Sarah Fowler in BLAM:

The BLM movement was founded on the 13th July 2013, by Alicia Garza; Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi. The movement was made to promote anti-racism and advocacy, it is often interpreted in the incorrect way by people who do not recognise how Black people are often victims of demonisation as well as criminalisation. This often results in people making ignorant comments that make it clear that the purpose of the movement was taken out of context: ‘ ALL LIVES MATTER ‘ they incessantly yell; ‘ Why is it always about race? Can’t you just get over it??’ they say way too passive-aggressively not knowing the true meaning of what we’re fighting for. We are fighting for the lives that were taken for reasons that only remain superficial, we are fighting for the next generation of people who go looked just like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Atatiana Jefferson, Stephon Clark, Michelle Cusseaux and the others that have died. They were killed for reasons that will only remain skin deep, and this time, it will not be in vain or go unnoticed.

The BLM movement was founded on the 13th July 2013, by Alicia Garza; Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi. The movement was made to promote anti-racism and advocacy, it is often interpreted in the incorrect way by people who do not recognise how Black people are often victims of demonisation as well as criminalisation. This often results in people making ignorant comments that make it clear that the purpose of the movement was taken out of context: ‘ ALL LIVES MATTER ‘ they incessantly yell; ‘ Why is it always about race? Can’t you just get over it??’ they say way too passive-aggressively not knowing the true meaning of what we’re fighting for. We are fighting for the lives that were taken for reasons that only remain superficial, we are fighting for the next generation of people who go looked just like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Atatiana Jefferson, Stephon Clark, Michelle Cusseaux and the others that have died. They were killed for reasons that will only remain skin deep, and this time, it will not be in vain or go unnoticed.

After their deaths gained publicity by the ‘Black lives matter’ movement, they were angered that no action was being taken except from being fired. ‘No justice, No peace!’ they scream as they walk the streets begging for justice. Protests started not only in America but all over the world. These protests started peacefully, and even so the police sprayed them with tear gas and rubber bullets, and even some cases real bullets. ‘Blue lives matter’ they say. ‘NO, All lives matter!’ they cry. These phrases are derived from Black lives matter and using them implies you are attempting to degrade black people for our efforts to ask for justice as well as to contrive the meaning of the BLM movement to these other ‘movements’. Blue lives matter was made for cops who are killed in the job they chose to work for, knowing the risks, knowing the time it would eat up, they CHOSE to be an officer. A black person cannot take off their skin like an officer takes their uniform after duty. All lives matter was made to say ‘All races matter, not just black people!’ not knowing that the black race is like a burning house asking to be taken care of while other people are asking for there to be dealt with when their houses have no complications.

More here. (Note: At least one post throughout the month of February will be devoted to Black History Month. The theme for 2022 is Black Health and Wellness)

But, of course, there is no reason for believing any of this; and it seems far more likely that the process of replacing one’s neurons with computer chips would be little more than a very slow process of suicide, producing not the same behaviors as would a living mind, but only progressive derangement and stupefaction, culminating in an inert mass of diffusely galvanized circuitry. After all, any sober phenomenology of the full range of mental acts discloses a host of necessarily unified features that are almost by definition irreducible to a mere integration of diverse mechanical parts and discrete functions, and that no process of computation could reproduce: subjectivity as an indissoluble privacy; the unified and simultaneous field of apprehension belonging to that subjectivity; qualitative consciousness; intentionality and its intrinsic teleology; the indeterminate openness of the mind to novelty and even to fundamental revisions of its conceptual paradigms, which no computational algorithm could simulate; the immediate physical sense of self; the psychological sense of identity; judgments of value, such as “good” or “true” or “beautiful”; the prior and constant disposition of the mind toward these values, which seems to be the necessary motive of all movements of intellect and will toward the world; creative violations of rules that nevertheless make “sense” to us; and so on.

But, of course, there is no reason for believing any of this; and it seems far more likely that the process of replacing one’s neurons with computer chips would be little more than a very slow process of suicide, producing not the same behaviors as would a living mind, but only progressive derangement and stupefaction, culminating in an inert mass of diffusely galvanized circuitry. After all, any sober phenomenology of the full range of mental acts discloses a host of necessarily unified features that are almost by definition irreducible to a mere integration of diverse mechanical parts and discrete functions, and that no process of computation could reproduce: subjectivity as an indissoluble privacy; the unified and simultaneous field of apprehension belonging to that subjectivity; qualitative consciousness; intentionality and its intrinsic teleology; the indeterminate openness of the mind to novelty and even to fundamental revisions of its conceptual paradigms, which no computational algorithm could simulate; the immediate physical sense of self; the psychological sense of identity; judgments of value, such as “good” or “true” or “beautiful”; the prior and constant disposition of the mind toward these values, which seems to be the necessary motive of all movements of intellect and will toward the world; creative violations of rules that nevertheless make “sense” to us; and so on. Despite its long and extensive literary heritage, and despite being the home of some of the earliest printed books, Qing-dynasty China found itself at a profound disadvantage in the new global information order that evolved in the 19th century as part of the intertwined processes of colonial expansion and globalisation. Foreign powers subordinated China through the deployment of advanced maritime technologies and weaponry. The Qing empire found itself hampered in its efforts to respond by the nature of its written language. Knowledge is power, goes the saying, but not if knowledge cannot be organised, retrieved, transmitted and reproduced.

Despite its long and extensive literary heritage, and despite being the home of some of the earliest printed books, Qing-dynasty China found itself at a profound disadvantage in the new global information order that evolved in the 19th century as part of the intertwined processes of colonial expansion and globalisation. Foreign powers subordinated China through the deployment of advanced maritime technologies and weaponry. The Qing empire found itself hampered in its efforts to respond by the nature of its written language. Knowledge is power, goes the saying, but not if knowledge cannot be organised, retrieved, transmitted and reproduced.

One morning in January, 2020, a group of curators and officials from the Museum of Food and Drink headed out to the industrial edge of Queens to assess the status of their most high-profile acquisition to date: the Ebony Test Kitchen. The kitchen, originally situated on the tenth floor of the Johnson Publishing Company Building, in downtown Chicago, tested recipes for Ebony magazine’s famed “Date with a Dish” cooking column, which became a touchstone of African American cuisine. “This kitchen, it’s like—I don’t even know if calling it the Black Julia Child’s kitchen does it justice, but it is that important,”

One morning in January, 2020, a group of curators and officials from the Museum of Food and Drink headed out to the industrial edge of Queens to assess the status of their most high-profile acquisition to date: the Ebony Test Kitchen. The kitchen, originally situated on the tenth floor of the Johnson Publishing Company Building, in downtown Chicago, tested recipes for Ebony magazine’s famed “Date with a Dish” cooking column, which became a touchstone of African American cuisine. “This kitchen, it’s like—I don’t even know if calling it the Black Julia Child’s kitchen does it justice, but it is that important,”  In the late eighteenth century, while in hiding from his fellow French revolutionaries, the philosopher and mathematician Nicolas de Condorcet posed a question that continues to occupy scientists to this day. “No doubt man will not become immortal,” he wrote in Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind, “but cannot the span constantly increase between the moment he begins to live and the time when naturally, without illness or accident, he finds life a burden?”

In the late eighteenth century, while in hiding from his fellow French revolutionaries, the philosopher and mathematician Nicolas de Condorcet posed a question that continues to occupy scientists to this day. “No doubt man will not become immortal,” he wrote in Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind, “but cannot the span constantly increase between the moment he begins to live and the time when naturally, without illness or accident, he finds life a burden?” If you care about animals, you should eat them. It is not just that you may do so, but you should do so. In fact, you owe it to animals to eat them. It is your duty. Why? Because eating animals benefits them and has benefitted them for a long time. Breeding and eating animals is a very long-standing cultural institution that is a mutually beneficial relationship between human beings and animals. We bring animals into existence, care for them, rear them, and then kill and eat them. From this, we get food and other animal products, and they get life. Both sides benefit. I should say that by ‘animals’ here, I mean nonhuman animals. It is true that we are also animals, but we are also more than that, in a way that makes a difference.

If you care about animals, you should eat them. It is not just that you may do so, but you should do so. In fact, you owe it to animals to eat them. It is your duty. Why? Because eating animals benefits them and has benefitted them for a long time. Breeding and eating animals is a very long-standing cultural institution that is a mutually beneficial relationship between human beings and animals. We bring animals into existence, care for them, rear them, and then kill and eat them. From this, we get food and other animal products, and they get life. Both sides benefit. I should say that by ‘animals’ here, I mean nonhuman animals. It is true that we are also animals, but we are also more than that, in a way that makes a difference. Joanna Lumley, one of the judges the year it won, found the book ‘indefensible’. Decades later, Booker winner

Joanna Lumley, one of the judges the year it won, found the book ‘indefensible’. Decades later, Booker winner  The idea that polarization is the predominant ailment of American democracy looms large in political commentary. It is asserted across the partisan spectrum, taking center stage in President Biden’s Inaugural Address and in recent statements by former Presidents Bush and Carter. The diagnosis resonates with voters as well. Though pronounced in the US, polarization isn’t strictly America’s problem. The UK remains significantly divided over Brexit, and one in five French voters identifies as “extreme.” A pair of researchers has called polarization the new specter haunting Europe. Another team says it is a “global crisis.”

The idea that polarization is the predominant ailment of American democracy looms large in political commentary. It is asserted across the partisan spectrum, taking center stage in President Biden’s Inaugural Address and in recent statements by former Presidents Bush and Carter. The diagnosis resonates with voters as well. Though pronounced in the US, polarization isn’t strictly America’s problem. The UK remains significantly divided over Brexit, and one in five French voters identifies as “extreme.” A pair of researchers has called polarization the new specter haunting Europe. Another team says it is a “global crisis.” The Ulysses centenary is a momentous occasion. It is an event for celebration, but one that prompts the question of what exactly is to be celebrated. The publication of an extraordinary Irish novel? Perhaps, but what precisely is Ulysses’s relationship to the Irish novel tradition that preceded or has followed it? The publication of a work that transformed the inherited form of the novel more generally? Certainly, Ulysses revolutionised the modern novel as form but what sort of revolution did it enact and what was its later issue? How do aesthetic revolutions relate to sociopolitical revolutions? Do they, like the latter, have their radical springtimes and then become autumnally institutionalised and conservative? Or must they each be assessed on quite different terms? That Ulysses was an event nearly everyone will agree. However, can we say even now, a century later, what kind of event it really was in Irish or world literary terms? And is Ulysses really a novel at all in any case?

The Ulysses centenary is a momentous occasion. It is an event for celebration, but one that prompts the question of what exactly is to be celebrated. The publication of an extraordinary Irish novel? Perhaps, but what precisely is Ulysses’s relationship to the Irish novel tradition that preceded or has followed it? The publication of a work that transformed the inherited form of the novel more generally? Certainly, Ulysses revolutionised the modern novel as form but what sort of revolution did it enact and what was its later issue? How do aesthetic revolutions relate to sociopolitical revolutions? Do they, like the latter, have their radical springtimes and then become autumnally institutionalised and conservative? Or must they each be assessed on quite different terms? That Ulysses was an event nearly everyone will agree. However, can we say even now, a century later, what kind of event it really was in Irish or world literary terms? And is Ulysses really a novel at all in any case? In the spring of 1953, a former Nazi named Anton Melchers, who in the Third Reich had been a newspaper editor, war reporter, and—according to his brother—talented propagandist, was admitted to the university psychiatric clinic in Heidelberg. His brother, a former high-ranking SS officer, brought him there because Melchers had stopped eating. At the clinic, Melchers reported hearing voices that accused him of sexual immorality and intimated that he would be “paraded” in the streets. Melchers was also preoccupied, his brother said, with anxieties about being “rounded up and taken away” as punishment for his National Socialist past.

In the spring of 1953, a former Nazi named Anton Melchers, who in the Third Reich had been a newspaper editor, war reporter, and—according to his brother—talented propagandist, was admitted to the university psychiatric clinic in Heidelberg. His brother, a former high-ranking SS officer, brought him there because Melchers had stopped eating. At the clinic, Melchers reported hearing voices that accused him of sexual immorality and intimated that he would be “paraded” in the streets. Melchers was also preoccupied, his brother said, with anxieties about being “rounded up and taken away” as punishment for his National Socialist past.

In 1152, a curious scene unfolded outside the

In 1152, a curious scene unfolded outside the  The phrase “black lives matter” was born in July of 2013, in a Facebook post by Alicia Garza, called “a love letter to black people.” The post was intended as an affirmation for a community distraught over George Zimmerman’s acquittal in the shooting death of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin, in Sanford, Florida. Garza, now thirty-five, is the special-projects director in the Oakland office of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, which represents twenty thousand caregivers and housekeepers, and lobbies for labor legislation on their behalf. She is also an advocate for queer and transgender rights and for anti-police-brutality campaigns.

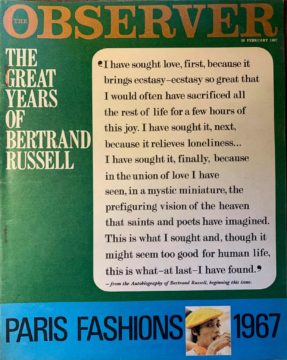

The phrase “black lives matter” was born in July of 2013, in a Facebook post by Alicia Garza, called “a love letter to black people.” The post was intended as an affirmation for a community distraught over George Zimmerman’s acquittal in the shooting death of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin, in Sanford, Florida. Garza, now thirty-five, is the special-projects director in the Oakland office of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, which represents twenty thousand caregivers and housekeepers, and lobbies for labor legislation on their behalf. She is also an advocate for queer and transgender rights and for anti-police-brutality campaigns. The Observer Magazine has never again featured an extract from the autobiography of a philosopher on its cover after ‘The Great Years of Bertrand Russell’, 26 February 1967.

The Observer Magazine has never again featured an extract from the autobiography of a philosopher on its cover after ‘The Great Years of Bertrand Russell’, 26 February 1967. New high-speed cellphone services have raised concerns of interference with aircraft operations, particularly as aircraft are landing at airports. The Federal Aviation Administration has

New high-speed cellphone services have raised concerns of interference with aircraft operations, particularly as aircraft are landing at airports. The Federal Aviation Administration has