Eric Dean Wilson in The Baffler:

Before arriving in Glasgow, the phrase I heard most in connection with the twenty-sixth Conference of the Parties for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP26) wasn’t “just transition” or “sustainability” or “resilience.” It wasn’t “carbon capture and storage” or “green hydrogen” or “renewable energy.” It was “shitshow.” Par exemple: “COP 26 is going to be a shitshow.”

Before arriving in Glasgow, the phrase I heard most in connection with the twenty-sixth Conference of the Parties for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP26) wasn’t “just transition” or “sustainability” or “resilience.” It wasn’t “carbon capture and storage” or “green hydrogen” or “renewable energy.” It was “shitshow.” Par exemple: “COP 26 is going to be a shitshow.”

I heard this from friends, activists, university colleagues. Everyone agreed that COP26 would be some kind of performance, the needle on the end of delusion. Greta Thunberg put it best in a speech she delivered one month before the conference at the Youth4Climate summit in Milan: “Green economy blah blah blah, net zero by 2050 blah blah blah . . . climate neutral blah blah blah . . . Our hopes and dreams drown in their empty words and promises.” Only nonsense named the truth of what would take place. Of what wouldn’t take place.

More here.

FLORENCE, Ariz.—Tonight, deep in the Arizona desert, thousands of people chanted for Donald Trump. They had braved the wind for hours—some waited the entire day—just to get a glimpse of the defeated former president. And when he finally appeared on stage, as Lee Greenwood played from the loudspeakers, the crowd roared as though Trump were still the commander-in-chief. To many of them, he is. “I ran twice and we won twice,” Trump told his fans. “This crowd is a massive symbol of what took place, because people are hungry for the truth. They want their country back.”

FLORENCE, Ariz.—Tonight, deep in the Arizona desert, thousands of people chanted for Donald Trump. They had braved the wind for hours—some waited the entire day—just to get a glimpse of the defeated former president. And when he finally appeared on stage, as Lee Greenwood played from the loudspeakers, the crowd roared as though Trump were still the commander-in-chief. To many of them, he is. “I ran twice and we won twice,” Trump told his fans. “This crowd is a massive symbol of what took place, because people are hungry for the truth. They want their country back.” On Wednesday, in the hours after Ronnie Spector’s family announced her passing from cancer at seventy-eight, I played, on loop, her cover of the Johnny Thunders punk anthem “You Can’t Put Your Arms Around a Memory.” Recorded for

On Wednesday, in the hours after Ronnie Spector’s family announced her passing from cancer at seventy-eight, I played, on loop, her cover of the Johnny Thunders punk anthem “You Can’t Put Your Arms Around a Memory.” Recorded for  I

I  “I

“I  One of the greatest physicists of the last century, Paul Dirac, had no use for emotions. “My life is mainly concerned with facts, not feelings,” he declared. He loved his emotion-free existence, or so it seemed, until he met a vivacious woman who was his exact opposite — impulsive and ardent. She became his wife and not only made him a happy man but also dramatically changed his personality. He became a feeling human being, which in turn affected his science. Yes, physics! If being logical and rational were all that mattered, we wouldn’t need actual physicists. The job could be done by computers. Later in life, Dirac became so convinced that knowledge needs to be combined with intuitions, crazy hunches and irrational perseverance that whenever he was asked about the secret to his success, he stressed that one needs to be guided above all by one’s emotions.

One of the greatest physicists of the last century, Paul Dirac, had no use for emotions. “My life is mainly concerned with facts, not feelings,” he declared. He loved his emotion-free existence, or so it seemed, until he met a vivacious woman who was his exact opposite — impulsive and ardent. She became his wife and not only made him a happy man but also dramatically changed his personality. He became a feeling human being, which in turn affected his science. Yes, physics! If being logical and rational were all that mattered, we wouldn’t need actual physicists. The job could be done by computers. Later in life, Dirac became so convinced that knowledge needs to be combined with intuitions, crazy hunches and irrational perseverance that whenever he was asked about the secret to his success, he stressed that one needs to be guided above all by one’s emotions. Zora Neale Hurston’s best-known sentence, judging by its appearance on coffee mugs and refrigerator magnets, is this one: “No, I do not weep at the world — I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife.”

Zora Neale Hurston’s best-known sentence, judging by its appearance on coffee mugs and refrigerator magnets, is this one: “No, I do not weep at the world — I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife.” A couple of months ago, when I gave a talk about my forthcoming book

A couple of months ago, when I gave a talk about my forthcoming book

Silicon Valley has no shortage of big ideas for transportation. In their vision of the future, we’ll hail driverless pods to go short distances – we may even be whisked into a network of underground tunnels that will supposedly get us to our destinations more quickly – and for intercity travel, we’ll switch to pods in vacuum tubes that will shoot us to our destination at 760 miles (1,220 km) per hour.

Silicon Valley has no shortage of big ideas for transportation. In their vision of the future, we’ll hail driverless pods to go short distances – we may even be whisked into a network of underground tunnels that will supposedly get us to our destinations more quickly – and for intercity travel, we’ll switch to pods in vacuum tubes that will shoot us to our destination at 760 miles (1,220 km) per hour. B

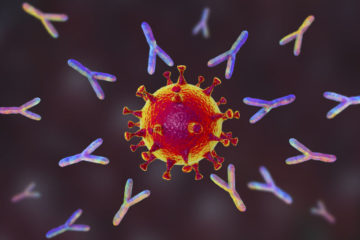

B Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis