Category: Recommended Reading

Poland’s Forgotten Bohemian War Hero

Marta Figlerowicz in Boston Review:

Marta Figlerowicz in Boston Review:

The life of Polish artist and diplomat Józef Czapski (1896–1993) in many ways mirrored the intellectual trajectory of twentieth-century Europe. Yet readers have likely never heard of him. That is in part because, despite being exemplary, Czapski’s work is hard to contextualize. It does not fit neatly as either prewar or postwar. Instead, it reveals an old world still present in the new and seeking to understand what it had become. With new translations of Czapski’s writing and a wonderful new biography by Eric Karpeles, Czapski comes alive for English readers with a depth and clarity previously absent. One can hope, then, that the time for Czapski’s revival has come.

Czapski was a gifted painter but also a compulsive, talented diarist and essayist. In the salons of Europe, Russia, and North America, he mingled with the likes of Gertrude Stein, Pablo Picasso, André Gide, and Anna Akhmatova; Czapski even appears, in a romantic light, in one of the latter’s poems. Over the years, he had relationships with both men and women, including Canadian heiresses and the younger brother of Vladimir Nabokov.

Born in Prague into an aristocratic family, the young Count Hutten-Czapski spoke German with his mother and French with his governess. He briefly studied law at the Imperial College in St. Petersburg before moving to the newly independent Poland to become an artist. Czapski soon dropped his title and the Germanic surname Hutten; as Józio Czapski, he then moved to Paris with a group of his painter friends, where they lived on a shoestring budget with little support from their families.

More here.

Larry McMurtry’s Irresistible, Inexhaustible Stories

Rick Bragg at the LA Times:

McMurtry, who died last week, was described in one obit as among the most acclaimed writers of the American experience. A long time ago, he wrote a few kind words to me about a book I wrote, so, of course, I was predisposed to love his work; writers are whores that way.

McMurtry, who died last week, was described in one obit as among the most acclaimed writers of the American experience. A long time ago, he wrote a few kind words to me about a book I wrote, so, of course, I was predisposed to love his work; writers are whores that way.

But he could have called me a low-down, sorry S.O.B and I still would have read pretty much everything he wrote. If the point of a good book is to vanish into it, then he was one of the best there ever was. And I always knew, in a world of wasted time, that I hadn’t wasted a second.

Few writers I have ever read breathed such life into words. He showed us the wisdom of Sam the Lion in “The Last Picture Show” and the rage of Woodrow Call and the broken, wandering heart of Augustus McCrae in “Lonesome Dove.”

more here.

Saturday Poem

Allegro Ma Non Troppo

Life, you’re beautiful (I say)

you just couldn’t get more fecund,

more befrogged or nightingailey,

more anthillful or sproutspouting.

I’m trying to court life’s favour,

to get into its good graces,

to anticipate its whims.

I’m always the first to bow,

always there where it can see me

with my humble, reverent face,

soaring on the wings of rapture,

falling under waves of wonder.

Oh how grassy is this hopper,

How his berry ripely rasps.

I would never have conceived it

if I weren’t conceived myself!

Life (I say) I’ve no idea

what I could compare you to.

No one else can make a pine cone

and then make the pine cone’s clone.

I praise your inventiveness,

bounty, sweep, exactitude,

sense of order – gifts that border

on witchcraft and wizardry.

I just don’t want to upset you,

tease or anger, vex or rile.

For millennia, I’ve been trying

to appease you with my smile.

I tug at life by its leaf hem:

will it stop for me, just once,

momentarily forgetting

to what end it runs and runs?

by Wislawa Szymborska

from View With a Grain of Sand

Harcourt Brace 1993

India is no longer the country of this novel

Salman Rushdie in The Guardian:

Forty years is a long time. I have to say that India is no longer the country of this novel. When I wrote Midnight’s Children I had in mind an arc of history moving from the hope – the bloodied hope, but still the hope – of independence to the betrayal of that hope in the so-called Emergency, followed by the birth of a new hope. India today, to someone of my mind, has entered an even darker phase than the Emergency years. The horrifying escalation of assaults on women, the increasingly authoritarian character of the state, the unjustifiable arrests of people who dare to stand against that authoritarianism, the religious fanaticism, the rewriting of history to fit the narrative of those who want to transform India into a Hindu-nationalist, majoritarian state, and the popularity of the regime in spite of it all, or, worse, perhaps because of it all – these things encourage a kind of despair.

Forty years is a long time. I have to say that India is no longer the country of this novel. When I wrote Midnight’s Children I had in mind an arc of history moving from the hope – the bloodied hope, but still the hope – of independence to the betrayal of that hope in the so-called Emergency, followed by the birth of a new hope. India today, to someone of my mind, has entered an even darker phase than the Emergency years. The horrifying escalation of assaults on women, the increasingly authoritarian character of the state, the unjustifiable arrests of people who dare to stand against that authoritarianism, the religious fanaticism, the rewriting of history to fit the narrative of those who want to transform India into a Hindu-nationalist, majoritarian state, and the popularity of the regime in spite of it all, or, worse, perhaps because of it all – these things encourage a kind of despair.

When I wrote this book I could associate big-nosed Saleem with the elephant-trunked god Ganesh, the patron deity of literature, among other things, and that felt perfectly easy and natural even though Saleem was not a Hindu. All of India belonged to all of us, or so I deeply believed. And still believe, even though the rise of a brutal sectarianism believes otherwise. But I find hope in the determination of India’s women and college students to resist that sectarianism, to reclaim the old, secular India and dismiss the darkness. I wish them well. But right now, in India, it’s midnight again.

More here.

What Does It Mean to Be a Living Thing?

Siddhartha Mukherjee in The New York Times:

Carl Zimmer’s book begins with a bang. Not a Big Bang, but a small one. In the fall of 1904, a 31-year-old physicist, John Butler Burke, working at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge University, made a “bouillon” of chunks of boiled beef in water. To this mix, he added a dab of radium, the newly discovered element glowing with radioactive energy, and waited overnight. The next morning, he skimmed the radioactive soup, smeared a layer on a glass slide and placed it under a microscope. He saw spicules of coalesced matter — “radiobes,” as he called them — that resembled, to his eyes, the most primeval forms of life.

Carl Zimmer’s book begins with a bang. Not a Big Bang, but a small one. In the fall of 1904, a 31-year-old physicist, John Butler Burke, working at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge University, made a “bouillon” of chunks of boiled beef in water. To this mix, he added a dab of radium, the newly discovered element glowing with radioactive energy, and waited overnight. The next morning, he skimmed the radioactive soup, smeared a layer on a glass slide and placed it under a microscope. He saw spicules of coalesced matter — “radiobes,” as he called them — that resembled, to his eyes, the most primeval forms of life.

He was convinced that he had made a major discovery. “They are entitled to be classed among living things,” he would later write. It was heralded as a monumental advance — noted in newspapers and scientific journals. That December, black-tied physicists from the Cavendish gathered to celebrate Burke’s astonishing achievement. They sang:

Through me they say life was created

And animals formed out of clay,

With bouillon I’m told I was mated

And started the life of today.

Burke’s fall from fame, unfortunately, would be as precipitous as his rise. His “radiobes” would later turn out to have little to do with living chemicals, or life. But Burke, convinced that he had discovered “artificial life” and potentially shed light on life’s origins (make soup, throw in radioactivity, then just add water), turned into a ridiculous crank. Brushed off by the scientific community, this fleeting star of biology would die, impoverished and ranting about how his “radiobes” held the clue to life. He would eventually become the butt of scientific jokes — the modern version of the medieval alchemist who was once convinced that a mixture of semen and rotting meat, incubated in a warm hole, could spontaneously form a homunculus, a miniature human.

More here.

Friday, April 2, 2021

From the Faraway Nearby

Morgan Meis in Image:

The continuity stretching from the earlier flower and plant paintings to the landscape work in New Mexico comes from O’Keeffe’s lifelong obsession with looking at things. I mean that quite literally. How do you look at a thing? How do you see a thing? Well, you just look, don’t you? But O’Keeffe’s answer is, “No, you don’t just look, because you don’t know how to look.” So what’s the difference between looking in the normal way and looking in the O’Keeffe way? Much of it has to do with time. O’Keeffe liked to look at things for a long time. She’d stare at a single flower over and over again, hour after hour. We think we know what that means. But do we? I suspect the actual experience is crucial here. That’s to say, don’t assume you know what it means to look at one thing hour after hour unless you’ve done it. I’ve done it, sort of. I stared at a flower once more or less without interruption for over an hour. It was immensely difficult for the first twenty minutes or so. Then something changed. My vision started to surrender to something else. Everything suddenly slowed down and intensified. I started to see the flower as a whole, as well as the tiny individual parts, simultaneously. A kind of meditational state kicked in. My vision became a form, almost, of physical touching. It was sensuous and sensual, which is why all the critics who’ve talked about the sensuality of O’Keeffe’s flower paintings are not completely wrong.

The continuity stretching from the earlier flower and plant paintings to the landscape work in New Mexico comes from O’Keeffe’s lifelong obsession with looking at things. I mean that quite literally. How do you look at a thing? How do you see a thing? Well, you just look, don’t you? But O’Keeffe’s answer is, “No, you don’t just look, because you don’t know how to look.” So what’s the difference between looking in the normal way and looking in the O’Keeffe way? Much of it has to do with time. O’Keeffe liked to look at things for a long time. She’d stare at a single flower over and over again, hour after hour. We think we know what that means. But do we? I suspect the actual experience is crucial here. That’s to say, don’t assume you know what it means to look at one thing hour after hour unless you’ve done it. I’ve done it, sort of. I stared at a flower once more or less without interruption for over an hour. It was immensely difficult for the first twenty minutes or so. Then something changed. My vision started to surrender to something else. Everything suddenly slowed down and intensified. I started to see the flower as a whole, as well as the tiny individual parts, simultaneously. A kind of meditational state kicked in. My vision became a form, almost, of physical touching. It was sensuous and sensual, which is why all the critics who’ve talked about the sensuality of O’Keeffe’s flower paintings are not completely wrong.

More here.

Machine-Learning Pioneer: Stop Calling Everything AI

Kathy Pretz in IEEE Spectrum:

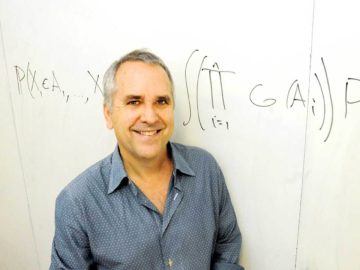

Artificial-intelligence systems are nowhere near advanced enough to replace humans in many tasks involving reasoning, real-world knowledge, and social interaction. They are showing human-level competence in low-level pattern recognition skills, but at the cognitive level they are merely imitating human intelligence, not engaging deeply and creatively, says Michael I. Jordan, a leading researcher in AI and machine learning. Jordan is a professor in the department of electrical engineering and computer science, and the department of statistics, at the University of California, Berkeley.

Artificial-intelligence systems are nowhere near advanced enough to replace humans in many tasks involving reasoning, real-world knowledge, and social interaction. They are showing human-level competence in low-level pattern recognition skills, but at the cognitive level they are merely imitating human intelligence, not engaging deeply and creatively, says Michael I. Jordan, a leading researcher in AI and machine learning. Jordan is a professor in the department of electrical engineering and computer science, and the department of statistics, at the University of California, Berkeley.

He notes that the imitation of human thinking is not the sole goal of machine learning—the engineering field that underlies recent progress in AI—or even the best goal. Instead, machine learning can serve to augment human intelligence, via painstaking analysis of large data sets in much the way that a search engine augments human knowledge by organizing the Web. Machine learning also can provide new services to humans in domains such as health care, commerce, and transportation, by bringing together information found in multiple data sets, finding patterns, and proposing new courses of action.

More here.

Thomas Sowell: Tragic Optimist

Samuel Kronen in Quillette:

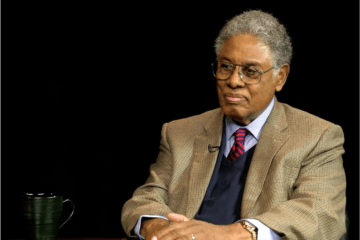

Somewhere out of the mysterious interplay between nature and nurture, internal and external factors, cultures and structures, and bottom-up and top-down forces there emerge the individual and group outcomes that we care about and which ultimately make the difference between human flourishing and its absence. What distinguishes various political ideologies, in effect, is how the line of causation is drawn, or, more specifically, from which direction. What gets left unexamined in the rush for compelling narratives and ideological certainty, however, is the territory between different causes and how they combine to shape reality. Few have gone further to map that territory than the American economist, political philosopher, and public intellectual Thomas Sowell.

Somewhere out of the mysterious interplay between nature and nurture, internal and external factors, cultures and structures, and bottom-up and top-down forces there emerge the individual and group outcomes that we care about and which ultimately make the difference between human flourishing and its absence. What distinguishes various political ideologies, in effect, is how the line of causation is drawn, or, more specifically, from which direction. What gets left unexamined in the rush for compelling narratives and ideological certainty, however, is the territory between different causes and how they combine to shape reality. Few have gone further to map that territory than the American economist, political philosopher, and public intellectual Thomas Sowell.

At 90 years of age, Sowell remains among the most prolific, influential, and penetrating minds of the past century. He understands the world in terms of trade-offs, incentives, constraints, systemic processes, feedback mechanisms, and human capital, an understanding developed by scrutinizing available data, considering human experience, and applying robust common sense.

More here.

Nawal El Saadawi (RIP), Egyptian writer, doctor, feminist, and activist, in conversation with Kenan Malik in 2015

Friday Poem

In Praise of Dreams

In my dreams

I paint like Vermeer van Delft.

I speak fluent Greek

and not just with the living.

I drive a car

that does what I want it to.

I am gifted

and write mighty epics.

I hear voices

as clearly as any venerable saint.

My brilliance as a pianist

would stun you.

I fly the way we ought to,

i.e., on my own.

Falling from the roof,

I tumble gently to the grass.

I’ve got no problem

breathing under water.

I can’t complain:

I’ve been able to locate Atlantis.

It’s gratifying that I can always

wake up before dying.

As soon as war breaks out,

I roll over on my other side.

I’m a child of my age,

but I don’t have to be.

A few years ago

I saw two suns.

And the night before last a penguin,

clear as day.

by Wislawa Szymborska

from View with a Grain of Sand

Harcourt Brace, 1995

In Search of the Authentic Ernest Hemingway

Elizabeth Djinis in Smithsonian:

Ernest Hemingway had a version of himself that he wanted us to see—the avid fisher and outdoorsman, the hyper-masculine writer, the man whose friends called him “Papa.” Then, there was the hidden Hemingway—vulnerable, sensitive and longing for connection. The two were not mutually exclusive, and in his work and his life, they often intersected.

More than anything, Hemingway’s external legacy is connected to his revolutionary writing. His declarative writing style was innovative, getting to the truth of the matter in as few words as possible. But his life attracted almost as much attention as his work. The legend came of age in 1920s Paris, a time where a salon gathering might attract such giants as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein and James Joyce, and he later took up notable residence at homes in Key West and Cuba. Hemingway published more than nine novels and collections of short stories in his lifetime, many of them examinations of war set in Europe. Among the most famous are For Whom The Bell Tolls, The Sun Also Rises and To Have and Have Not. He won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1953 for The Old Man and the Sea, one of his last works to be published while still living. The following year, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature for his entire body of work. Out this month, April 5 through April 7 on PBS, is a new three-part documentary series directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, which delves into Hemingway’s legacy and challenges understandings of the man as writer and as artist. His stark prose, his outdoorsy and adventurous lifestyle and his journalistic and wartime beginnings all helped Hemingway come to represent a kind of orchestrated masculine ideal.

More here.

Study finds why some cancer drugs may be ineffective

Jeanette Sanchez in Phys.Org:

In the study, investigators reported the extensive presence of mouse viruses in patient-derived xenografts (PDX). PDX models are developed by implanting human tumor tissues in immune-deficient mice, and are commonly used to help test and develop cancer drugs.

In the study, investigators reported the extensive presence of mouse viruses in patient-derived xenografts (PDX). PDX models are developed by implanting human tumor tissues in immune-deficient mice, and are commonly used to help test and develop cancer drugs.

“What we found is that when you put a human tumor in a mouse, that tumor is not the same as the tumor that was in the cancer patient,” said W. Jim Zheng, Ph.D., professor at the School of Biomedical Informatics and senior author on the study. “The majority of tumors we tested were compromised by mouse viruses.” Using a data-driven approach, researchers analyzed 184 data sets generated from sequencing PDX samples. Of the 184 samples, 170 showed the presence of mouse viruses. The infection is associated with significant changes in tumors, and Zheng says that could affect PDX as a drug testing model for humans.

“When scientists are looking for a way to kill a tumor using the PDX model, they assume the tumor in the mouse is the same as cancer patients, but they are not. It makes the results of a cancer drug look promising when you think the medication kills the tumor—but in reality, it will not work in human trial, as the medication kills the virus-compromised tumor in mouse,” Zheng said.

More here.

Can’t Get You Out of My Head (2021) – Part 1: Bloodshed on Wolf Mountain

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MHFrhIAj0ME&t=308s

Are Some Virtues Casualties of Progress?

George Scialabba at Commonweal:

According to the late Christopher Lasch, the advent of mass production and the new relations of authority it introduced in every sphere of social life wrought a fateful change in the prevailing American character. Psychological maturation—as Lasch, relying on Freud, explicated it—depended crucially on face-to-face relations, on a rhythm and a scale that industrialism disrupted. The result was a weakened, malleable self, more easily regimented than its pre-industrial forebear, less able to withstand conformist pressures and bureaucratic manipulation—the antithesis of the rugged individualism that had undergirded the republican virtues.

According to the late Christopher Lasch, the advent of mass production and the new relations of authority it introduced in every sphere of social life wrought a fateful change in the prevailing American character. Psychological maturation—as Lasch, relying on Freud, explicated it—depended crucially on face-to-face relations, on a rhythm and a scale that industrialism disrupted. The result was a weakened, malleable self, more easily regimented than its pre-industrial forebear, less able to withstand conformist pressures and bureaucratic manipulation—the antithesis of the rugged individualism that had undergirded the republican virtues.

In an important recent book, The Age of Acquiescence, the historian Steve Fraser deploys a similar argument to explain why, in contrast with the first Gilded Age, when America was wracked by furious anti-capitalist resistance, popular response in our time to the depredations of capitalism has been so feeble.

more here.

The Musical Human: A History of Life on Earth

Mathew Lyons at Literary Review:

The first note known to have sounded on earth was an E natural. It was produced some 165 million years ago by a katydid (a kind of cricket) rubbing its wings together, a fact deduced by scientists from the remains of one of these insects, preserved in amber. Consider, too, the love life of the mosquito. When a male mosquito wishes to attract a mate, his wings buzz at a frequency of 600Hz, which is the equivalent of D natural. The normal pitch of the female’s wings is 400Hz, or G natural. Just prior to sex, however, male and female harmonise at 1200Hz, which is, as Michael Spitzer notes in his extraordinary new book, The Musical Human, ‘an ecstatic octave above the male’s D’. ‘Everything we sing’, Spitzer adds, ‘is just a footnote to that.’

The first note known to have sounded on earth was an E natural. It was produced some 165 million years ago by a katydid (a kind of cricket) rubbing its wings together, a fact deduced by scientists from the remains of one of these insects, preserved in amber. Consider, too, the love life of the mosquito. When a male mosquito wishes to attract a mate, his wings buzz at a frequency of 600Hz, which is the equivalent of D natural. The normal pitch of the female’s wings is 400Hz, or G natural. Just prior to sex, however, male and female harmonise at 1200Hz, which is, as Michael Spitzer notes in his extraordinary new book, The Musical Human, ‘an ecstatic octave above the male’s D’. ‘Everything we sing’, Spitzer adds, ‘is just a footnote to that.’

Humans may be the supremely musical animal, but, with or without us, this is a musical planet. What makes us special? The answer is complex.

more here.

Thursday, April 1, 2021

What happens to our cognition in the darkest depths of winter?

Tim Brennen in Psyche:

We tested 100 participants twice on a range of tests: some took them first in summer and then winter, and some in the opposite order. Among the tasks, there was a test of pure speed (‘press this button as quickly as possible as soon as you see a circle in the middle of the screen’); a test of immediate memory for digits; a test of memory for words presented 10 minutes previously; the classic ‘Stroop test’ (that measures mental control); an alertness task; a face-recognition task; a time-estimation task; and a verbal fluency task. Most tests showed no difference in performance between summer and winter, and, of those that did, four out of five actually suggested a winter advantage. The ‘Arctic cognition’ paper, as we called it in 2000, was disseminated over the whole world and had its 15 minutes of fame in newspapers and magazines.

We tested 100 participants twice on a range of tests: some took them first in summer and then winter, and some in the opposite order. Among the tasks, there was a test of pure speed (‘press this button as quickly as possible as soon as you see a circle in the middle of the screen’); a test of immediate memory for digits; a test of memory for words presented 10 minutes previously; the classic ‘Stroop test’ (that measures mental control); an alertness task; a face-recognition task; a time-estimation task; and a verbal fluency task. Most tests showed no difference in performance between summer and winter, and, of those that did, four out of five actually suggested a winter advantage. The ‘Arctic cognition’ paper, as we called it in 2000, was disseminated over the whole world and had its 15 minutes of fame in newspapers and magazines.

I moved on to other research topics, but last year, now working at the University of Oslo at a mere 59°N, I decided to revisit the science of human seasonality.

More here.

Mathematicians Find a New Class of Digitally Delicate Primes

Steve Nadis in Quanta:

Take a look at the numbers 294,001, 505,447 and 584,141. Notice anything special about them? You may recognize that they’re all prime — evenly divisible only by themselves and 1 — but these particular primes are even more unusual.

Take a look at the numbers 294,001, 505,447 and 584,141. Notice anything special about them? You may recognize that they’re all prime — evenly divisible only by themselves and 1 — but these particular primes are even more unusual.

If you pick any single digit in any of those numbers and change it, the new number is composite, and hence no longer prime. Change the 1 in 294,001 to a 7, for instance, and the resulting number is divisible by 7; change it to a 9, and it’s divisible by 3.

Such numbers are called “digitally delicate primes,” and they’re a relatively recent mathematical invention. In 1978, the mathematician and prolific problem poser Murray Klamkin wondered if any numbers like this existed. His question got a quick response from one of the most prolific problem solvers of all time, Paul Erdős. He proved not only that they do exist, but also that there are an infinite number of them — a result that holds not just for base 10, but for any number system.

More here.

Biden’s Child Tax Credit as Universal Basic Income

Robert Kuttner in American Prospect:

For several decades, child advocates have tried to bring more public indignation to the scandal of extreme child poverty, and have pushed for the expansion of the Child Tax Credit. In recent years, some progressives have called for something that seemed even more utopian, a universal basic income.

For several decades, child advocates have tried to bring more public indignation to the scandal of extreme child poverty, and have pushed for the expansion of the Child Tax Credit. In recent years, some progressives have called for something that seemed even more utopian, a universal basic income.

Well, gentle reader, we just got both. And the brilliance is in the details.

The credit, which is really a family allowance run through the IRS, provides $3,000 a year for each child under 18, topped up to $3,600 for kids under six. So a family with three kids gets almost $10,000. As a point of reference, the average income of the bottom 20 percent of American households is about $14,000.

The new Child Tax Credit will cut the rate of child poverty in half, and will raise the total incomes of the bottom fifth of American families by 33 percent. I never expected to see something like this in my lifetime.

More here.