Category: Recommended Reading

The Dragnet

Gautam Pemmaraju in Fiftytwo.

Gautam Pemmaraju in Fiftytwo.

The danger comes from the east, coloured red. Having brought down the tsar in Russia, the Soviet communists are now looking outwards with a grand plan. Vladimir Lenin has already discarded the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 and is calling on the Asian people to overthrow their colonial oppressors. Just two years earlier, he’d announced: “England is our greatest enemy. It is in India we must strike them hardest.”

The Bolsheviks now have operations in India to “penetrate the existing nationalist movement.” Meanwhile, the British already have a lot to contend with. Indian nationalists are clamouring for swaraj. The country is convulsed by workers’ strikes. There are periodic violent attacks on British officials. India’s Muslims are seething over the dismemberment of Ottoman Turkey. Bombay is a tinderbox, waiting to be sparked.

At the centre of Lenin’s plans is one man: Manabendra Nath Roy.

On that day in 1922, officers of the Foreign Branch of the Criminal Investigation Department are on alert for any and all suspicious characters. An agent of M.N. Roy could try to slip through with banned books, manifestos and money. The man himself might show up to direct the revolutionary movement from within.

To the British, the ‘red peril’ is nothing less than terrorism. The Great Game of the empires for strategic control over Central Asia has mutated and Moscow is plotting to foment global revolutions, to violently overthrow capitalists and imperialists. Any intervention has the potential to strengthen nationalist and anti-colonial movements across the realm. And losing India, everyone knows, would be the beginning of the end for the Empire.

More here.

Theories, Facts, and Lisa Cook

Paul Romer over at his his website:

Paul Romer over at his his website:

John Cochrane used a theory about Lisa Cook to dismiss her as a member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. I know Lisa well enough to know that John’s theory does not fit the facts.

I respect both John and Lisa as economists but recognize how they differ. John is a theorist. Lisa is an empiricist. Of the two, I would rather have Lisa on the Board of Governors because she is more attentive to the facts.

I may not be able to convince John that she is better suited to the job than he, but perhaps I can persuade him that she is better suited than I, a theorist like John.

Rule of Law and Economic Growth

I proposed a theory in which growth happens because of things that people do. The abstract implication of this theory is that good policy can increase the rate of growth by encouraging people to do more of those things. The practical policy implication seemed to be that improving contract law and offering more protection for intellectual property rights would be one of the most direct ways to increase a nation’s rate of growth.

In a paper available here or here, Lisa presents evidence that she spent many years accumulating about a crucial point that this line of reasoning missed. She used patenting as a proxy for the activities that spur growth and assembled convincing evidence that there is another part of the legal system that has a bigger effect: the degree to which it creates a climate of personal security by protecting citizens from the threat of violence.

This insight could be of first order significance for our understanding of differences in national rates of growth.

More here.

Birju Maharaj (1937 – 2022) dancer

Monica Vitti (1931 – 2022) actor

Carol Speed (1945 – 2022) actor

Sunday Poem

House Slave

The first horn lifts its arm over the dew-lit grass

and in the slave quarters there is a rustling—

children are bundled into aprons, cornbread

and water gourds grabbed, a salt pork breakfast taken.

I watch them driven into the vague before-dawn

while their mistress sleeps like an ivory toothpick

and Massa dreams of asses, rum and slave-funk.

I cannot fall asleep again. At the second horn,

the whip curls across the backs of the laggards—

sometimes my sister’s voice, unmistaken, among them.

“Oh! pray,” she cries. “Oh! pray!” Those days

I lie on my cot, shivering in the early heat,

and as the fields unfold to whiteness,

and they spill like bees among the fat flowers,

I weep. It is not yet daylight.

by Rita Dove

from Selected Poems

W.W. Norton, 1993

Black Literature – Past, Present and Future: A Reading List

From PEN America:

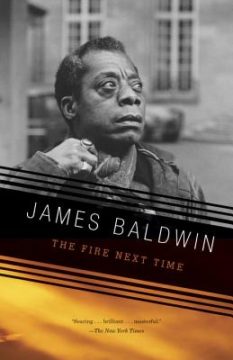

This week’s reading list is curated by PEN America’s World Voices Festival team and features a mix of classic and contemporary novels, essay collections, and poetry collections. It includes the searing prose of James Baldwin’s 1963 bestseller The Fire Next Time, in which he tells his nephew how to navigate the injustices he will face as Black man in America. We also highlight Nic Stone’s Dear Martin, published more than 50 years later but which exposes the same threats of racial violence that still plague our country and threaten young Black men.

This week’s reading list is curated by PEN America’s World Voices Festival team and features a mix of classic and contemporary novels, essay collections, and poetry collections. It includes the searing prose of James Baldwin’s 1963 bestseller The Fire Next Time, in which he tells his nephew how to navigate the injustices he will face as Black man in America. We also highlight Nic Stone’s Dear Martin, published more than 50 years later but which exposes the same threats of racial violence that still plague our country and threaten young Black men.

We chose the works on this list because, like Baldwin’s essay and Stone’s YA novel, they are in conversation with one another. They inform one another, build off of one another, and celebrate one another. They do not just detail the plight of Black people. Rather, these works of art, like any example of great literature, are nuanced, challenging, and boundless. History has proven that interest in Black literature surges during periods of social unrest. But the canon of Black literature did not suddenly appear in these moments. Black literature is American literature.

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin (1963)

Baldwin’s powerful essays evoke his upbringing while calling into attention the racial violence that plagued the United States at the start of the Civil Rights Movement. The text, which contains two “letters,” written on the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation, quickly became a bestseller and galvanized the nation.

More here. (Note: At least one post throughout the month of February will be devoted to Black History Month. The theme for 2022 is Black Health and Wellness)

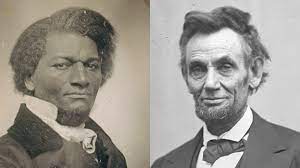

Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass: Inside Their Complicated Relationship

Farrell Evans in History:

In the middle of the 19th century, as the United States was ensnared in a bloody Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln and abolitionist Frederick Douglass stood as the two most influential figures in the national debate over slavery and the future of African Americans. They met together three times in the White House, and while Douglass was at first harshly critical, he ultimately came to view Lincoln as “emphatically the Black man’s president: the first to show any respect for their rights as men.”

In the middle of the 19th century, as the United States was ensnared in a bloody Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln and abolitionist Frederick Douglass stood as the two most influential figures in the national debate over slavery and the future of African Americans. They met together three times in the White House, and while Douglass was at first harshly critical, he ultimately came to view Lincoln as “emphatically the Black man’s president: the first to show any respect for their rights as men.”

The first time they met, in August 1863, Douglass was perhaps the most famous Black man in the world. Since escaping from slavery to the North in 1838, he had written two bestselling autobiographies that recounted his journey from a Maryland plantation to lecture halls all over the world as a leading anti-slavery crusader, journal publisher and champion for African American rights. With the Civil War in full stride, Douglass was advocating for the equal treatment of Black Union soldiers. In March, he had issued his famous “MEN OF COLOR to ARMS! broadside calling for Black men to enlist in the Union army. Two of his sons had joined the 54th Massachusetts Black regiment.

More here. (Note: At least one post throughout the month of February will be devoted to Black History Month. The theme for 2022 is Black Health and Wellness)

Saturday, February 5, 2022

Death Drive Nation

Patrick Blanchfield in Late-Lite:

Patrick Blanchfield in Late-Lite:

In the busy holiday rush of December 2019, a 27-year-old UPS driver named Frank Ordóñez, who had the day off, volunteered to cover a shift for his friend. On his route delivering packages through the suburbs of Miramar, Florida, Ordóñez was carjacked and held at gunpoint by two men who had just robbed and shot up a nearby jewelry store. The police were hot on their heels, and a car chase ensued. Audiences watched on TV, the footage broadcast live by news helicopters, as the big brown van turned onto Interstate 75, Ordóñez still inside.

The chase proceeded for twenty miles. When rush-hour traffic slowed to a crawl, police representing three separate departments leapt from their vehicles and swarmed in. Bobbing and weaving for cover behind the cars of terrified commuters, they exchanged fire with the carjackers, ultimately surrounding and emptying their weapons into the UPS van. Nineteen officers let off some 200 rounds. In minutes, both carjackers were dead, as were Ordóñez and a 70-year-old bystander named Richard Cutshaw.

Within hours of Ordóñez’s death, his employer released a statement thanking the police for their role in killing him. “We are deeply saddened to learn a UPS service provider was a victim of this senseless act of violence,” ran the company’s statement that evening. “We extend our condolences to the family and friends of our employee and the other innocent victims involved in the incident. We appreciate law enforcement’s service and will cooperate with the authorities as they continue the investigation.”

More here.

Acute Dollar Dominance

Mona Ali in Phenomenal World:

Mona Ali in Phenomenal World:

In early 2020, the “dash for cash” in the US Treasury market prompted the Fed to relaunch its dollar swap lines, which it did in mid-March of that year. In the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the New York Fed had established permanent arrangements to supply dollars to five key foreign central banks. But as the emerging pandemic rattled global financial markets, dollar swaps were temporarily extended to nine more foreign central banks. Less privileged foreign central banks not extended such swap lines were instead given access to the Fed’s brand-new Foreign and International Monetary Authorities (FIMA) repurchase agreement facility, which allowed them to exchange their US Treasury securities for dollars as an alternative to dumping the securities for cash in the open market. The move was part of a concerted suite of measures undertaken by the Fed to stabilize dollar funding markets. (Compared to peak swap use of $449 billion, FIMA Repo use peaked at a relatively paltry $1 billion.) That spring, the Fed balance sheet mushroomed from $4 to $7 trillion. The Fed’s decisive actions quashed any doubt that the world’s most powerful central bank would hesitate to assume the mantle of monetary hegemony. As of the beginning of 2022, Fed assets stand close to $9 trillion.

The coronavirus crisis highlighted stark disparities in financing capacity across the globe. Monetary and fiscal relief amounted to one-fifth of GDP in advanced economies, only six or seven percent of output in smaller economies, and a mere two percent of GDP in the poorest of nations. The US macroeconomy’s rebound—steeper than that of any other rich economy—is an outcome of its $5-trillion-plus stimulus. In 2021, per capita growth in low-income economies was a tenth of that in advanced economies, foregrounding the starkly divergent paths of economic recovery. Increased government spending in response to the pandemic birthed deficits and debt in advanced economies that were twice the size of those in poorer economies. However, given the strictures placed on poorer nations by the international financial hierarchy, for some financially subordinated economies, public debt accumulation has brought sovereign debt default closer to the horizon.

More here.

How the Method Made Acting Modern

Alexandra Schwartz in The New Yorker:

In January, 1923, Lee Strasberg went to Al Jolson’s 59th Street Theatre to see “Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich,” a nineteenth-century Russian play about sixteenth-century Russian politics, performed, in Russian, by a company called the Moscow Art Theatre. Strasberg, twenty-one years old, was born in a Polish shtetl and brought up on the Lower East Side. He worked as a bookkeeper for a business that sold human hair. He didn’t know Russian.

What he knew was acting. As a kid, Strasberg had performed in a few plays—his brother-in-law did the makeup for an amateur Yiddish theatre troupe—and by the time he graduated from high school he had fallen headlong in love with the theatre. He went to show after show on Broadway, where he saw extraordinary performances by some of the great actors of the day: Jeanne Eagels, Giovanni Grasso, Eleonora Duse. Other performances should have been extraordinary but weren’t. Sometimes an actor seemed to glow with a private, ineffable fire, only to lose the spark halfway through the play. Or an actor might start off stiff and flat and then suddenly flare with “inner life.”

Strasberg began to think about what made some performances succeed and some fail, and concluded that it must have to do with whether or not the actor was feeling inspired. This presented its own dilemma, because inspiration is hellishly inconsistent. You can’t just flip a switch and expect an inner bulb to go on. Or can you?

More here.

Adorno’s damaged life

Peter E. Gordon in The New Statesman:

Peter E. Gordon in The New Statesman:

Minima Moralia is a work of exile. Published just over 70 years ago in 1951, the greater share of it was written at the conclusion of the Second World War, when its German-born author Theodor Wiesengrund Adorno was living in Los Angeles County, not far from other artists and intellectuals who had the good fortune to escape the Third Reich. “The violence that expelled me,” he explained, left him with an enduring sense of guilt at the very fact of his survival. The book’s subtitle, “Reflections from Damaged Life”, is a record of this unhealed wound, a bitter confession that even to write about individual experience suggests a complicity with “unspeakable collective events”. But Adorno worked at the trauma and made of it an irritant for thinking, sand for the pearls of insight that would fill each page. It is the most personal book he ever wrote, and even at the highest peaks of abstraction, it does not efface its origins in autobiography. Not unlike the Essais by the 16th-century humanist Michel de Montaigne, Adorno’s book is not only a series of philosophical experiments but also an exercise in self-portraiture. What Adorno calls “subjective experience” must serve as a permanent element for all criticism if it does not wish to contribute to the further destruction of humanity.

How can we classify an intellectual who abhorred classification? Critical of all group loyalty and always distancing himself from his social surroundings, Adorno was a cosmopolitan intellectual who carried his erudition on his back as the only possession that mattered.

More here.

‘Adam’: S Hareesh’s collection of short stories is a disturbingly real study of dark human behaviour

Saloni Sharma in Scroll.in:

Chances are, if you haven’t been living under a pandemic-shaped rock of ascetic withdrawal from the real world, you will have heard of S Hareesh. His debut novel, Meesha, translated from the Malayalam into English as Moustache, won the JCB Prize for Literature in 2020. India’s 2020 official entry to the Academy Awards, Jallikattu, was based on one of Hareesh’s short stories from the collection Adam, which won the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award of 2016. This same award-winning anthology of nine stories has been translated into English by Jayasree Kalathil – and what a stunner of a collection it is.

Chances are, if you haven’t been living under a pandemic-shaped rock of ascetic withdrawal from the real world, you will have heard of S Hareesh. His debut novel, Meesha, translated from the Malayalam into English as Moustache, won the JCB Prize for Literature in 2020. India’s 2020 official entry to the Academy Awards, Jallikattu, was based on one of Hareesh’s short stories from the collection Adam, which won the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award of 2016. This same award-winning anthology of nine stories has been translated into English by Jayasree Kalathil – and what a stunner of a collection it is.

Towards a posthumanist aesthetic

There is so much going on in the stories that make up Adam. Hareesh makes a disturbingly real study of human behaviour, of the slivers of darkness that lurk under the surface of urbanity, of a playfulness that doesn’t quite know how to co-exist with the serious business of living. However, what catches the reader’s attention, perhaps more than anything else, is the distinct shift from an anthropocentric to a posthumanist aesthetic.

More here.

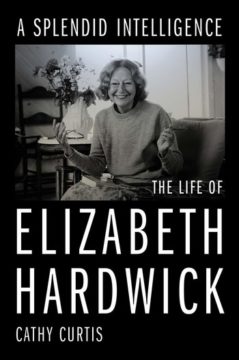

Elizabeth Hardwick: The Life Of An Essential Writer

Christian Lorentzen at Bookforum:

The case of Elizabeth Hardwick is vexing in these ways and more. She was one of the supreme women of letters in postwar America. The scope of her achievement, much of it accomplished in occasional writings undertaken across six decades, has only begun to come into view with the appearance in 2017 of her Collected Essays. (A volume of Uncollected Essays is to follow this spring.) She chronicled the transformations of American life and culture across seven decades, traced the progress of American literature from its beginnings here and in Europe, connected those roots and parallel strands to the present in essays of idiosyncratic synthesis, and realized those ideas in her own fictions. She was a singular stylist and an essential writer of her time.

The case of Elizabeth Hardwick is vexing in these ways and more. She was one of the supreme women of letters in postwar America. The scope of her achievement, much of it accomplished in occasional writings undertaken across six decades, has only begun to come into view with the appearance in 2017 of her Collected Essays. (A volume of Uncollected Essays is to follow this spring.) She chronicled the transformations of American life and culture across seven decades, traced the progress of American literature from its beginnings here and in Europe, connected those roots and parallel strands to the present in essays of idiosyncratic synthesis, and realized those ideas in her own fictions. She was a singular stylist and an essential writer of her time.

more here.

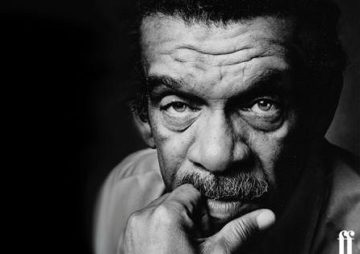

Saturday Poem

Love after Love

The time will come

when, with elation,

you will greet yourself arriving

at your own door, in your own mirror,

and each will smile at the other’s welcome,

and say, sit here. Eat.

You will love again the stranger who was yourself.

Give wine. Give bread. Give back your heart

to itself, to the stranger who has loved you

all your life, whom you ignored

for another, who knows you by heart.

Take down the love letters from the bookshelf,

the photographs, the desperate notes,

peel your own image from the mirror.

Sit. Feast on your life.

by Derek Walcott

from Derek Walcott Collected Poems

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1986

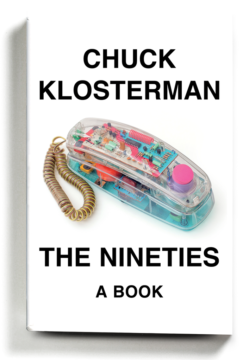

Chuck Klosterman Rewinds to ‘The Nineties’

Alexandra Jacobs at the NYT:

The era has lately been a source of curiosity, its aesthetic mined by digital natives who marvel at the freedom of a world where people partied and presented themselves without being haunted by their online shadows. “Every new generation tends to be intrigued by whatever generation existed 20 years earlier,” Klosterman writes. This particular look back has special romance, since, as he writes mock-portentously, “The internet was coming. The internet was coming. The internet was coming.” But the internet as we know it wasn’t quite there yet.

The era has lately been a source of curiosity, its aesthetic mined by digital natives who marvel at the freedom of a world where people partied and presented themselves without being haunted by their online shadows. “Every new generation tends to be intrigued by whatever generation existed 20 years earlier,” Klosterman writes. This particular look back has special romance, since, as he writes mock-portentously, “The internet was coming. The internet was coming. The internet was coming.” But the internet as we know it wasn’t quite there yet.

The 1990s were the twilight of a millennium and a monoculture (such as it was); the last time we (whoever “we” were) seemed to be on the same page: one we could crinkle in our hands.

more here.

Als, Hamilton, and Chalfant On Hardwick And Lowell

Why The Black Lives Matter Movement Matters to Me ( BLAM UK Essay Competition) By Sarah Fowler Aged-13

Sarah Fowler in BLAM:

The BLM movement was founded on the 13th July 2013, by Alicia Garza; Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi. The movement was made to promote anti-racism and advocacy, it is often interpreted in the incorrect way by people who do not recognise how Black people are often victims of demonisation as well as criminalisation. This often results in people making ignorant comments that make it clear that the purpose of the movement was taken out of context: ‘ ALL LIVES MATTER ‘ they incessantly yell; ‘ Why is it always about race? Can’t you just get over it??’ they say way too passive-aggressively not knowing the true meaning of what we’re fighting for. We are fighting for the lives that were taken for reasons that only remain superficial, we are fighting for the next generation of people who go looked just like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Atatiana Jefferson, Stephon Clark, Michelle Cusseaux and the others that have died. They were killed for reasons that will only remain skin deep, and this time, it will not be in vain or go unnoticed.

The BLM movement was founded on the 13th July 2013, by Alicia Garza; Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi. The movement was made to promote anti-racism and advocacy, it is often interpreted in the incorrect way by people who do not recognise how Black people are often victims of demonisation as well as criminalisation. This often results in people making ignorant comments that make it clear that the purpose of the movement was taken out of context: ‘ ALL LIVES MATTER ‘ they incessantly yell; ‘ Why is it always about race? Can’t you just get over it??’ they say way too passive-aggressively not knowing the true meaning of what we’re fighting for. We are fighting for the lives that were taken for reasons that only remain superficial, we are fighting for the next generation of people who go looked just like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Atatiana Jefferson, Stephon Clark, Michelle Cusseaux and the others that have died. They were killed for reasons that will only remain skin deep, and this time, it will not be in vain or go unnoticed.

After their deaths gained publicity by the ‘Black lives matter’ movement, they were angered that no action was being taken except from being fired. ‘No justice, No peace!’ they scream as they walk the streets begging for justice. Protests started not only in America but all over the world. These protests started peacefully, and even so the police sprayed them with tear gas and rubber bullets, and even some cases real bullets. ‘Blue lives matter’ they say. ‘NO, All lives matter!’ they cry. These phrases are derived from Black lives matter and using them implies you are attempting to degrade black people for our efforts to ask for justice as well as to contrive the meaning of the BLM movement to these other ‘movements’. Blue lives matter was made for cops who are killed in the job they chose to work for, knowing the risks, knowing the time it would eat up, they CHOSE to be an officer. A black person cannot take off their skin like an officer takes their uniform after duty. All lives matter was made to say ‘All races matter, not just black people!’ not knowing that the black race is like a burning house asking to be taken care of while other people are asking for there to be dealt with when their houses have no complications.

More here. (Note: At least one post throughout the month of February will be devoted to Black History Month. The theme for 2022 is Black Health and Wellness)

Friday, February 4, 2022

Erich Fromm – The Art of Love (1989)