Michael S. Roth in The LA Review of Books:

Michael S. Roth in The LA Review of Books:

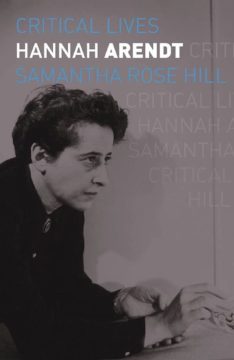

SAMANTHA ROSE HILL’s intellectual biography of Hannah Arendt is a timely look at one of the most impactful, if elusive, 20th-century political thinkers. The book makes accessible key themes in Arendt’s work. Looking for a philosophical focus on creative work that escapes the mystical Teutonic fog of Heidegger? See the concept of natality described in The Human Condition. Concerned about the rise of populist authoritarianism? The Origins of Totalitarianism remains a bracing read, its conceptual flaws and political agenda less important today than its description of the aspiration to tyrannical control. Want to step back from political relevance to something more primary? Arendt’s late reflections on thinking and judgment will be powerful. In all these cases, and many more, Hill is a thoughtful guide.

The early biography is covered quickly. Hill doesn’t say much about the impact of the death of Hannah’s father, only noting with awkward foreshadowing that the loss did not diminish her “inherent wonder at being in the world.” Be that as it may, we know from Elisabeth Young-Bruehl’s more detailed 1982 biography that the seven-year-old Hannah maintained an unusually sunny disposition for months after her father’s death but a year later began acting out and succumbing to various ailments; Young-Bruehl understood this as Hannah’s way of grieving. The young girl’s family was unobservant, but she learned about her Jewish identity from the everyday antisemitism of the street. After her mother moved to East Prussia, a challenging place to be at the outbreak of World War I, Hannah took comfort in her books. Years later when asked by Günter Gaus why she had read Kant at such a young age, she responded, “I can either study philosophy or I can drown myself, so to speak.”

More here.

Once again, just like clockwork, here comes New Year’s Day. Once again, in a wave sweeping across time zones, the world counts backward from 10. Revelry and other traditions have been pared back this year as the coronavirus pandemic drags into yet another new year. The uncertain — but hopefully better — future will be welcomed in with a mixture of hope and trepidation. It’s an odd holiday. Jan. 1 is no great landmark in the course of human events; it is the anniversary of no remarkable birth, death or battle. The cosmos is not arranged in any particularly auspicious way. It is a date pulled out of a hat, an utterly arbitrary starting line for an eternal, repetitive relay race. The innocent baby takes the baton, sprints out with promise and hope, inevitably to stagger home a shattered old man, beaten down by 365 days of calamity, cruelty and chaos, especially so this year. And another baby invariably waits its turn.

Once again, just like clockwork, here comes New Year’s Day. Once again, in a wave sweeping across time zones, the world counts backward from 10. Revelry and other traditions have been pared back this year as the coronavirus pandemic drags into yet another new year. The uncertain — but hopefully better — future will be welcomed in with a mixture of hope and trepidation. It’s an odd holiday. Jan. 1 is no great landmark in the course of human events; it is the anniversary of no remarkable birth, death or battle. The cosmos is not arranged in any particularly auspicious way. It is a date pulled out of a hat, an utterly arbitrary starting line for an eternal, repetitive relay race. The innocent baby takes the baton, sprints out with promise and hope, inevitably to stagger home a shattered old man, beaten down by 365 days of calamity, cruelty and chaos, especially so this year. And another baby invariably waits its turn. This is the centenary year of “Babbitt,” Sinclair Lewis’s best — and most misunderstood — novel. He had written five inconsequential books that had received respectable if not excited attention. And in 1920 — at the age of 35 — he had written “Main Street,” the most sensationally successful novel of the century to date: hundreds of thousands of copies sold, and a title that came to stand for the values, both narrow-minded and wholesome, of what we now call Middle America.

This is the centenary year of “Babbitt,” Sinclair Lewis’s best — and most misunderstood — novel. He had written five inconsequential books that had received respectable if not excited attention. And in 1920 — at the age of 35 — he had written “Main Street,” the most sensationally successful novel of the century to date: hundreds of thousands of copies sold, and a title that came to stand for the values, both narrow-minded and wholesome, of what we now call Middle America. In a utopia, there’d be an issue for everyone. For me, it was Uncanny X-Men No. 414, which I read on the floor of a Pine Sol–scented Barnes and Noble when I was 11. Seated pretzel-legged in one of the aisles, I found something unexpectedly weighty in the Marvel comic: Abused by his father, a boy literally explodes. A lapsed superhero named Northstar discovers him in his home’s rubble. Northstar is gay, we know, because Professor Xavier, founder of a school for “gifted youngsters” with mutant powers they need to learn how to control, wants to hire the flying, ultrafast Canadian; he’d like to diversify his teaching staff so that his students have homosexual role models.

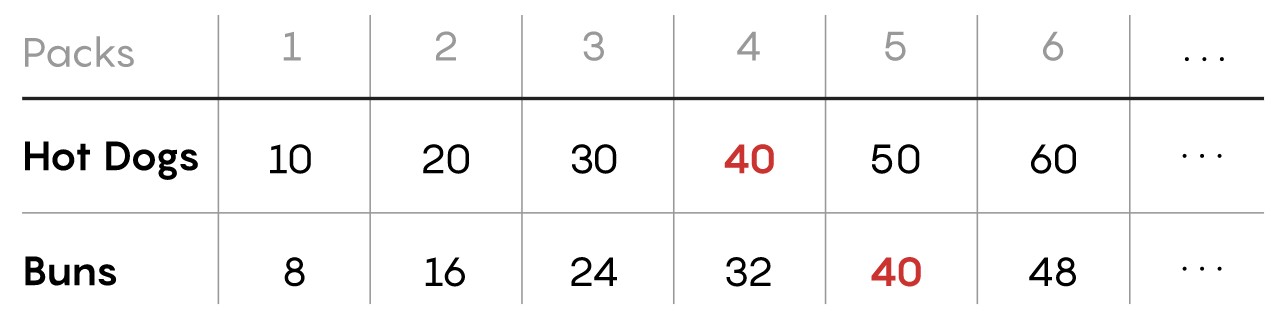

In a utopia, there’d be an issue for everyone. For me, it was Uncanny X-Men No. 414, which I read on the floor of a Pine Sol–scented Barnes and Noble when I was 11. Seated pretzel-legged in one of the aisles, I found something unexpectedly weighty in the Marvel comic: Abused by his father, a boy literally explodes. A lapsed superhero named Northstar discovers him in his home’s rubble. Northstar is gay, we know, because Professor Xavier, founder of a school for “gifted youngsters” with mutant powers they need to learn how to control, wants to hire the flying, ultrafast Canadian; he’d like to diversify his teaching staff so that his students have homosexual role models. If you’ve ever had to buy hot dogs for a cookout, you might have found yourself solving a math problem involving least common multiples. Setting aside the age-old question of why hot dogs usually come in packs of 10 while buns come in packs of eight (you can read what the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council has to say about it

If you’ve ever had to buy hot dogs for a cookout, you might have found yourself solving a math problem involving least common multiples. Setting aside the age-old question of why hot dogs usually come in packs of 10 while buns come in packs of eight (you can read what the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council has to say about it

The term deaths of despair comes from Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton, who set out to understand what accounted for falling U.S. life expectancies. They learned that the

The term deaths of despair comes from Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton, who set out to understand what accounted for falling U.S. life expectancies. They learned that the  Is the American Dream still alive? If you speak to many of the immigrants we spoke to, who came to this country with nothing but grit, resilience, and a dream, they will tell you that it certainly is still alive. As a part of our series about

Is the American Dream still alive? If you speak to many of the immigrants we spoke to, who came to this country with nothing but grit, resilience, and a dream, they will tell you that it certainly is still alive. As a part of our series about  In the fall of 1972, a psychiatrist named Salvador Roquet travelled from his home in Mexico City to the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, an institution largely funded by the United States government, to give a presentation on an ongoing experiment. For several years, Roquet had been running a series of group-therapy sessions: over the course of eight or nine hours, his staff would administer psilocybin mushrooms, morning-glory seeds, peyote cacti, and the herb datura to small groups of patients. He would then orchestrate what he called a “sensory overload show,” with lights, sounds, and images from violent or erotic movies. The idea was to push the patients through an extreme experience to a psycho-spiritual rebirth. One of the participants, an American psychology professor, described the session as a “descent into hell.” But Roquet wanted to give his patients smooth landings, and so, eventually, he added a common hospital anesthetic called ketamine hydrochloride. He found that, given as the other drugs were wearing off, it alleviated the anxiety brought on by these punishing ordeals.

In the fall of 1972, a psychiatrist named Salvador Roquet travelled from his home in Mexico City to the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, an institution largely funded by the United States government, to give a presentation on an ongoing experiment. For several years, Roquet had been running a series of group-therapy sessions: over the course of eight or nine hours, his staff would administer psilocybin mushrooms, morning-glory seeds, peyote cacti, and the herb datura to small groups of patients. He would then orchestrate what he called a “sensory overload show,” with lights, sounds, and images from violent or erotic movies. The idea was to push the patients through an extreme experience to a psycho-spiritual rebirth. One of the participants, an American psychology professor, described the session as a “descent into hell.” But Roquet wanted to give his patients smooth landings, and so, eventually, he added a common hospital anesthetic called ketamine hydrochloride. He found that, given as the other drugs were wearing off, it alleviated the anxiety brought on by these punishing ordeals. When Abdulrazak Gurnah was growing up in the 1950s in Zanzibar, a small island off the east African coast, he could not imagine a career as a writer. Though there were poets and storytellers, there were no literary publishers. At school he was taught the English canon. “You realise, in that literature, you’re completely and totally absent,” he tells me, “or present in some kind of diminished form.” But after moving to Britain in 1968, he did become a writer and, across 10 novels, has drawn on his island’s rich history to fill in those absences. In October, this quietly spoken man—always respected but hardly a household name—won the Nobel Prize in literature.

When Abdulrazak Gurnah was growing up in the 1950s in Zanzibar, a small island off the east African coast, he could not imagine a career as a writer. Though there were poets and storytellers, there were no literary publishers. At school he was taught the English canon. “You realise, in that literature, you’re completely and totally absent,” he tells me, “or present in some kind of diminished form.” But after moving to Britain in 1968, he did become a writer and, across 10 novels, has drawn on his island’s rich history to fill in those absences. In October, this quietly spoken man—always respected but hardly a household name—won the Nobel Prize in literature. T

T On Saturday, September 11, Evander Holyfield, who turned 59 in October, was knocked out in the first round by the 44-year old former UFC champion, Vitor Belfort, in a commission sanctioned bout in Florida.

On Saturday, September 11, Evander Holyfield, who turned 59 in October, was knocked out in the first round by the 44-year old former UFC champion, Vitor Belfort, in a commission sanctioned bout in Florida. Every student of evolution will be familiar with the peppered moth, Biston betularia. It is right up there with the Galápagos finches as an example of evolution happening right under our noses. The story of the rapid spread of dark moths in response to the soot deposition that accompanied the Industrial Revolution, and the reversal of this pattern when air pollution abated, is iconic. Yet, as Emeritus Professor of biology Bruce S. Grant shows, there are a lot more subtleties to it than my one-liner suggests. Observing Evolution details research by himself and many others, and along the way addresses criticism – legitimate and otherwise – levelled at some of the earlier research. Eminently readable, this is a personal story of the rise, fall, and ultimate redemption of one of the most famous textbook examples of evolution in action.

Every student of evolution will be familiar with the peppered moth, Biston betularia. It is right up there with the Galápagos finches as an example of evolution happening right under our noses. The story of the rapid spread of dark moths in response to the soot deposition that accompanied the Industrial Revolution, and the reversal of this pattern when air pollution abated, is iconic. Yet, as Emeritus Professor of biology Bruce S. Grant shows, there are a lot more subtleties to it than my one-liner suggests. Observing Evolution details research by himself and many others, and along the way addresses criticism – legitimate and otherwise – levelled at some of the earlier research. Eminently readable, this is a personal story of the rise, fall, and ultimate redemption of one of the most famous textbook examples of evolution in action. Ever since I started studying IR, I had a gnawing feeling that something about the whole enterprise was off. As I read more history, and also in other fields like economics, anthropology and psychology, I came to the conclusion that the ways in which we talk about international relations and foreign policy are simply wrong. The whole reason that IR is its own subfield in political science is because of the “unitary actor model,” or the assumption that you can talk about a nation like you talk about an individual, with motivations, goals, and strategies. No one believes this in a literal sense, but it’s considered “close enough” for the sake of trying to understand the world. And although many IR scholars do look at things like psychology and state-specific factors to explain foreign policy, they generally don’t take the critique of the unitary actor model far enough. The more I studied the specifics of American foreign policy the more it

Ever since I started studying IR, I had a gnawing feeling that something about the whole enterprise was off. As I read more history, and also in other fields like economics, anthropology and psychology, I came to the conclusion that the ways in which we talk about international relations and foreign policy are simply wrong. The whole reason that IR is its own subfield in political science is because of the “unitary actor model,” or the assumption that you can talk about a nation like you talk about an individual, with motivations, goals, and strategies. No one believes this in a literal sense, but it’s considered “close enough” for the sake of trying to understand the world. And although many IR scholars do look at things like psychology and state-specific factors to explain foreign policy, they generally don’t take the critique of the unitary actor model far enough. The more I studied the specifics of American foreign policy the more it  WHAT’S COMMONLY KNOWN ABOUT THE PORTUGUESE WRITER FERNANDO PESSOA is that he died young-ish at the age of forty-seven in 1935, drank heavily, and assigned authorship of his work to over a hundred “heteronyms,” pen names that carry more biographical heft than the average alias. Pessoa died having published only one book of poetry in Portuguese (Mensagem) and two self-published chapbooks of English-language poetry. The lion’s share of his work was found in a trunk containing about 25,000 pages of writings. Without much of a public record of his life as he lived it, celebrating Pessoa and researching Pessoa have always been roughly the same thing. Few have done as much of that work as Richard Zenith, an American who has translated a chunk of the Pessoa oeuvre and put in more than ten years writing an extremely definitive biography of a shape-shifting weirdo his country adores. When I was in Lisbon in 2018, a cab driver, unprompted, recited one of his poems to me on our way to the Casa Fernando Pessoa, a museum and historical site. More officially, Pessoa’s face was on the 100 escudo note before the euro fully replaced it in 2002. His mutating nationalism might be what made him a candidate for Portuguese pride, though his politics were hardly consistent.

WHAT’S COMMONLY KNOWN ABOUT THE PORTUGUESE WRITER FERNANDO PESSOA is that he died young-ish at the age of forty-seven in 1935, drank heavily, and assigned authorship of his work to over a hundred “heteronyms,” pen names that carry more biographical heft than the average alias. Pessoa died having published only one book of poetry in Portuguese (Mensagem) and two self-published chapbooks of English-language poetry. The lion’s share of his work was found in a trunk containing about 25,000 pages of writings. Without much of a public record of his life as he lived it, celebrating Pessoa and researching Pessoa have always been roughly the same thing. Few have done as much of that work as Richard Zenith, an American who has translated a chunk of the Pessoa oeuvre and put in more than ten years writing an extremely definitive biography of a shape-shifting weirdo his country adores. When I was in Lisbon in 2018, a cab driver, unprompted, recited one of his poems to me on our way to the Casa Fernando Pessoa, a museum and historical site. More officially, Pessoa’s face was on the 100 escudo note before the euro fully replaced it in 2002. His mutating nationalism might be what made him a candidate for Portuguese pride, though his politics were hardly consistent.