Jack Miles at the LARB:

As an undergraduate, Francesca Stavrakopoulou observed to her theology professor that “lots of biblical texts suggest that God is masculine, with a male body,” and was told, to her evident frustration, that these texts were metaphorical, or poetic. “We shouldn’t get too distracted by references to his body,” her professor asserted, because to do so would be “to engage too simplistically with the biblical texts.” Anything but distracted by biblical references to God’s body, Stavrakopoulou is aesthetically entranced by them and programmatically attentive to their iconographic and literary contexts, from ancient Southwest Asia in the fourth millennium BCE to Christian and Jewish Europe as late as the 16th century. Her work, true to its subtitle, is anatomically organized into five parts plus an epilogue: I, “Feet and Legs”; II, “Genitals”; III, “Torso”; IV, “Arms and Hands”; V, “Head.” Each of these five major parts comprises three or four chapters, and each chapter has its own fresh emphasis and coherence. “Head,” for example, has separate chapters for ears, nose, and mouth.

As an undergraduate, Francesca Stavrakopoulou observed to her theology professor that “lots of biblical texts suggest that God is masculine, with a male body,” and was told, to her evident frustration, that these texts were metaphorical, or poetic. “We shouldn’t get too distracted by references to his body,” her professor asserted, because to do so would be “to engage too simplistically with the biblical texts.” Anything but distracted by biblical references to God’s body, Stavrakopoulou is aesthetically entranced by them and programmatically attentive to their iconographic and literary contexts, from ancient Southwest Asia in the fourth millennium BCE to Christian and Jewish Europe as late as the 16th century. Her work, true to its subtitle, is anatomically organized into five parts plus an epilogue: I, “Feet and Legs”; II, “Genitals”; III, “Torso”; IV, “Arms and Hands”; V, “Head.” Each of these five major parts comprises three or four chapters, and each chapter has its own fresh emphasis and coherence. “Head,” for example, has separate chapters for ears, nose, and mouth.

more here.

To think about the semantics of Smith’s work is above all to consider the labor that went into it, in the process informing how it was made. In this regard Smith’s story is well known. He famously welded steel, but also bent, pierced and cut it, lifted and placed it, often singlehandedly; in other words, he worked steel and iron directly, rather than turning to assistants to do the heavy lifting his art required.

To think about the semantics of Smith’s work is above all to consider the labor that went into it, in the process informing how it was made. In this regard Smith’s story is well known. He famously welded steel, but also bent, pierced and cut it, lifted and placed it, often singlehandedly; in other words, he worked steel and iron directly, rather than turning to assistants to do the heavy lifting his art required. Novak Djokovic, the world’s top-ranking tennis player, has just been granted a

Novak Djokovic, the world’s top-ranking tennis player, has just been granted a  The British lawyer is flush with energy, despite being at the tail end of a week-long visit with clients on the island nation of Mauritius. His casual black jacket, navy blue scarf, and black boots give him the appearance of a relaxed college professor. But his furrowed face and sharp gaze are those of a man who sees the world with a certain type of intensity.

The British lawyer is flush with energy, despite being at the tail end of a week-long visit with clients on the island nation of Mauritius. His casual black jacket, navy blue scarf, and black boots give him the appearance of a relaxed college professor. But his furrowed face and sharp gaze are those of a man who sees the world with a certain type of intensity.

DWINDLING ENLISTMENT AMONG STUDENTS and deteriorating market share among consumers; confusion as to immediate method and cloudiness as to ultimate mission. . . . Professors of literature have good reason to feel insecure about the status of literature and literary scholarship. And, like many an insecure person, the discipline of literary studies has grown increasingly interested in and respectful of popular taste as its own popularity has declined. Between the Great Recession and 2019, the number of undergrads majoring in English shrank by more than a quarter, and it’s difficult to imagine the pandemic has reversed the trend. Meanwhile, over approximately the same dozen years, professors in English and other literature departments have more and more bent their attention away from the real or alleged masterpieces that formed the staple of literature courses ever since the consolidation of English as a field of study in the 1930s, and toward more popular or ordinary fare. Sometimes the new objects of study are popular books in that they belong to previously overlooked or scorned genres of “popular fiction,” such as crime novels, sci-fi, or horror: this is popularity from the standpoint of consumption. And sometimes they are popular books in the different sense that they are written, in huge quantities, by authors with few if any readers, whatever the genre of their work: this is popularity from the standpoint of production.

DWINDLING ENLISTMENT AMONG STUDENTS and deteriorating market share among consumers; confusion as to immediate method and cloudiness as to ultimate mission. . . . Professors of literature have good reason to feel insecure about the status of literature and literary scholarship. And, like many an insecure person, the discipline of literary studies has grown increasingly interested in and respectful of popular taste as its own popularity has declined. Between the Great Recession and 2019, the number of undergrads majoring in English shrank by more than a quarter, and it’s difficult to imagine the pandemic has reversed the trend. Meanwhile, over approximately the same dozen years, professors in English and other literature departments have more and more bent their attention away from the real or alleged masterpieces that formed the staple of literature courses ever since the consolidation of English as a field of study in the 1930s, and toward more popular or ordinary fare. Sometimes the new objects of study are popular books in that they belong to previously overlooked or scorned genres of “popular fiction,” such as crime novels, sci-fi, or horror: this is popularity from the standpoint of consumption. And sometimes they are popular books in the different sense that they are written, in huge quantities, by authors with few if any readers, whatever the genre of their work: this is popularity from the standpoint of production. A few days after the Capitol insurrection last January, the FBI got two tips identifying an Ohio man named Walter Messer as a participant, and both cited his social media posts about being there. To verify those tips, the FBI turned to three companies that held a large amount of damning evidence against Messer, simply as a result of his normal use of their services: AT&T, Facebook, and Google. AT&T gave the FBI Messer’s telephone number and a list of cell sites he used, including one that covered the US Capitol building at the time of the insurrection, per the

A few days after the Capitol insurrection last January, the FBI got two tips identifying an Ohio man named Walter Messer as a participant, and both cited his social media posts about being there. To verify those tips, the FBI turned to three companies that held a large amount of damning evidence against Messer, simply as a result of his normal use of their services: AT&T, Facebook, and Google. AT&T gave the FBI Messer’s telephone number and a list of cell sites he used, including one that covered the US Capitol building at the time of the insurrection, per the  This is rich-kid-slacker fiction that takes no pains to present itself as anything but, measured out in doses of LSD and cannabis, a dithering New York-Taiwan loop, resigned to a weave of daily documentation and bite-sized odes to withdrawal. Part of the oddness of Leave Society’s spirit is not only how tepid its idea of departure is, but how redundant: The writer who makes so much of stepping out of the social circle, patly denouncing its bodily harms—society is a mess of toxins, radioactivity, and shaky healthcare—barely has a toehold in it to begin with. (Lin’s protagonist doing handstands in his midtown apartment to force himself to happy faintness is a less campy, but equally kooky echo of Huysmans’s reclusive snob-prince spraying a rainbow of perfumes in the air of his mansion and dashing through the vapors to reach solitary aesthetic nirvana.)

This is rich-kid-slacker fiction that takes no pains to present itself as anything but, measured out in doses of LSD and cannabis, a dithering New York-Taiwan loop, resigned to a weave of daily documentation and bite-sized odes to withdrawal. Part of the oddness of Leave Society’s spirit is not only how tepid its idea of departure is, but how redundant: The writer who makes so much of stepping out of the social circle, patly denouncing its bodily harms—society is a mess of toxins, radioactivity, and shaky healthcare—barely has a toehold in it to begin with. (Lin’s protagonist doing handstands in his midtown apartment to force himself to happy faintness is a less campy, but equally kooky echo of Huysmans’s reclusive snob-prince spraying a rainbow of perfumes in the air of his mansion and dashing through the vapors to reach solitary aesthetic nirvana.) For Weerasethakul, movies are the perfect medium through which to convey life’s continuums and interruptions. His mid-career masterpiece, “Tropical Malady” (2004), for instance, opens with soldiers in a field of tall grass, posing with a corpse. Posing and laughing: even in the presence of death, Weerasethakul seems to be saying, we pretend for the camera, for our friends, the better to feel included—but in what? The brutality of living? The action shifts to Keng (Banlop Lomnoi), a soldier in a rural community in northeastern Thailand. Keng meets Tong (Sakda Kaewbuadee), a sweet, younger man, a civilian, and the two begin a relationship against a backdrop of big Thai sky and dark, breathing jungle. Weerasethakul develops a new choreography for the dance of love, the malady of love. There are no sweeping violins or roiling surf. The depth of the men’s intimacy is shown in the way their knees play a game as they sit in a movie theatre, in the way they caress and lick each other’s hands.

For Weerasethakul, movies are the perfect medium through which to convey life’s continuums and interruptions. His mid-career masterpiece, “Tropical Malady” (2004), for instance, opens with soldiers in a field of tall grass, posing with a corpse. Posing and laughing: even in the presence of death, Weerasethakul seems to be saying, we pretend for the camera, for our friends, the better to feel included—but in what? The brutality of living? The action shifts to Keng (Banlop Lomnoi), a soldier in a rural community in northeastern Thailand. Keng meets Tong (Sakda Kaewbuadee), a sweet, younger man, a civilian, and the two begin a relationship against a backdrop of big Thai sky and dark, breathing jungle. Weerasethakul develops a new choreography for the dance of love, the malady of love. There are no sweeping violins or roiling surf. The depth of the men’s intimacy is shown in the way their knees play a game as they sit in a movie theatre, in the way they caress and lick each other’s hands. When I first learned of Ed’s death I felt a deep sense of personal loss given his extensive influence on my own life and academic career. As a Junior at Harvard I took Ed’s course in evolutionary biology. It was electrifying. In at least one of his lectures he talked about his repeated dreams of visiting oceanic islands and what exciting places for biological research they could be. His descriptions of his dreams, and the lectures he gave about such islands and their various exotic species, were beyond infectious. A crucial element in their magic was Ed’s captivating eloquence, a use of language that bordered on poetry.

When I first learned of Ed’s death I felt a deep sense of personal loss given his extensive influence on my own life and academic career. As a Junior at Harvard I took Ed’s course in evolutionary biology. It was electrifying. In at least one of his lectures he talked about his repeated dreams of visiting oceanic islands and what exciting places for biological research they could be. His descriptions of his dreams, and the lectures he gave about such islands and their various exotic species, were beyond infectious. A crucial element in their magic was Ed’s captivating eloquence, a use of language that bordered on poetry. It was impossible to tell through the Antonov’s dusty porthole, but below me the ground was breathing, or, rather, exhaling.

It was impossible to tell through the Antonov’s dusty porthole, but below me the ground was breathing, or, rather, exhaling. The United States faces a democratic crisis, as we have been told for several years now. But what exactly does this mean? On the anniversary of the January 6 attempted coup, the answer may seem obvious: the crisis is perhaps most dramatically seen in the transformation of the national Republican Party, which has abandoned a policy-making role for one that simply seeks power. To this end, it has become intent on exploiting vulnerable state-level institutions to suppress votes, gerrymander districts, and allow partisan actors to overturn the popular vote.

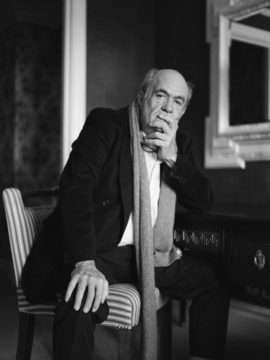

The United States faces a democratic crisis, as we have been told for several years now. But what exactly does this mean? On the anniversary of the January 6 attempted coup, the answer may seem obvious: the crisis is perhaps most dramatically seen in the transformation of the national Republican Party, which has abandoned a policy-making role for one that simply seeks power. To this end, it has become intent on exploiting vulnerable state-level institutions to suppress votes, gerrymander districts, and allow partisan actors to overturn the popular vote. In conversation, the Irish writer Colm Tóibín, the winner of the 2021 David Cohen Prize for Literature, employs a range of corroborating gestures. During moments of leisurely explanatory flow, he uses the back of his right hand to fondle the air just in front of him, or to fold it in gentle Nigella-ish revolutions. When he wants to achieve a tone of emphasis, a stab of the index finger accompanies every carefully chosen word. In more pensive moments, he likes to stroke his head, which is bald except for tufts around the back and side in the manner of his hero Henry James, the subject of his novel The Master (2004). On a recent afternoon, sitting in a library-like, though bookless, room in a small central London hotel, he preferred to lean forward from his armchair, arching his noble lined face towards the coffee table that lay between us – a disposition that reflected the infinite seriousness with which he takes “the creation of character and setting of scenes”.

In conversation, the Irish writer Colm Tóibín, the winner of the 2021 David Cohen Prize for Literature, employs a range of corroborating gestures. During moments of leisurely explanatory flow, he uses the back of his right hand to fondle the air just in front of him, or to fold it in gentle Nigella-ish revolutions. When he wants to achieve a tone of emphasis, a stab of the index finger accompanies every carefully chosen word. In more pensive moments, he likes to stroke his head, which is bald except for tufts around the back and side in the manner of his hero Henry James, the subject of his novel The Master (2004). On a recent afternoon, sitting in a library-like, though bookless, room in a small central London hotel, he preferred to lean forward from his armchair, arching his noble lined face towards the coffee table that lay between us – a disposition that reflected the infinite seriousness with which he takes “the creation of character and setting of scenes”.