Suzanne Schneider in Late Light:

Suzanne Schneider in Late Light:

For a word so laden with meaning, promise is a remarkably slippery term to define. A promise is a guarantee of sorts, but also one that can be broken, as in the child’s frequent retort—“But you promised!”—when the hoped for proves untenable. In a different register, promise is also possibility, potential, a little ray of light in the dark surround. “That sounds promising,” as the expression goes. Far from being compatible, these two deployments of promise pull in contradictory directions, not just semantically, but ethically and politically as well. One denotes entitlement rooted in the past; the other gestures at a hope that resides in a future still undetermined. Can we retain the possibility of promise without regarding anything as promised?

The tension between these different iterations of promise looms large within Barack Obama’s best-selling presidential memoir, A Promised Land. This is not the forum to dwell at length on the book’s 900 pages or to revisit the momentous events that punctuated Obama’s tenure. My questions are of a somewhat different nature. What does it mean to call America a promised land or, alternately—in George Washington’s preferred formulation—a land of promise? What does recourse to this trope indicate about Obama’s much-touted idealism and optimism, and the ways in which contemporary liberals more broadly reconcile the undisputed horrors of the past with the prospect of a better future?

Beyond score settling and narrative making, the presidential memoir reads like an attempt to peddle a particular mode of optimism well beyond its sell-by date. No doubt critics who bill themselves realists will find much here that incriminates not merely the former president or liberalism as a political philosophy, but idealism in any form. Most major outlets have published reviews of A Promised Land, and many of them laud Obama for heroically maintaining his optimism even after gnashing his teeth against the cold, hard realities of “The World as It Is”—the title of part five of the book—daring to assert, four years after the election of Donald J. Trump to the nation’s highest office, that he still believes in “the idea of America.”

More here.

Eduardo Peñalver in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

Eduardo Peñalver in The Chronicle of Higher Education: Maggie Gyllenhaal has a theory that the mothers we see on-screen tend to fall into one of two categories. First, there’s the “fantasy mother,” who’s perfect in every way except when she has, say, some oatmeal on her sweater or runs a little late for a parent-teacher conference. On the flip side is the “monstrous mother,” who either mistreats her children or struggles with emotions that stifle her ability to parent; her story arc builds toward making her more palatable to viewers. Many films that attempt to rehabilitate an imperfect mother, such as Woman Under the Influence and Terms of Endearment, have been directed by great artists, and these characters have been played by great actors. And yet, Gyllenhaal told me over Zoom last month, with such movies, “you’re basically watching the destruction of this powerful life force.”

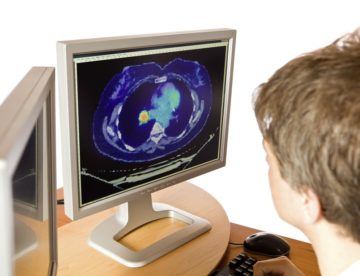

Maggie Gyllenhaal has a theory that the mothers we see on-screen tend to fall into one of two categories. First, there’s the “fantasy mother,” who’s perfect in every way except when she has, say, some oatmeal on her sweater or runs a little late for a parent-teacher conference. On the flip side is the “monstrous mother,” who either mistreats her children or struggles with emotions that stifle her ability to parent; her story arc builds toward making her more palatable to viewers. Many films that attempt to rehabilitate an imperfect mother, such as Woman Under the Influence and Terms of Endearment, have been directed by great artists, and these characters have been played by great actors. And yet, Gyllenhaal told me over Zoom last month, with such movies, “you’re basically watching the destruction of this powerful life force.” If a single medical objective could be applied to the entire range of cancers, it would be detecting the disease as soon as possible. “At the highest level, finding any cancer early gives you the opportunity for curative treatments,” says Andrea Ferris, CEO of research funding organization, LUNGevity.

If a single medical objective could be applied to the entire range of cancers, it would be detecting the disease as soon as possible. “At the highest level, finding any cancer early gives you the opportunity for curative treatments,” says Andrea Ferris, CEO of research funding organization, LUNGevity. I

I Even if Peter Bogdanovich, who died on Thursday, at the age of eighty-two, had never exposed a frame of film as a director, he’d be one of the history-making heroes of the world of movies.

Even if Peter Bogdanovich, who died on Thursday, at the age of eighty-two, had never exposed a frame of film as a director, he’d be one of the history-making heroes of the world of movies.  It was exactly two years ago that it first became publicly knowable—though most of us wouldn’t know for at least two more months—just how freakishly horrible is the branch of the wavefunction we’re on. I.e., that our branch wouldn’t just include Donald Trump as the US president, but simultaneously a global pandemic far worse than any in living memory, and a world-historically bungled response to that pandemic.

It was exactly two years ago that it first became publicly knowable—though most of us wouldn’t know for at least two more months—just how freakishly horrible is the branch of the wavefunction we’re on. I.e., that our branch wouldn’t just include Donald Trump as the US president, but simultaneously a global pandemic far worse than any in living memory, and a world-historically bungled response to that pandemic. Last June, we

Last June, we  More than 2,300 years ago, Aristotle wrote about eudaimonia—commonly translated as human flourishing—and discussed how we can best live our lives. It is a concept that has influenced philosophers through the ages, from Thomas Aquinas to Martha Nussbaum, who have in different ways developed theories about how we can live the good life and fulfil our true capability and potential as human beings.

More than 2,300 years ago, Aristotle wrote about eudaimonia—commonly translated as human flourishing—and discussed how we can best live our lives. It is a concept that has influenced philosophers through the ages, from Thomas Aquinas to Martha Nussbaum, who have in different ways developed theories about how we can live the good life and fulfil our true capability and potential as human beings. Barbara F. Walter, a political scientist at the University of California, San Diego, has interviewed many people who’ve lived through civil wars, and she told me they all say they didn’t see it coming. “They’re all surprised,” she said. “Even when, to somebody who studies it, it’s obvious years beforehand.”

Barbara F. Walter, a political scientist at the University of California, San Diego, has interviewed many people who’ve lived through civil wars, and she told me they all say they didn’t see it coming. “They’re all surprised,” she said. “Even when, to somebody who studies it, it’s obvious years beforehand.” I meet Bob Leverett in a small gravel parking lot at the end of a quiet residential road in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. We are at the Ice Glen trailhead, half a mile from a Mobil station, and Leverett, along with his wife, Monica Jakuc Leverett, is going to show me one of New England’s rare pockets of old-growth forest. For most of the 20th century, it was a matter of settled wisdom that the ancient forests of New England had long ago fallen to the ax and saw. How, after all, could such old trees have survived the settlers’ endless need for fuel to burn, fields to farm and timber to build with? Indeed, ramping up at the end of the 17th century, the colonial frontier subsisted on its logging operations stretching from Maine to the Carolinas. But the loggers and settlers missed a few spots over 300 years, which is why we’re at Ice Glen on this hot, humid August day.

I meet Bob Leverett in a small gravel parking lot at the end of a quiet residential road in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. We are at the Ice Glen trailhead, half a mile from a Mobil station, and Leverett, along with his wife, Monica Jakuc Leverett, is going to show me one of New England’s rare pockets of old-growth forest. For most of the 20th century, it was a matter of settled wisdom that the ancient forests of New England had long ago fallen to the ax and saw. How, after all, could such old trees have survived the settlers’ endless need for fuel to burn, fields to farm and timber to build with? Indeed, ramping up at the end of the 17th century, the colonial frontier subsisted on its logging operations stretching from Maine to the Carolinas. But the loggers and settlers missed a few spots over 300 years, which is why we’re at Ice Glen on this hot, humid August day. If

If  WRITER CHRIS KRAUS devotes a long section of her 1997 book I Love Dick to artist Hannah Wilke, who had passed away from lymphoma a few years earlier. Identifying with Wilke’s reputation as a “female monster,” Kraus glimpsed what few other writers at the time could see. Over a career spanning more than three decades, from the late 1950s until her last days in the cancer ward, where she died at age fifty-two, Wilke treated her art as a vector of her desire, “continuously exposing [herself] to whatever situation occurs,” as she put it in a 1976 statement. Rejected as a shameless exhibitionist, she carried on unhindered, refusing to place her sexuality—or her body—under wraps. Her striptease was relentless and ruthless, never more so than in her final body of work, “Intra-Venus,” 1992–93, a series of large-scale color photographs and videos in which the artist, sick with cancer, stunts for the camera in the costume of illness, still every bit the goddess in bandages and with an IV drip.

WRITER CHRIS KRAUS devotes a long section of her 1997 book I Love Dick to artist Hannah Wilke, who had passed away from lymphoma a few years earlier. Identifying with Wilke’s reputation as a “female monster,” Kraus glimpsed what few other writers at the time could see. Over a career spanning more than three decades, from the late 1950s until her last days in the cancer ward, where she died at age fifty-two, Wilke treated her art as a vector of her desire, “continuously exposing [herself] to whatever situation occurs,” as she put it in a 1976 statement. Rejected as a shameless exhibitionist, she carried on unhindered, refusing to place her sexuality—or her body—under wraps. Her striptease was relentless and ruthless, never more so than in her final body of work, “Intra-Venus,” 1992–93, a series of large-scale color photographs and videos in which the artist, sick with cancer, stunts for the camera in the costume of illness, still every bit the goddess in bandages and with an IV drip. The initiated had been familiar with the first edition for a long time, but with this new one, Bakhtin’s Dostoyevsky became a social phenomenon, a political symptom. At the center of this new furor was my friend and mentor, Tzvetan Stoyanov, well-known literary critic, anglophone, francophone, and obviously russophone. He had already introduced me to Shakespeare and Joyce, Cervantes and Kafka, the Russian formalists and the breakthrough postformalism of a certain Bakhtin. Now we could reimmerse ourselves, day and night, out loud and in Russian, Bakhtin’s book in hand, in the novels of Dostoyevsky. I heard the vocal power of tragic laughter, the farce within the force of evil, and that contagious, drunken flow of dialogues composed as story that Bakhtin calls slovo, translated as mot (word) in French. Through the vocabulary and syntax, I heard, as Logos incarnate, the Word stirring biblical deliverance into a new multivocal, multiversal narration…

The initiated had been familiar with the first edition for a long time, but with this new one, Bakhtin’s Dostoyevsky became a social phenomenon, a political symptom. At the center of this new furor was my friend and mentor, Tzvetan Stoyanov, well-known literary critic, anglophone, francophone, and obviously russophone. He had already introduced me to Shakespeare and Joyce, Cervantes and Kafka, the Russian formalists and the breakthrough postformalism of a certain Bakhtin. Now we could reimmerse ourselves, day and night, out loud and in Russian, Bakhtin’s book in hand, in the novels of Dostoyevsky. I heard the vocal power of tragic laughter, the farce within the force of evil, and that contagious, drunken flow of dialogues composed as story that Bakhtin calls slovo, translated as mot (word) in French. Through the vocabulary and syntax, I heard, as Logos incarnate, the Word stirring biblical deliverance into a new multivocal, multiversal narration…