Category: Recommended Reading

Saturday, January 1, 2021

Why Academic Freedom Matters

Nishi Shah in The Raven:

Nishi Shah in The Raven:

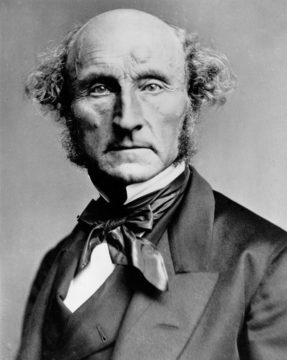

In the midst of the 2020 protests for racial justice, I prepared to teach my annual July mini-course on free speech for incoming FLI (First-Generation and/or Low-Income) students at Amherst College. Almost all of these students are persons of color. My aim in this course is to show students how to analyze the reasoning in an important but difficult text from the history of philosophy, something for which most high schoolers have little training. The text I chose was John Stuart Mill’s famous defense of free speech in On Liberty. But I like to begin the course with a discussion of a specific free-speech controversy, so that, after reading On Liberty, students can reflect on whether this 19th century essay by a dead white male has something enlightening to say to us. Last summer, my idea was to have that initial discussion about Senator Tom Cotton’s recently published op-ed in the New York Times defending the federal government’s military response to the Black Lives Matter protests in Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C. After receiving heavy criticism from readers, the Times conducted a review, concluded that it should not have published the essay, issued a public apology, and eventually forced the resignation of James Bennet, the editor of the opinion page. Two Times opinion writers, Ross Douthat and Michelle Goldberg, wrote subsequent essays in the Times, one in favor (Goldberg) and one against (Douthat) these decisions. For the first day of class, I asked my students to read both essays along with the original Cotton op-ed, and write on the following question: Do you think the New York Times should have published Cotton’s essay? Why or why not?

More here.

On Language Games

Jon Baskin in The Point:

Jon Baskin in The Point:

For a country so often believed to be anti-intellectual, it is striking how much of American political conversation has come to revolve around seemingly pedantic quarrels about terminology. Critical race theory, which dominated media analysis of the Virginia governor’s race this November, might have been a new term to many who tuned into the political news in the days following the election, but the shape of the argument about its meaning and function was so familiar that it is hard not to reach for a psychoanalytic vocabulary when describing it. The neurotic process commences when a term or theory that had started life decades ago at some obscure intersection between academia and left-wing activism—before CRT, there was political correctness, intersectionality and identity politics—begins to be publicized by progressive activists and commentators as a superior way to talk about some broader set of social phenomena. Taking advantage of its newly expanded—and usually piecemeal—application, right-wing critics then respond by seizing on the term as a blanket pejorative for an approach to social problems they oppose, while simultaneously connecting it to various other charter members of their lexicon of Bad Things (like Nazism and… Kant?). At this point, progressive intellectuals accuse conservative columnists of peddling “absolute nonsense” while at the same time deriding ordinary people who begin to apply the term for being either dupes (for falling for a “moral panic”) or bigots (for using the term to soft-pedal their own prejudice). Both progressive accusations imply that the people who use the new terms inappropriately are, at the very least, hopelessly confused about the meaning of their own words, which in turn allows right-wing critics to reprise the familiar accusation that progressives are always lecturing people about what to call things. Now the process has reached its terminal phase: the concept is too ideologically freighted to serve as anything other than an occasion for meta-discussions about the debate itself (like this one), which means we are close to the end of one cycle—and the beginning of its compulsive repetition.

More here.

A Philosopher in Hard Times

Michael S. Roth in The LA Review of Books:

Michael S. Roth in The LA Review of Books:

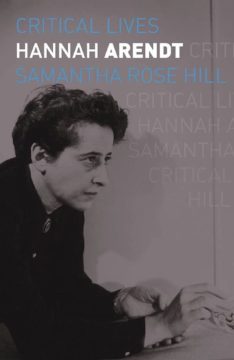

SAMANTHA ROSE HILL’s intellectual biography of Hannah Arendt is a timely look at one of the most impactful, if elusive, 20th-century political thinkers. The book makes accessible key themes in Arendt’s work. Looking for a philosophical focus on creative work that escapes the mystical Teutonic fog of Heidegger? See the concept of natality described in The Human Condition. Concerned about the rise of populist authoritarianism? The Origins of Totalitarianism remains a bracing read, its conceptual flaws and political agenda less important today than its description of the aspiration to tyrannical control. Want to step back from political relevance to something more primary? Arendt’s late reflections on thinking and judgment will be powerful. In all these cases, and many more, Hill is a thoughtful guide.

The early biography is covered quickly. Hill doesn’t say much about the impact of the death of Hannah’s father, only noting with awkward foreshadowing that the loss did not diminish her “inherent wonder at being in the world.” Be that as it may, we know from Elisabeth Young-Bruehl’s more detailed 1982 biography that the seven-year-old Hannah maintained an unusually sunny disposition for months after her father’s death but a year later began acting out and succumbing to various ailments; Young-Bruehl understood this as Hannah’s way of grieving. The young girl’s family was unobservant, but she learned about her Jewish identity from the everyday antisemitism of the street. After her mother moved to East Prussia, a challenging place to be at the outbreak of World War I, Hannah took comfort in her books. Years later when asked by Günter Gaus why she had read Kant at such a young age, she responded, “I can either study philosophy or I can drown myself, so to speak.”

More here.

Saturday Poem

After the gentle Poet Kobayashi Issa

New Year’s morning—

everything is in blossom!

I feel about average.

A huge frog and I

staring at each other,

neither of us moves.

This moth saw brightness

in a woman’s chamber—

burned to a crisp.

Asked how old he was

the boy in the new kimono

stretched out all five fingers.

Blossoms at night,

like people

moved by music

Napped half the day;

no one

punished me!

Fiftieth birthday

From now on,

It’s all clear profit,

every sky.

Don’t worry, spiders,

I keep house

casually.

These sea slugs,

they just don’t seem

Japanese.

Hell:

Bright autumn moon;

pond snails crying

in the saucepan.

by Robert Hass

from Field Guide

Yale University Press

Happy New Year

The Editorial Board in Bangor Daily News:

Once again, just like clockwork, here comes New Year’s Day. Once again, in a wave sweeping across time zones, the world counts backward from 10. Revelry and other traditions have been pared back this year as the coronavirus pandemic drags into yet another new year. The uncertain — but hopefully better — future will be welcomed in with a mixture of hope and trepidation. It’s an odd holiday. Jan. 1 is no great landmark in the course of human events; it is the anniversary of no remarkable birth, death or battle. The cosmos is not arranged in any particularly auspicious way. It is a date pulled out of a hat, an utterly arbitrary starting line for an eternal, repetitive relay race. The innocent baby takes the baton, sprints out with promise and hope, inevitably to stagger home a shattered old man, beaten down by 365 days of calamity, cruelty and chaos, especially so this year. And another baby invariably waits its turn.

Once again, just like clockwork, here comes New Year’s Day. Once again, in a wave sweeping across time zones, the world counts backward from 10. Revelry and other traditions have been pared back this year as the coronavirus pandemic drags into yet another new year. The uncertain — but hopefully better — future will be welcomed in with a mixture of hope and trepidation. It’s an odd holiday. Jan. 1 is no great landmark in the course of human events; it is the anniversary of no remarkable birth, death or battle. The cosmos is not arranged in any particularly auspicious way. It is a date pulled out of a hat, an utterly arbitrary starting line for an eternal, repetitive relay race. The innocent baby takes the baton, sprints out with promise and hope, inevitably to stagger home a shattered old man, beaten down by 365 days of calamity, cruelty and chaos, especially so this year. And another baby invariably waits its turn.

As a matter of history, humankind has always had a tough time with the new year. Oh, the ancient Chinese, Hindu and Mayan mathematicians, working back when math was fun and easy, had Earth’s trip around the sun down cold, figured out to the hundredth of a second. Then they would blow it by trying to schedule their version of the Rose Bowl on the anniversary of the creation of the universe — millennia before the invention of the three-day weekend, no less.

…Mark Twain, who said just about everything he said better than anyone else, put it this way: “Now is the accepted time to make your annual good resolutions. Next week you can begin paving hell with them. Yesterday, everybody smoked his last cigar, took his last drink and swore his last oath. Today, we are a pious and exemplary community. Thirty days from now, we shall have cast our reformation to the winds and go on cutting our ancient shortcomings shorter than ever.”

More here.

The Novelist Who Saw Middle America as It Really Was

Robert Gottlieb in The New York Times:

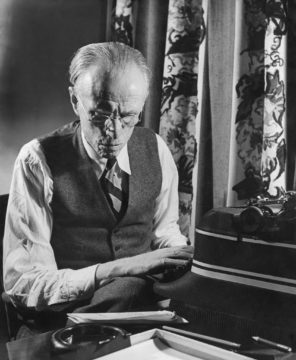

This is the centenary year of “Babbitt,” Sinclair Lewis’s best — and most misunderstood — novel. He had written five inconsequential books that had received respectable if not excited attention. And in 1920 — at the age of 35 — he had written “Main Street,” the most sensationally successful novel of the century to date: hundreds of thousands of copies sold, and a title that came to stand for the values, both narrow-minded and wholesome, of what we now call Middle America.

This is the centenary year of “Babbitt,” Sinclair Lewis’s best — and most misunderstood — novel. He had written five inconsequential books that had received respectable if not excited attention. And in 1920 — at the age of 35 — he had written “Main Street,” the most sensationally successful novel of the century to date: hundreds of thousands of copies sold, and a title that came to stand for the values, both narrow-minded and wholesome, of what we now call Middle America.

The Pulitzer Prize jury chose it as the year’s best novel, but in a scandalous reversal of their decision, the prize’s trustees refused to approve the award and presented it instead to Edith Wharton’s “The Age of Innocence.” A few years later, when the judges chose Lewis’s “Arrowsmith,” he refused to accept the prize — Sinclair Lewis had a thin skin. (Nothing ever changes: When in 1974 the jury unanimously chose Thomas Pynchon’s “Gravity’s Rainbow,” the prize’s overseers again refused to certify the decision, using words like “turgid” and “obscene” to justify their action.)

At the time of their publication, both “Main Street” and “Babbitt” were generally thought of as satirical novels, America being the object of the satire. Both “Main Street”’s Gopher Prairie, the small town that is the stand-in for Sauk Centre, Minn., where Lewis grew up, and Zenith, the medium-size city where Babbitt conducts his prosperous realty business, are meticulously and convincingly anatomized: Lewis always got the details right.

More here.

Friday, December 31, 2021

A new book ventures to the farthest reaches of the Marvel Universe and returns with stories to spare

Daniel Felsenthal in The Village Voice:

In a utopia, there’d be an issue for everyone. For me, it was Uncanny X-Men No. 414, which I read on the floor of a Pine Sol–scented Barnes and Noble when I was 11. Seated pretzel-legged in one of the aisles, I found something unexpectedly weighty in the Marvel comic: Abused by his father, a boy literally explodes. A lapsed superhero named Northstar discovers him in his home’s rubble. Northstar is gay, we know, because Professor Xavier, founder of a school for “gifted youngsters” with mutant powers they need to learn how to control, wants to hire the flying, ultrafast Canadian; he’d like to diversify his teaching staff so that his students have homosexual role models.

In a utopia, there’d be an issue for everyone. For me, it was Uncanny X-Men No. 414, which I read on the floor of a Pine Sol–scented Barnes and Noble when I was 11. Seated pretzel-legged in one of the aisles, I found something unexpectedly weighty in the Marvel comic: Abused by his father, a boy literally explodes. A lapsed superhero named Northstar discovers him in his home’s rubble. Northstar is gay, we know, because Professor Xavier, founder of a school for “gifted youngsters” with mutant powers they need to learn how to control, wants to hire the flying, ultrafast Canadian; he’d like to diversify his teaching staff so that his students have homosexual role models.

“Huh?” I thought, dropped from the drab retailer into a friendlier dimension. I’d never read anything so frankly queer before. The year was 2002, and I only knew gayness as the butt of jokes. Studio films were smattered with swishy stereotypes for comic relief, while the lyrics of Top 40 hitmakers like Eminem and DMX made mincemeat of homosexuals.

More here.

What Hot Dogs Can Teach Us About Number Theory

Patrick Honner in Quanta:

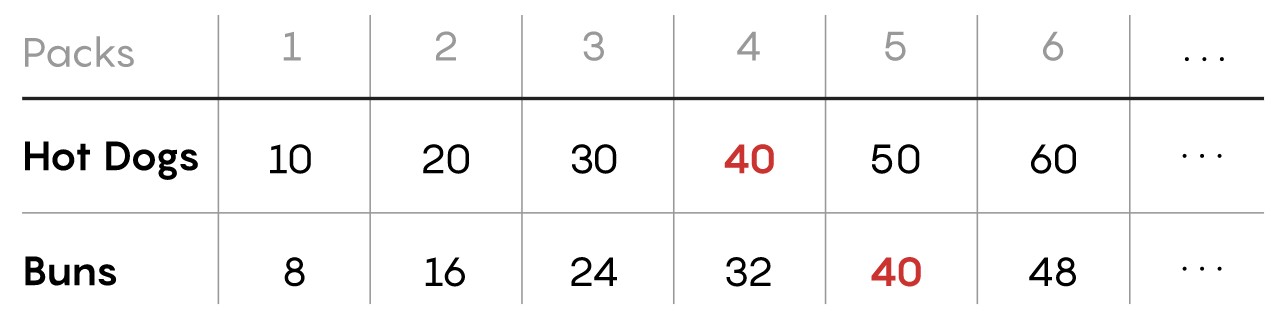

If you’ve ever had to buy hot dogs for a cookout, you might have found yourself solving a math problem involving least common multiples. Setting aside the age-old question of why hot dogs usually come in packs of 10 while buns come in packs of eight (you can read what the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council has to say about it here), let’s stick to the math that gets our hot dogs to match our buns. A simple solution is to buy eight packs of hot dogs and 10 packs of buns, but who needs 80 hot dogs? Can you buy fewer packs and still make the numbers match?

If you’ve ever had to buy hot dogs for a cookout, you might have found yourself solving a math problem involving least common multiples. Setting aside the age-old question of why hot dogs usually come in packs of 10 while buns come in packs of eight (you can read what the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council has to say about it here), let’s stick to the math that gets our hot dogs to match our buns. A simple solution is to buy eight packs of hot dogs and 10 packs of buns, but who needs 80 hot dogs? Can you buy fewer packs and still make the numbers match?

Let’s list how many of each item you get by purchasing multiple packs.

There’s a 40 on each list because 40 is the least common multiple (LCM) of 10 and 8 — it’s the smallest number that is evenly divisible by both numbers. If you buy four packs of hot dogs and five packs of buns, the 40 hot dogs will match up perfectly with the 40 buns.

But what if the hot dogs instead came in packs of five (maybe your friends and family like an artisanal brand that comes in prime-numbered packs), and even 40 is more than you need? Can you do better than the simple solution of buying eight packs of hot dogs and five packs of buns?

More here.

Deaths of despair: the unrecognized tragedy of working class immiseration

David Introcaso in Stat News:

The term deaths of despair comes from Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton, who set out to understand what accounted for falling U.S. life expectancies. They learned that the fastest rising death rates among Americans were from drug overdoses, suicide, and alcoholic liver disease. Deaths from these causes have increased between 56% and 387%, depending on the age cohort, over the past two decades, averaging 70,000 per year.

The term deaths of despair comes from Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton, who set out to understand what accounted for falling U.S. life expectancies. They learned that the fastest rising death rates among Americans were from drug overdoses, suicide, and alcoholic liver disease. Deaths from these causes have increased between 56% and 387%, depending on the age cohort, over the past two decades, averaging 70,000 per year.

Case and Deaton learned that these deaths disproportionately occurred in white men who had not earned college degrees. In their 2020 book, “Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism,” they argued that a key driver of these deaths is economic misery.

More here.

Karl Friston on Embodied Cognition

Mir Imran of Rani Therapeutics: I Am Living Proof Of The American Dream

Chef Vicky Colas in Authority Magazine:

Is the American Dream still alive? If you speak to many of the immigrants we spoke to, who came to this country with nothing but grit, resilience, and a dream, they will tell you that it certainly is still alive. As a part of our series about immigrant success stories, I had the pleasure of interviewing Mir Imran.

Is the American Dream still alive? If you speak to many of the immigrants we spoke to, who came to this country with nothing but grit, resilience, and a dream, they will tell you that it certainly is still alive. As a part of our series about immigrant success stories, I had the pleasure of interviewing Mir Imran.

Mir Imran has a unique background in medicine and engineering, which became the foundation of his work in innovation and company building. After attending medical school, Mir began his career as a healthcare entrepreneur in the late 1970’s and has founded more than 20 life sciences companies since those early days, more than half of which have been acquired. Mir holds more than 400 issued and pending patents and is perhaps most well-known for his pioneering contributions to the first FDA-approved Automatic Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD).

Thank you so much for joining us in this interview series! Can you tell us the story of how you grew up?

I was born in Hyderabad, India, a city right in the center of India. My father was a physician, my mother was a writer. We grew up with my grandmother taking care of us; my father practiced medicine in a small town a couple hundred miles away, so we only used to see my father every summer. It was a really wonderful environment growing up with the family, aunts and uncles and so on. I was a tinkerer from childhood, and I developed a deep interest in engineering — for science, physics and chemistry. My mother encouraged me a lot. In fact, I attribute the fostering of my curiosity to her — when I was a young boy, I liked to take toys apart to figure out how they worked. Instead of scolding me, she bought me two toys … one to play with and one to take apart. That was the beginning of my career in engineering.

More here.

Ketamine Therapy Is Going Mainstream. Are We Ready?

Emily Witt in The New Yorker:

In the fall of 1972, a psychiatrist named Salvador Roquet travelled from his home in Mexico City to the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, an institution largely funded by the United States government, to give a presentation on an ongoing experiment. For several years, Roquet had been running a series of group-therapy sessions: over the course of eight or nine hours, his staff would administer psilocybin mushrooms, morning-glory seeds, peyote cacti, and the herb datura to small groups of patients. He would then orchestrate what he called a “sensory overload show,” with lights, sounds, and images from violent or erotic movies. The idea was to push the patients through an extreme experience to a psycho-spiritual rebirth. One of the participants, an American psychology professor, described the session as a “descent into hell.” But Roquet wanted to give his patients smooth landings, and so, eventually, he added a common hospital anesthetic called ketamine hydrochloride. He found that, given as the other drugs were wearing off, it alleviated the anxiety brought on by these punishing ordeals.

In the fall of 1972, a psychiatrist named Salvador Roquet travelled from his home in Mexico City to the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, an institution largely funded by the United States government, to give a presentation on an ongoing experiment. For several years, Roquet had been running a series of group-therapy sessions: over the course of eight or nine hours, his staff would administer psilocybin mushrooms, morning-glory seeds, peyote cacti, and the herb datura to small groups of patients. He would then orchestrate what he called a “sensory overload show,” with lights, sounds, and images from violent or erotic movies. The idea was to push the patients through an extreme experience to a psycho-spiritual rebirth. One of the participants, an American psychology professor, described the session as a “descent into hell.” But Roquet wanted to give his patients smooth landings, and so, eventually, he added a common hospital anesthetic called ketamine hydrochloride. He found that, given as the other drugs were wearing off, it alleviated the anxiety brought on by these punishing ordeals.

Clinicians at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center had been studying LSD and other psychedelics since the early nineteen-fifties, beginning at a related institution, the Spring Grove Hospital Center. But ketamine was new: it was first synthesized in 1962, by a researcher named Calvin Stevens, who did consulting work for the pharmaceutical company Parke-Davis. (Stevens had been looking for a less volatile alternative to phencyclidine, better known as PCP.) Two years later, a doctor named Edward Domino conducted the first human trials of ketamine, with men incarcerated at Jackson State Prison, in Michigan, serving as his subjects. At higher doses, Domino noticed, ketamine knocked people out, but at lower ones it produced odd psychoactive effects on otherwise lucid patients. Parke-Davis wanted to avoid characterizing the drug as psychedelic, and Domino’s wife suggested the term “dissociative anesthetic” to describe the way it seemed to separate the mind from the body even as the mind retained consciousness. The F.D.A. approved ketamine as an anesthetic in 1970, and Parke-Davis began marketing it under the brand name Ketalar. It was widely used by the U.S. military during the Vietnam War, and remains a standard anesthetic in emergency rooms around the world.

Roquet found other uses for it. After his lecture in Maryland, he offered experiential training to the clinicians there. “I was introduced to the strangest psychoactive substance I have ever experienced in the 50 years of my consciousness research,” the psychiatrist Stanislav Grof recalls in “The Ketamine Papers,” a book edited by the psychiatrist Phil Wolfson and the researcher Glenn Hartelius.

More here. (Note: Thanks to Syed Tasnim Raza)

Friday Poem

All years come to an end. What then? —Toshi Suzuki

Since Anchoring to the San Francisco Dock, 1945

Before lifted

onto a gurney,

folded into plastic,

& zipped in a bag,

my grandpa says

his goodbyes

in Tagalog

8,000 miles

from where his brother

is a banana leaf

or sampaguita

or whatever

he became

of earth after

the imperial army

invaded.

by Troy Osaki

from Pank Magazine

Nobel Laureate Abdulrazak Gurnah And Zanzibar

Sameer Rahim at Prospect Magazine:

When Abdulrazak Gurnah was growing up in the 1950s in Zanzibar, a small island off the east African coast, he could not imagine a career as a writer. Though there were poets and storytellers, there were no literary publishers. At school he was taught the English canon. “You realise, in that literature, you’re completely and totally absent,” he tells me, “or present in some kind of diminished form.” But after moving to Britain in 1968, he did become a writer and, across 10 novels, has drawn on his island’s rich history to fill in those absences. In October, this quietly spoken man—always respected but hardly a household name—won the Nobel Prize in literature.

When Abdulrazak Gurnah was growing up in the 1950s in Zanzibar, a small island off the east African coast, he could not imagine a career as a writer. Though there were poets and storytellers, there were no literary publishers. At school he was taught the English canon. “You realise, in that literature, you’re completely and totally absent,” he tells me, “or present in some kind of diminished form.” But after moving to Britain in 1968, he did become a writer and, across 10 novels, has drawn on his island’s rich history to fill in those absences. In October, this quietly spoken man—always respected but hardly a household name—won the Nobel Prize in literature.

The decision delighted me, but I must admit a bias. My father also grew up in Zanzibar in the 1950s and I have read Gurnah’s work as much to learn about my family history as for its literary merit.

more here.

Interview With Abdulrazak Gurnah

The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe

Stathis N Kalyvas at Literary Review:

The year 2021 was meant to be special for Greece: an opportunity to celebrate the bicentenary of the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in 1821, which led to the birth of modern Greece. It was also supposed to be an occasion to mark the country’s slow and painful, yet also real and tangible, emergence from a vicious and protracted economic crisis that had brought it to its knees. The festivities were to be orchestrated by Gianna Angelopoulos-Daskalaki, the woman who single-handedly brought the Olympic Games to Athens in 2004 and ran them successfully, to general acclaim. Alas, it was not to be. The coronavirus thwarted Greece’s grand plans.

The year 2021 was meant to be special for Greece: an opportunity to celebrate the bicentenary of the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in 1821, which led to the birth of modern Greece. It was also supposed to be an occasion to mark the country’s slow and painful, yet also real and tangible, emergence from a vicious and protracted economic crisis that had brought it to its knees. The festivities were to be orchestrated by Gianna Angelopoulos-Daskalaki, the woman who single-handedly brought the Olympic Games to Athens in 2004 and ran them successfully, to general acclaim. Alas, it was not to be. The coronavirus thwarted Greece’s grand plans.

This unfortunate intervention might have been a blessing in disguise – and not because national celebrations belong to the past. As long as nation-states continue to exist, they will naturally want to commemorate these milestones.

more here.

Thursday, December 30, 2021

Why does a sport like boxing still exist?

Gordon Marino in The Common Reader:

On Saturday, September 11, Evander Holyfield, who turned 59 in October, was knocked out in the first round by the 44-year old former UFC champion, Vitor Belfort, in a commission sanctioned bout in Florida.

On Saturday, September 11, Evander Holyfield, who turned 59 in October, was knocked out in the first round by the 44-year old former UFC champion, Vitor Belfort, in a commission sanctioned bout in Florida.

If the promoters or the people who lined their pockets working this event or, for that matter, the viewers who shelled out fifty dollars to watch the degrading spectacle, had read Tris Dixon’s Damage, maybe they would have passed on this so-called fight. Then again, I doubt it.

For all the hand-wringing about chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in the NFL, there has been scant media mention or public concern about brain trauma in boxing. And yet, as one of Dixon’s interviewees framed it, “Boxing is American football head injuries on steroids.”

More here.

Observing Evolution: Peppered Moths And The Discovery Of Parallel Melanism

Leon Vlieger in The Inquisitive Biologist:

Every student of evolution will be familiar with the peppered moth, Biston betularia. It is right up there with the Galápagos finches as an example of evolution happening right under our noses. The story of the rapid spread of dark moths in response to the soot deposition that accompanied the Industrial Revolution, and the reversal of this pattern when air pollution abated, is iconic. Yet, as Emeritus Professor of biology Bruce S. Grant shows, there are a lot more subtleties to it than my one-liner suggests. Observing Evolution details research by himself and many others, and along the way addresses criticism – legitimate and otherwise – levelled at some of the earlier research. Eminently readable, this is a personal story of the rise, fall, and ultimate redemption of one of the most famous textbook examples of evolution in action.

Every student of evolution will be familiar with the peppered moth, Biston betularia. It is right up there with the Galápagos finches as an example of evolution happening right under our noses. The story of the rapid spread of dark moths in response to the soot deposition that accompanied the Industrial Revolution, and the reversal of this pattern when air pollution abated, is iconic. Yet, as Emeritus Professor of biology Bruce S. Grant shows, there are a lot more subtleties to it than my one-liner suggests. Observing Evolution details research by himself and many others, and along the way addresses criticism – legitimate and otherwise – levelled at some of the earlier research. Eminently readable, this is a personal story of the rise, fall, and ultimate redemption of one of the most famous textbook examples of evolution in action.

More here.

Public Choice Theory and the Illusion of Grand Strategy

Richard Hanania in his Substack newsletter:

Ever since I started studying IR, I had a gnawing feeling that something about the whole enterprise was off. As I read more history, and also in other fields like economics, anthropology and psychology, I came to the conclusion that the ways in which we talk about international relations and foreign policy are simply wrong. The whole reason that IR is its own subfield in political science is because of the “unitary actor model,” or the assumption that you can talk about a nation like you talk about an individual, with motivations, goals, and strategies. No one believes this in a literal sense, but it’s considered “close enough” for the sake of trying to understand the world. And although many IR scholars do look at things like psychology and state-specific factors to explain foreign policy, they generally don’t take the critique of the unitary actor model far enough. The more I studied the specifics of American foreign policy the more it looked irrational on a system-wide level and unconnected to any reasonable goals, which further made me skeptical of the assumptions of the field.

Ever since I started studying IR, I had a gnawing feeling that something about the whole enterprise was off. As I read more history, and also in other fields like economics, anthropology and psychology, I came to the conclusion that the ways in which we talk about international relations and foreign policy are simply wrong. The whole reason that IR is its own subfield in political science is because of the “unitary actor model,” or the assumption that you can talk about a nation like you talk about an individual, with motivations, goals, and strategies. No one believes this in a literal sense, but it’s considered “close enough” for the sake of trying to understand the world. And although many IR scholars do look at things like psychology and state-specific factors to explain foreign policy, they generally don’t take the critique of the unitary actor model far enough. The more I studied the specifics of American foreign policy the more it looked irrational on a system-wide level and unconnected to any reasonable goals, which further made me skeptical of the assumptions of the field.

That’s pretty abstract, so let’s make it concrete. Think about the most consequential foreign policy decision of the last half century. Why did America invade Iraq in 2003?

More here.