amount of earnest intellectual energy ever since the American philosopher Thomas Nagel first posed it in a celebrated 1974 paper.

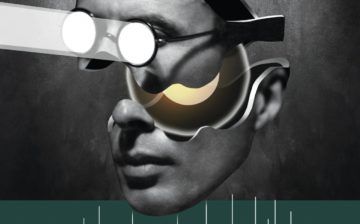

What is it like to be a bat? It might seem a silly question, but as I start my new series in which I imagine my way into various animals’ heads, it is a perfect starting point. Why? Because it is a silly question that has taken up an enormous amount of earnest intellectual energy ever since the American philosopher Thomas Nagel first posed it in a celebrated 1974 paper. In the mid-Sixties the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum created the first artificial intelligence chatbot, named Eliza, after Eliza Doolittle. Eliza was programmed to respond to users in the manner of a Rogerian therapist – reflecting their responses back to them or asking general, open-ended questions. “Tell me more,” Eliza might say. Weizenbaum was alarmed by how rapidly users grew attached to Eliza. “Extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people,” he wrote. It disturbed him that humans were so easily manipulated.

In the mid-Sixties the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum created the first artificial intelligence chatbot, named Eliza, after Eliza Doolittle. Eliza was programmed to respond to users in the manner of a Rogerian therapist – reflecting their responses back to them or asking general, open-ended questions. “Tell me more,” Eliza might say. Weizenbaum was alarmed by how rapidly users grew attached to Eliza. “Extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people,” he wrote. It disturbed him that humans were so easily manipulated. As long as vaccines have existed, humans have been suspicious of both the shots and those who administer them. The first inoculation deployed in America, against smallpox in the 1720s, was decried as antithetical to God’s will. An outraged citizen

As long as vaccines have existed, humans have been suspicious of both the shots and those who administer them. The first inoculation deployed in America, against smallpox in the 1720s, was decried as antithetical to God’s will. An outraged citizen  For 7 years as president of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Robert Tjian helped steer hundreds of millions of dollars to scientists probing provocative ideas that might transform biology and biomedicine. So the biochemist was intrigued a couple of years ago when his graduate student David McSwiggen uncovered data likely to fuel excitement about a process called phase separation, already one of the hottest concepts in cell biology.

For 7 years as president of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Robert Tjian helped steer hundreds of millions of dollars to scientists probing provocative ideas that might transform biology and biomedicine. So the biochemist was intrigued a couple of years ago when his graduate student David McSwiggen uncovered data likely to fuel excitement about a process called phase separation, already one of the hottest concepts in cell biology. To observers of the American class system in the 21st century, the common conflation of social class with income is a source of amusement as well as frustration. Depending on how you slice and dice the population, you can come up with as many income classes as you like—four classes with 25%, or the 99% against the 1%, or the 99.99% against the 0.01%. In the United States, as in most advanced societies, class tends to be a compound of income, wealth, education, ethnicity, religion, and race, in various proportions. There has never been a society in which the ruling class consisted merely of a basket of random rich people.

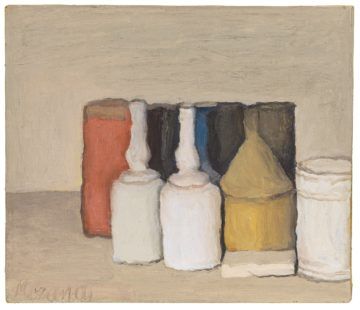

To observers of the American class system in the 21st century, the common conflation of social class with income is a source of amusement as well as frustration. Depending on how you slice and dice the population, you can come up with as many income classes as you like—four classes with 25%, or the 99% against the 1%, or the 99.99% against the 0.01%. In the United States, as in most advanced societies, class tends to be a compound of income, wealth, education, ethnicity, religion, and race, in various proportions. There has never been a society in which the ruling class consisted merely of a basket of random rich people. Imagine bits of wood trapped in eddies of a stream, going round and round atop the waters that flow beneath them. The image comes to mind in response to a surprising show—surprisingly great, contrary to my skeptical expectation—at

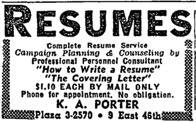

Imagine bits of wood trapped in eddies of a stream, going round and round atop the waters that flow beneath them. The image comes to mind in response to a surprising show—surprisingly great, contrary to my skeptical expectation—at  For as long as we have been writing cover letters, or covering letters, and whatever preceded covering letters, writers have sought the support of those who have mastered the craft du jour. Lurie describes what he believes is the earliest example of an advertisement for how-to guides on writing “cover letters.” He says, “The first true sign that cover letters were mainstream enough to cause job applicants some anxiety was an advertisement in 1965, in the Boston Globe.” Again, it should come as no surprise, that one will find an advertisement for a how-to guide on “the covering letter” (again in the New York Times) in August 1955—more than a decade before the example that Mr. Lurie cites in the Boston Globe, and indeed much closer to the pair of Dutch Boy ads.

For as long as we have been writing cover letters, or covering letters, and whatever preceded covering letters, writers have sought the support of those who have mastered the craft du jour. Lurie describes what he believes is the earliest example of an advertisement for how-to guides on writing “cover letters.” He says, “The first true sign that cover letters were mainstream enough to cause job applicants some anxiety was an advertisement in 1965, in the Boston Globe.” Again, it should come as no surprise, that one will find an advertisement for a how-to guide on “the covering letter” (again in the New York Times) in August 1955—more than a decade before the example that Mr. Lurie cites in the Boston Globe, and indeed much closer to the pair of Dutch Boy ads. One relevant fact is that people over 65 have a higher risk of dying from COVID-19 than younger people do, and those over 75 are at even higher risk.

One relevant fact is that people over 65 have a higher risk of dying from COVID-19 than younger people do, and those over 75 are at even higher risk. The possible existence of technologically advanced extraterrestrial civilizations — not just alien microbes, but cultures as advanced (or much more) than our own — is one of the most provocative questions in modern science. So provocative that it’s difficult to talk about the idea in a rational, dispassionate way; there are those who loudly insist that the probability of advanced alien cultures existing is essentially one, even without direct evidence, and others are so exhausted by overblown claims in popular media that they want to squelch any such talk. Astronomer Avi Loeb thinks we should be taking this possibility seriously, so much so that he suggested that the recent interstellar interloper

The possible existence of technologically advanced extraterrestrial civilizations — not just alien microbes, but cultures as advanced (or much more) than our own — is one of the most provocative questions in modern science. So provocative that it’s difficult to talk about the idea in a rational, dispassionate way; there are those who loudly insist that the probability of advanced alien cultures existing is essentially one, even without direct evidence, and others are so exhausted by overblown claims in popular media that they want to squelch any such talk. Astronomer Avi Loeb thinks we should be taking this possibility seriously, so much so that he suggested that the recent interstellar interloper  Our differences over policy are substantial, but they’re

Our differences over policy are substantial, but they’re  I

I  JERUSALEM — Israel, which leads the world in vaccinating its population against the coronavirus, has produced some encouraging news: Early results show a significant drop in infection after just one shot of a two-dose vaccine, and better than expected results after both doses. Public health experts caution that the data, based on the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, is preliminary and has not been subjected to clinical trials. Even so, Dr. Anat Ekka Zohar, vice president of Maccabi Health Services, one of the Israeli health maintenance organizations that released the data, called it “very encouraging.” In the first early report, Clalit, Israel’s largest health fund, compared 200,000 people aged 60 or over who received a first dose of the vaccine to a matched group of 200,000 who had not been vaccinated yet. It said that 14 to 18 days after their shots, the partially vaccinated patients were

JERUSALEM — Israel, which leads the world in vaccinating its population against the coronavirus, has produced some encouraging news: Early results show a significant drop in infection after just one shot of a two-dose vaccine, and better than expected results after both doses. Public health experts caution that the data, based on the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, is preliminary and has not been subjected to clinical trials. Even so, Dr. Anat Ekka Zohar, vice president of Maccabi Health Services, one of the Israeli health maintenance organizations that released the data, called it “very encouraging.” In the first early report, Clalit, Israel’s largest health fund, compared 200,000 people aged 60 or over who received a first dose of the vaccine to a matched group of 200,000 who had not been vaccinated yet. It said that 14 to 18 days after their shots, the partially vaccinated patients were