Lauren Michele Jackson in The New Yorker:

The story of Disney’s “The Lion King,” about a cub who avenges his uncle’s regicide, is said to have borrowed its bones from “Hamlet” (though Marlon James would say otherwise). “Black Is King,” the new “visual album” from Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter, borrows its bones from “The Lion King,” and is comparably interested in rehearsing the drama of its source material—which is to say, not very interested at all. The project is a cinematic adaptation of “The Lion King: The Gift,” the Beyoncé-produced companion album to Disney’s 2019 remake of the film, in which she voiced the part of Nala and for which she created an original song. “Black Is King” follows a young child (Folajomi Akinmurele) whose wayward adventures and visions provoke the question of what kind of man he will become. Royal titles are treated, with urgency, as a means of affirming the innate worth of the human spirit, a message that the film aims especially at the many Black peoples who were long denied the status of human (and, depending on who is asked, still are). Anchored by the lyrical grandeur of its soundtrack, which includes the fourteen songs co-written and co-produced by Beyoncé for “The Gift” (“black parade,” a bonus single on the deluxe edition of the soundtrack, plays during the credits),“Black Is King” expertly slides between talk of bloodlines and molded thrones and more modest—but far from modest—footage of impeccably styled, beautiful Black people in motion.

The story of Disney’s “The Lion King,” about a cub who avenges his uncle’s regicide, is said to have borrowed its bones from “Hamlet” (though Marlon James would say otherwise). “Black Is King,” the new “visual album” from Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter, borrows its bones from “The Lion King,” and is comparably interested in rehearsing the drama of its source material—which is to say, not very interested at all. The project is a cinematic adaptation of “The Lion King: The Gift,” the Beyoncé-produced companion album to Disney’s 2019 remake of the film, in which she voiced the part of Nala and for which she created an original song. “Black Is King” follows a young child (Folajomi Akinmurele) whose wayward adventures and visions provoke the question of what kind of man he will become. Royal titles are treated, with urgency, as a means of affirming the innate worth of the human spirit, a message that the film aims especially at the many Black peoples who were long denied the status of human (and, depending on who is asked, still are). Anchored by the lyrical grandeur of its soundtrack, which includes the fourteen songs co-written and co-produced by Beyoncé for “The Gift” (“black parade,” a bonus single on the deluxe edition of the soundtrack, plays during the credits),“Black Is King” expertly slides between talk of bloodlines and molded thrones and more modest—but far from modest—footage of impeccably styled, beautiful Black people in motion.

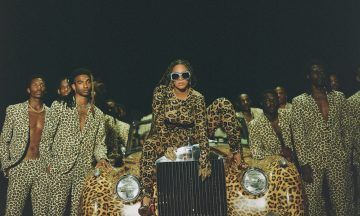

…The album’s knowingly ethnic splendor is mesmerizing in its scope; it does not attempt to provide cultural lessons but, rather, invitations to awesome delights. Above all, “Black Is King” is a tribute to the manifold ways that a body can be displayed, from root to toe, dressed up and painted in white, gold, seafoam, lilac, electric green, and pink; in cowhide, denim and tulle, ink, acrylic, lace, leopard, and satin, and fringe; cowry shells and goddess braids; bejewelled everything; good shirts tucked into good chinos; pearl-drenched headdresses, harnesses, thick gold rings; gowns and bleached tips, evening gloves, track jackets, catsuits, tunics, chunky sneakers, mammoth gele; cornrows, ribbon-wrapped feet, cargo pants, and trapezoidal shades. Also, the manifold ways in which a body can move: legwork, footwork, shaku shaku, zanku, twerk, wine, gbese, thrust, grind, shake—the grounded, weight-changing style of choreography that Beyoncé has been fond of since working with the Mozambican trio Tofo Tofo on “Run the World (Girls),” which is prominently shown here in her duet with the Afrobeats artist and divine dancer Stephen Ojo, in “already,” performed with Shatta Wale and Major Lazer. Though Beyoncé, when she appears onscreen, is usually at its center, “Black Is King” also cedes the floor to such charismatic movers as the Afropop artist Yemi Alade, who is featured on “don’t jealous me” and “my power,” alongside the South African artists Moonchild Sanelly and Busiswa and also a supreme slate of professional dancers. There is, in our present moment, a palpable, and reasonable, fatigue when it comes to the superlative showiness of a certain class of celebrity. Some of this sticks to Beyoncé, in particular, given the outsized scale at which she has been working for a while now. But this production—or, rather, the dozens of credited designers, stylists, artists, tailors, architects, weavers, seamstresses, builders, braiders, jewellers, and dancers whose crafts are on display in it—marvels in a way that is difficult to scoff at, especially given that we aren’t likely to see such feats again soon.

More here.