Ann Wroe in 1843 Magazine:

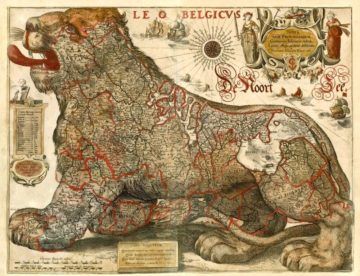

In spring thoughts traditionally turn to travelling, and so to maps. This was always something of a ritual in our house. Out of the bottom desk-drawer they’d come: the shiny Ordnance Surveys, the dog-eared city guides, the family treasures backed with canvas or patched with tape. Into the glove-compartment some would go, among the pens and receipts and whitening chocolate bars. We were halfway there already. Last year’s road map, already in a tattered state, would be thrown on the back seat. We had much less affection for that. Like the pale, flat Google Maps now on our phones, or the relentless black curve of the SatNav, this was a dull thing.

In spring thoughts traditionally turn to travelling, and so to maps. This was always something of a ritual in our house. Out of the bottom desk-drawer they’d come: the shiny Ordnance Surveys, the dog-eared city guides, the family treasures backed with canvas or patched with tape. Into the glove-compartment some would go, among the pens and receipts and whitening chocolate bars. We were halfway there already. Last year’s road map, already in a tattered state, would be thrown on the back seat. We had much less affection for that. Like the pale, flat Google Maps now on our phones, or the relentless black curve of the SatNav, this was a dull thing.

…Old maps assume that travel will be difficult, but they give it interest. The roads that meander through 17th-century county maps pass small pyramidal hills, copses, settlements and steeples, which look worth a visit. On medieval maps what seem to be roads may actually be rivers, snaking to alarming dead ends – you’ll be well-mired and stranded whichever way you go. Yet here is a building with turrets and vanes, there a train of laden camels, over there a Great Khan with turban and beard sitting, in a welcoming way, under a striped pavilion. And out in the sea great whales are surfacing and blowing.

Modern 1:25,000 maps have much the same allure.

More here.

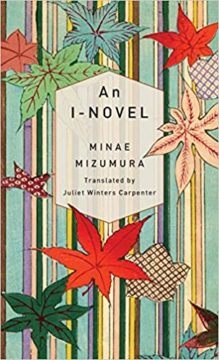

For generations, Anna Karenina and Emma Bovary have loomed as the nonpareils of self-loathing literary heroines. For Anna, guilt over having abandoned her husband and child, paired with a jealous nature, compels her to destroy the love she shares with Count Vronsky — and head for the train tracks. For Emma, dumped by a conscience-free bachelor with whom she has an extramarital affair — and unable to repay the debts she accrues on account of her shopping addiction — a spoonful of arsenic ultimately beckons. Lately, however, Tolstoy and Flaubert have had stiff competition on the self-harm front, thanks to women novelists intent on exploring their female characters’ propensity to act out their unhappiness on their bodies.

For generations, Anna Karenina and Emma Bovary have loomed as the nonpareils of self-loathing literary heroines. For Anna, guilt over having abandoned her husband and child, paired with a jealous nature, compels her to destroy the love she shares with Count Vronsky — and head for the train tracks. For Emma, dumped by a conscience-free bachelor with whom she has an extramarital affair — and unable to repay the debts she accrues on account of her shopping addiction — a spoonful of arsenic ultimately beckons. Lately, however, Tolstoy and Flaubert have had stiff competition on the self-harm front, thanks to women novelists intent on exploring their female characters’ propensity to act out their unhappiness on their bodies.

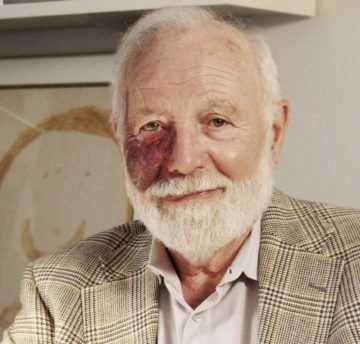

The mathematics community lost a titan with the passing last month of Isadore “Is” Singer. Born in Detroit in 1924, Is was a visionary, transcending divisions between fields of mathematics as well as those between mathematics and quantum physics. He pursued deep questions and inspired others in his original research, wide-ranging lectures, mentoring of young researchers and advocacy in the public sphere.

The mathematics community lost a titan with the passing last month of Isadore “Is” Singer. Born in Detroit in 1924, Is was a visionary, transcending divisions between fields of mathematics as well as those between mathematics and quantum physics. He pursued deep questions and inspired others in his original research, wide-ranging lectures, mentoring of young researchers and advocacy in the public sphere. A distinguishing mark of classical political philosophy is its focus on the ruling claims of regimes. Classical philosophers sifted and evaluated the distinctive qualities invoked to legitimate governance by some number of

A distinguishing mark of classical political philosophy is its focus on the ruling claims of regimes. Classical philosophers sifted and evaluated the distinctive qualities invoked to legitimate governance by some number of  Shortly after 335 B.C., within a newly built library tucked just east of Athens’ limestone city walls, a free-thinking Greek polymath by the name of Aristotle gathered up an armful of old theater scripts. As he pored over their delicate papyrus in the amber flicker of a sesame lamp, he was struck by a revolutionary idea: What if literature was an invention for making us happier and healthier? The idea made intuitive sense; when people felt bored, or unhappy, or at a loss for meaning, they frequently turned to plays or poetry. And afterwards, they often reported feeling better. But what could be the secret to literature’s feel-better power? What hidden nuts-and-bolts conveyed its psychological benefits?

Shortly after 335 B.C., within a newly built library tucked just east of Athens’ limestone city walls, a free-thinking Greek polymath by the name of Aristotle gathered up an armful of old theater scripts. As he pored over their delicate papyrus in the amber flicker of a sesame lamp, he was struck by a revolutionary idea: What if literature was an invention for making us happier and healthier? The idea made intuitive sense; when people felt bored, or unhappy, or at a loss for meaning, they frequently turned to plays or poetry. And afterwards, they often reported feeling better. But what could be the secret to literature’s feel-better power? What hidden nuts-and-bolts conveyed its psychological benefits? “That’s really all I write about, is hope and despair,” says Anne Lamott. Clearly, she was born into the era she was meant for. The bestselling author of durable classics like “Bird by Bird” and “Operating Instructions” is back once more with a new book, a new(ish) marriage and very much the same curiosity, humanity and sense of humor that been her brand for nearly 30 years.

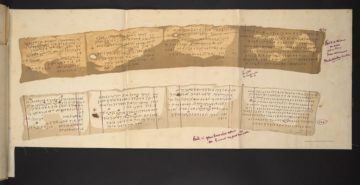

“That’s really all I write about, is hope and despair,” says Anne Lamott. Clearly, she was born into the era she was meant for. The bestselling author of durable classics like “Bird by Bird” and “Operating Instructions” is back once more with a new book, a new(ish) marriage and very much the same curiosity, humanity and sense of humor that been her brand for nearly 30 years.  In 1883, a Jerusalem antiquities dealer named Moses Wilhelm Shapira announced the discovery of a remarkable artifact: 15 manuscript fragments, supposedly discovered in a cave near the Dead Sea. Blackened with a pitchlike substance, their paleo-Hebrew script nearly illegible, they contained what Shapira claimed was the “original” Book of Deuteronomy, perhaps even Moses’ own copy.

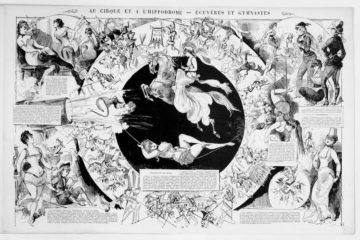

In 1883, a Jerusalem antiquities dealer named Moses Wilhelm Shapira announced the discovery of a remarkable artifact: 15 manuscript fragments, supposedly discovered in a cave near the Dead Sea. Blackened with a pitchlike substance, their paleo-Hebrew script nearly illegible, they contained what Shapira claimed was the “original” Book of Deuteronomy, perhaps even Moses’ own copy. There is a dual quality to Émilie’s life at this time: her bravado in the ring and her celebrity are ranged against repeated accounts of a modest, single-minded loner. After her mother’s death in 1880 and Clotilde’s retirement from the circus, she traveled only with a maid and a huge, white shaggy dog called Turc who followed her everywhere and slept at the foot of her bed. She would live alone in a small apartment near the circus at which she was engaged, and was said to enjoy books, music, and art, and receive few guests. She would only permit admirers to give her flowers—she had no interest in jewelry or more lucrative tokens. When her followers crammed into the circus stables to see her, she offered them only “banal” smiles calculated to be polite but not enticing. Not that that mattered. The circus managers issued invitations to every aristocrat in town as soon as her first performance was scheduled, feeding on Clotilde’s notoriety. Some of the writing about her is feverish: “Our little queen!” “The most beautiful will-o-the-wisp anyone could imagine!” “A female centaur!” “The diva of equitation, the Patti of haute école, the most intrepid amazone, the most charming, the most dizzying experience since the advent of the Amazons!”

There is a dual quality to Émilie’s life at this time: her bravado in the ring and her celebrity are ranged against repeated accounts of a modest, single-minded loner. After her mother’s death in 1880 and Clotilde’s retirement from the circus, she traveled only with a maid and a huge, white shaggy dog called Turc who followed her everywhere and slept at the foot of her bed. She would live alone in a small apartment near the circus at which she was engaged, and was said to enjoy books, music, and art, and receive few guests. She would only permit admirers to give her flowers—she had no interest in jewelry or more lucrative tokens. When her followers crammed into the circus stables to see her, she offered them only “banal” smiles calculated to be polite but not enticing. Not that that mattered. The circus managers issued invitations to every aristocrat in town as soon as her first performance was scheduled, feeding on Clotilde’s notoriety. Some of the writing about her is feverish: “Our little queen!” “The most beautiful will-o-the-wisp anyone could imagine!” “A female centaur!” “The diva of equitation, the Patti of haute école, the most intrepid amazone, the most charming, the most dizzying experience since the advent of the Amazons!” In 1768, the German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder paid a visit to the French city of Nantes. “I am getting to know the French language and ways of thinking,” he wrote to fellow-philosopher Johann Georg Hamann. But, “the closer my acquaintance with them is, the greater my sense of alienation becomes”.

In 1768, the German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder paid a visit to the French city of Nantes. “I am getting to know the French language and ways of thinking,” he wrote to fellow-philosopher Johann Georg Hamann. But, “the closer my acquaintance with them is, the greater my sense of alienation becomes”. …although I’ve written tens of thousands

…although I’ve written tens of thousands  I entered Martin Gurri’s world on August 1, 2015. Though I hadn’t read

I entered Martin Gurri’s world on August 1, 2015. Though I hadn’t read  “Kan kun være malet af en gal Mand!” (“Can only have been painted by a madman!”) appears on Norwegian artist Edvard Munch’s most famous painting The Scream.

“Kan kun være malet af en gal Mand!” (“Can only have been painted by a madman!”) appears on Norwegian artist Edvard Munch’s most famous painting The Scream.  One of the oldest imperatives of American electoral politics is to define your opponents before they can define themselves. So it was not surprising when, in the summer of 1963, Nelson Rockefeller, a centrist Republican governor from New York, launched a preëmptive attack against Barry Goldwater, a right-wing Arizona senator, as both men were preparing to run for the Presidential nomination of the Republican Party. But the nature of Rockefeller’s attack was noteworthy. If the G.O.P. embraced Goldwater, an opponent of civil-rights legislation, Rockefeller suggested that it would be pursuing a “program based on racism and sectionalism.” Such a turn toward the elements that Rockefeller saw as “fantastically short-sighted” would be potentially destructive to a party that had held the White House for eight years, owing to the popularity of Dwight Eisenhower, but had been languishing in the minority in Congress for the better part of three decades. Some moderates in the Republican Party thought that Rockefeller was overstating the threat, but he was hardly alone in his concern. Richard Nixon, the former Vice-President, who had received substantial Black support in his 1960 Presidential bid, against John F. Kennedy, told a reporter for Ebony that “if Goldwater wins his fight, our party would eventually become the first major all-white political party.” The Chicago Defender, the premier Black newspaper of the era, concurred, stating bluntly that the G.O.P. was en route to becoming a “white man’s party.”

One of the oldest imperatives of American electoral politics is to define your opponents before they can define themselves. So it was not surprising when, in the summer of 1963, Nelson Rockefeller, a centrist Republican governor from New York, launched a preëmptive attack against Barry Goldwater, a right-wing Arizona senator, as both men were preparing to run for the Presidential nomination of the Republican Party. But the nature of Rockefeller’s attack was noteworthy. If the G.O.P. embraced Goldwater, an opponent of civil-rights legislation, Rockefeller suggested that it would be pursuing a “program based on racism and sectionalism.” Such a turn toward the elements that Rockefeller saw as “fantastically short-sighted” would be potentially destructive to a party that had held the White House for eight years, owing to the popularity of Dwight Eisenhower, but had been languishing in the minority in Congress for the better part of three decades. Some moderates in the Republican Party thought that Rockefeller was overstating the threat, but he was hardly alone in his concern. Richard Nixon, the former Vice-President, who had received substantial Black support in his 1960 Presidential bid, against John F. Kennedy, told a reporter for Ebony that “if Goldwater wins his fight, our party would eventually become the first major all-white political party.” The Chicago Defender, the premier Black newspaper of the era, concurred, stating bluntly that the G.O.P. was en route to becoming a “white man’s party.”