Rachel Syme in The New Yorker:

About halfway through a recent episode of “POOG,” a new podcast that is essentially one long, unbroken conversation about “wellness” between the comedians and longtime friends Kate Berlant and Jacqueline Novak, the hosts spend several minutes trying—and failing—to devise a grand theory about the existential sorrow of eating ice cream. “The pleasure of eating an ice-cream cone for me,” Novak says, in the blustery tone of a motivational speaker, “involves the attempt to contain, catch up, stay present to the cone. Because the cone will not wait.” Berlant, a seasoned improviser, leaps into the game. “And it’s grief,” she says, with no trace of irony. “And it’s loss, because it’s so beautiful, it’s handed to you, and you’re constantly having to reckon with the fact that it is dying, and yet you’re experiencing it.”

About halfway through a recent episode of “POOG,” a new podcast that is essentially one long, unbroken conversation about “wellness” between the comedians and longtime friends Kate Berlant and Jacqueline Novak, the hosts spend several minutes trying—and failing—to devise a grand theory about the existential sorrow of eating ice cream. “The pleasure of eating an ice-cream cone for me,” Novak says, in the blustery tone of a motivational speaker, “involves the attempt to contain, catch up, stay present to the cone. Because the cone will not wait.” Berlant, a seasoned improviser, leaps into the game. “And it’s grief,” she says, with no trace of irony. “And it’s loss, because it’s so beautiful, it’s handed to you, and you’re constantly having to reckon with the fact that it is dying, and yet you’re experiencing it.”

From here, the conversation begins to warp into almost sublime absurdity. Novak suggests that what she ultimately desires is not the cone itself but the emptiness that comes after the cone has been consumed, or what she calls “the dead endlessness of infinite possibility.” She makes several attempts to refine this idea, in a state of increasing agitation. And then she begins to cry. “Are you crying because you are still untangling what this theory is?” Berlant asks. “No,” Novak blubbers. “I’m crying out of the humiliation of being seen as I am.”

At first, listening to this meltdown, I wondered what, precisely, was going on. Novak and Berlant are brilliant comics, denizens of the alternative-standup scene that bridges the gap between punch lines and performance art. They had to be up to something. And then, after several incantatory hours of listening to them talk, it became clear: “poog” is a show about wellness which is, in a dazzling and purposefully deranged way, utterly unwell. Of course Novak can’t process her desire to have everything and nothing at once; like so much of the language of being “healthy” in a fractured world, her yearning can never compute. “poog” is not just “Goop” (as in Gwyneth Paltrow’s life-style empire) spelled backward—it’s an attempt to push the wellness industrial complex fully through the looking glass. Each episode begins the same way. “This is our hobby,” Berlant says. “This is our hell,” Novak adds. “This is our naked desire for free products,” Berlant concludes.

More here.

What is the matrix? Without resorting to pharmaceuticals in various chromatic registers—red, blue—and the versions of paranoid reality such pills might produce, it feels right to recall the ways this concept has been deployed in mediums neither cinematic nor far-right political. In the early 1990s, Kevin Young wrote in an essay about the poet N.H. Pritchard, “The concept of the matrix is that the matrix is the concept, or rather, the paradigm from which the poem gets produced.” That is, the matrix is abstract structure that, as the French literary theorist Michael Riffaterre writes in Semiotics of Poetry (1978), “becomes visible only in its variants, the ungrammaticalities.” For James Edward Smethurst, the matrix is the Black Arts Matrix of the late 20th century, as tracked in “Foreground and Underground: the Left, Nationalism, and the Origins of the Black Arts Matrix,” the first chapter in his treatise The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s (2005).

What is the matrix? Without resorting to pharmaceuticals in various chromatic registers—red, blue—and the versions of paranoid reality such pills might produce, it feels right to recall the ways this concept has been deployed in mediums neither cinematic nor far-right political. In the early 1990s, Kevin Young wrote in an essay about the poet N.H. Pritchard, “The concept of the matrix is that the matrix is the concept, or rather, the paradigm from which the poem gets produced.” That is, the matrix is abstract structure that, as the French literary theorist Michael Riffaterre writes in Semiotics of Poetry (1978), “becomes visible only in its variants, the ungrammaticalities.” For James Edward Smethurst, the matrix is the Black Arts Matrix of the late 20th century, as tracked in “Foreground and Underground: the Left, Nationalism, and the Origins of the Black Arts Matrix,” the first chapter in his treatise The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s (2005).

What’s so fantastic about seeing these paintings at the Frick Breuer is not only how close you can get to the work, now that it’s not surrounded with furniture and bric-a-brac. In the mansion, the Fragonards are installed — even swaddled and segregated — in a wonderful Rococo drawing room, with attendant panels over doors and next to windows. Here, the work is given pride of place on the fourth floor next to the gigantic trapezoidal window looking out over Madison Avenue. Up close and at eye level, the work is reborn as these huge heraldic thunderous paintings, visually vehement and emotionally commanding. I love them more than I ever have.

What’s so fantastic about seeing these paintings at the Frick Breuer is not only how close you can get to the work, now that it’s not surrounded with furniture and bric-a-brac. In the mansion, the Fragonards are installed — even swaddled and segregated — in a wonderful Rococo drawing room, with attendant panels over doors and next to windows. Here, the work is given pride of place on the fourth floor next to the gigantic trapezoidal window looking out over Madison Avenue. Up close and at eye level, the work is reborn as these huge heraldic thunderous paintings, visually vehement and emotionally commanding. I love them more than I ever have. When the London-based neurologist Suzanne O’Sullivan flew to Sweden to visit a sick girl in a small town north-west of Stockholm, the child did not acknowledge her. Not when O’Sullivan entered her bedroom, or when she knelt down to introduce herself, or even when she examined her. Nola (not her real name) wasn’t trying to be rude. It had been more than a year since she had got out of bed, opened her eyes or moved at all. A feeding tube, taped to her cheek, kept her alive.

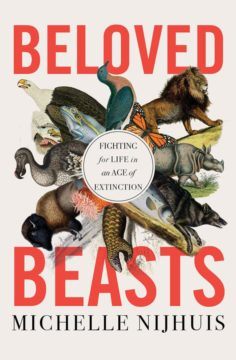

When the London-based neurologist Suzanne O’Sullivan flew to Sweden to visit a sick girl in a small town north-west of Stockholm, the child did not acknowledge her. Not when O’Sullivan entered her bedroom, or when she knelt down to introduce herself, or even when she examined her. Nola (not her real name) wasn’t trying to be rude. It had been more than a year since she had got out of bed, opened her eyes or moved at all. A feeding tube, taped to her cheek, kept her alive. Today’s conservationists

Today’s conservationists Rovelli has written a new book. Its title, Helgoland, refers to a barren island off the North Sea coast of Germany, where the 23-year-old physicist Werner Heisenberg (who would go on to work on the unrealised Nazi atomic bomb) retreated in June 1925. He was trying to make sense of recent atomic experiments, which had revealed an Alice in Wonderland submicroscopic realm where a single atom could be in two places at once; where events happened for no reason at all; and where atoms could influence each other instantaneously—even if on opposite sides of the universe.

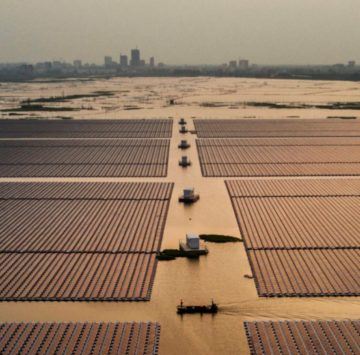

Rovelli has written a new book. Its title, Helgoland, refers to a barren island off the North Sea coast of Germany, where the 23-year-old physicist Werner Heisenberg (who would go on to work on the unrealised Nazi atomic bomb) retreated in June 1925. He was trying to make sense of recent atomic experiments, which had revealed an Alice in Wonderland submicroscopic realm where a single atom could be in two places at once; where events happened for no reason at all; and where atoms could influence each other instantaneously—even if on opposite sides of the universe. In the Himalayas and the Middle East, countries feud over water. In the African Sahel, farmers feud over cropland. In the melting Arctic, governments feud over seabed minerals. Climate change has provided bottomless inspiration for aspiring paperback novelists. But while thrillers must thrill and generals must fret, fears about the national security threats that climate change could present remain too vague to act on. The geopolitical reasons for a strong U.S. response to climate change lie not in what Americans might imagine about tomorrow’s world politics but in the global political relationships at stake today.

In the Himalayas and the Middle East, countries feud over water. In the African Sahel, farmers feud over cropland. In the melting Arctic, governments feud over seabed minerals. Climate change has provided bottomless inspiration for aspiring paperback novelists. But while thrillers must thrill and generals must fret, fears about the national security threats that climate change could present remain too vague to act on. The geopolitical reasons for a strong U.S. response to climate change lie not in what Americans might imagine about tomorrow’s world politics but in the global political relationships at stake today. Some proponents of an intelligence explosion argue that it’s possible to increase a system’s intelligence without fully understanding how the system works. They imply that intelligent systems, such as the human brain or an A.I. program, have one or more hidden “intelligence knobs,” and that we only need to be smart enough to find the knobs. I’m not sure that we currently have many good candidates for these knobs, so it’s hard to evaluate the reasonableness of this idea. Perhaps the most commonly suggested way to “turn up” artificial intelligence is to increase the speed of the hardware on which a program runs. Some have said that, once we create software that is as intelligent as a human being, running the software on a faster computer will effectively create superhuman intelligence. Would this lead to an intelligence explosion?

Some proponents of an intelligence explosion argue that it’s possible to increase a system’s intelligence without fully understanding how the system works. They imply that intelligent systems, such as the human brain or an A.I. program, have one or more hidden “intelligence knobs,” and that we only need to be smart enough to find the knobs. I’m not sure that we currently have many good candidates for these knobs, so it’s hard to evaluate the reasonableness of this idea. Perhaps the most commonly suggested way to “turn up” artificial intelligence is to increase the speed of the hardware on which a program runs. Some have said that, once we create software that is as intelligent as a human being, running the software on a faster computer will effectively create superhuman intelligence. Would this lead to an intelligence explosion? Morris’s writing took many forms. As well as maintaining a diary, he penned poems in multiple languages to the many women he seduced over the years in Europe and the United States (‘I know it to be wrong, but cannot help it’). He translated lines from Greek and Roman classics and produced pamphlets on finance and commerce. He also wrote the American constitution, quite literally. One of the fifty-odd delegates who met in Philadelphia over the summer of 1787 to draft this document, Morris chaired the constitutional convention’s ‘committee of style’ (the fact that a committee of this sort was judged desirable is suggestive). It was Morris, James Madison records, who was chiefly responsible for ‘the finish given to the style and arrangement’ of the American constitution. Most dramatically, it was he who replaced its initial matter-of-fact opening with one of the most influential phrases – and pieces of fiction – ever devised: ‘We the People of the United States…’

Morris’s writing took many forms. As well as maintaining a diary, he penned poems in multiple languages to the many women he seduced over the years in Europe and the United States (‘I know it to be wrong, but cannot help it’). He translated lines from Greek and Roman classics and produced pamphlets on finance and commerce. He also wrote the American constitution, quite literally. One of the fifty-odd delegates who met in Philadelphia over the summer of 1787 to draft this document, Morris chaired the constitutional convention’s ‘committee of style’ (the fact that a committee of this sort was judged desirable is suggestive). It was Morris, James Madison records, who was chiefly responsible for ‘the finish given to the style and arrangement’ of the American constitution. Most dramatically, it was he who replaced its initial matter-of-fact opening with one of the most influential phrases – and pieces of fiction – ever devised: ‘We the People of the United States…’ About halfway through a recent episode of “

About halfway through a recent episode of “ A lot of worry has been triggered by discoveries that variants of the pandemic-causing coronavirus

A lot of worry has been triggered by discoveries that variants of the pandemic-causing coronavirus  As we learn in The Tyranny of Merit, Michael Sandel’s view of meritocracy rests in part on the historical claim that it is grounded in the Calvinist understanding of predestination. “Combined with the idea that the elect must prove their election through work in a calling,” he writes, such a doctrine “leads to the notion that worldly success is a good indication of who is destined for salvation.” In this he follows Max Weber in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, but Sandel extends this thesis to the present moment, citing the evangelical idea of the “prosperity gospel” and the secular rationalizations of such well-known achievers as Lloyd Blankfein (CEO of Goldman Sachs) and John Mackey (founder of Whole Foods), who represent the understanding of health and wealth “as matters of praise and blame…a meritocratic way of looking at life.”

As we learn in The Tyranny of Merit, Michael Sandel’s view of meritocracy rests in part on the historical claim that it is grounded in the Calvinist understanding of predestination. “Combined with the idea that the elect must prove their election through work in a calling,” he writes, such a doctrine “leads to the notion that worldly success is a good indication of who is destined for salvation.” In this he follows Max Weber in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, but Sandel extends this thesis to the present moment, citing the evangelical idea of the “prosperity gospel” and the secular rationalizations of such well-known achievers as Lloyd Blankfein (CEO of Goldman Sachs) and John Mackey (founder of Whole Foods), who represent the understanding of health and wealth “as matters of praise and blame…a meritocratic way of looking at life.” “Time” and “the brain” are two of those things that are somewhat mysterious, but it would be hard for us to live without. So just imagine how much fun it is to bring them together. Dean Buonomano is one of the leading neuroscientists studying how our brains perceive time, which is part of the bigger issue of how we construct models of the physical world around us. We talk about how the brain tells time very differently than the clocks that we’re used to, using different neuronal mechanisms for different timescales. This brings us to a very interesting conversation about the nature of time itself — Dean is a presentist, who believes that only the current moment qualifies as “real,” but we don’t hold that against him.

“Time” and “the brain” are two of those things that are somewhat mysterious, but it would be hard for us to live without. So just imagine how much fun it is to bring them together. Dean Buonomano is one of the leading neuroscientists studying how our brains perceive time, which is part of the bigger issue of how we construct models of the physical world around us. We talk about how the brain tells time very differently than the clocks that we’re used to, using different neuronal mechanisms for different timescales. This brings us to a very interesting conversation about the nature of time itself — Dean is a presentist, who believes that only the current moment qualifies as “real,” but we don’t hold that against him. The hardest thing about teaching someone how to drive a boat is that it’s not at all like driving a car. To steer a car, you turn the wheel until your nose is pointing where you want to go, then you straighten out and go there. This works because the car is attached to the road. It’s when the car itself is no longer attached to the road that things get weird. When you turn too hard, for example, the rubber in your tyres loses purchase on the street, and you are “in drift”. The normal rules no longer apply.

The hardest thing about teaching someone how to drive a boat is that it’s not at all like driving a car. To steer a car, you turn the wheel until your nose is pointing where you want to go, then you straighten out and go there. This works because the car is attached to the road. It’s when the car itself is no longer attached to the road that things get weird. When you turn too hard, for example, the rubber in your tyres loses purchase on the street, and you are “in drift”. The normal rules no longer apply.