Eileen Myles in Bookforum:

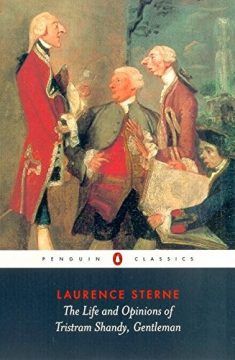

TRISTRAM SHANDY sailed into eighteenth-century literary history alongside such bawdy picaresques as Tom Jones. But unlike the rest Laurence Sterne’s creation is an antinovel: It starts and stops, has entire pages that aren’t even text—blank or solid black or marbled or filled with lines and swirls that indicate the wayward shapes of the narrative (at such moments it seems like what Sterne really is is a concrete poet). On the occasions when the author doesn’t want you to know what naughty thing he’s saying (though he quit being a minister to write, Sterne was still a modest man) there are heaving piles of asterisks. By such means—explained in an insanely arch but persistently conversational manner—you get that the book in your hands is alive and it will turn any whimsical damn way he wants. Laurence Sterne is a funny guy and there is a devastating presentness to this work.

TRISTRAM SHANDY sailed into eighteenth-century literary history alongside such bawdy picaresques as Tom Jones. But unlike the rest Laurence Sterne’s creation is an antinovel: It starts and stops, has entire pages that aren’t even text—blank or solid black or marbled or filled with lines and swirls that indicate the wayward shapes of the narrative (at such moments it seems like what Sterne really is is a concrete poet). On the occasions when the author doesn’t want you to know what naughty thing he’s saying (though he quit being a minister to write, Sterne was still a modest man) there are heaving piles of asterisks. By such means—explained in an insanely arch but persistently conversational manner—you get that the book in your hands is alive and it will turn any whimsical damn way he wants. Laurence Sterne is a funny guy and there is a devastating presentness to this work.

The list of Shandean admirers includes Karl Marx, Thomas Jefferson, James Joyce, Goethe, Virginia Woolf, and David Foster Wallace. All the fuss is because so early on in English literature there was this upstart minister laughing at the act of writing and metonymically he’s laughing at life itself. And it’s the heaven of this book for me on both counts.

Yet in the midst of Tristram Shandy’s wily form-defying nature—there’s still no agreement as to whether the book is a novel at all—there is this blatant subject matter that can be variously identified as castration anxiety, (wounded) masculinity, impotence, fear of female genitalia and power, and an anticipation of, or even the fact of, being cuckolded. And kind of not minding it. One critic pointed out that every male is impotent in Tristram Shandy, including the town bull who ends the story.

More here.