Seth Fletcher in Scientific American:

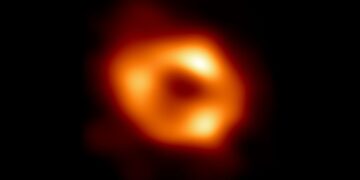

The mystery at the heart of the Milky Way has finally been solved. This morning, at simultaneous press conferences around the world, the astronomers of the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) revealed the first image of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. It’s not the first picture of a black hole this collaboration has given us—that was the iconic image of M87*, which they revealed on April 10, 2019. But it’s the one they wanted most. Sagittarius A* is our own private supermassive black hole, the still point around which our galaxy revolves.

The mystery at the heart of the Milky Way has finally been solved. This morning, at simultaneous press conferences around the world, the astronomers of the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) revealed the first image of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. It’s not the first picture of a black hole this collaboration has given us—that was the iconic image of M87*, which they revealed on April 10, 2019. But it’s the one they wanted most. Sagittarius A* is our own private supermassive black hole, the still point around which our galaxy revolves.

Scientists have long thought that a supermassive black hole hidden deep in the chaotic central region of our galaxy was the only possible explanation for the bizarre things that happen there—such as giant stars slingshotting around an invisible something in space at an appreciable fraction of the speed of light. Yet they’ve been hesitant to say that outright. For example, when astronomers Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez shared a portion of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics for their work on Sagittarius A*, their citation specified that they were awarded for “the discovery of a supermassive compact object at the centre of our galaxy,” not the revelation of a “black hole.” The time for that sort of caution has expired.

More here.

The genre is as old, almost, as the modern novel, and shares its subversive nature. If Don Quixote, among many other things, brought fiction down from the chivalric heights to the pedestrian grounds, so literary biography served as a tonic to the genre of biography as a whole, which has always tended toward the exemplary. James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, considered by many to be the first modern literary biography, details its subject’s appetite for drink, his shabby clothes, his disgusting eating habits. Johnson himself thought it the “business of the biographer to…lead the thoughts into domestic privacies, and display the minute details of daily life.”

The genre is as old, almost, as the modern novel, and shares its subversive nature. If Don Quixote, among many other things, brought fiction down from the chivalric heights to the pedestrian grounds, so literary biography served as a tonic to the genre of biography as a whole, which has always tended toward the exemplary. James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, considered by many to be the first modern literary biography, details its subject’s appetite for drink, his shabby clothes, his disgusting eating habits. Johnson himself thought it the “business of the biographer to…lead the thoughts into domestic privacies, and display the minute details of daily life.” If, in 1979, Rosalind Krauss famously said, “we find it indescribably embarrassing to mention art and spirit in the same sentence,” today many of us find it indescribably embarrassing not to.

If, in 1979, Rosalind Krauss famously said, “we find it indescribably embarrassing to mention art and spirit in the same sentence,” today many of us find it indescribably embarrassing not to. What explains the dramatic progress from 20th-century to 21st-century AI, and how can the remaining limitations of current AI be overcome? The widely accepted narrative attributes this progress to massive increases in the quantity of computational and data resources available to support statistical learning in deep artificial neural networks. We show that an additional crucial factor is the development of a new type of computation. Neurocompositional computing (Smolensky et al., 2022) adopts two principles that must be simultaneously respected to enable human-level cognition: the principles of Compositionality and Continuity. These have seemed irreconcilable until the recent mathematical discovery that compositionality can be realized not only through discrete methods of symbolic computing, but also through novel forms of continuous neural computing. The revolutionary recent progress in AI has resulted from the use of limited forms of neurocompositional computing. New, deeper forms of neurocompositional computing create AI systems that are more robust, accurate,

What explains the dramatic progress from 20th-century to 21st-century AI, and how can the remaining limitations of current AI be overcome? The widely accepted narrative attributes this progress to massive increases in the quantity of computational and data resources available to support statistical learning in deep artificial neural networks. We show that an additional crucial factor is the development of a new type of computation. Neurocompositional computing (Smolensky et al., 2022) adopts two principles that must be simultaneously respected to enable human-level cognition: the principles of Compositionality and Continuity. These have seemed irreconcilable until the recent mathematical discovery that compositionality can be realized not only through discrete methods of symbolic computing, but also through novel forms of continuous neural computing. The revolutionary recent progress in AI has resulted from the use of limited forms of neurocompositional computing. New, deeper forms of neurocompositional computing create AI systems that are more robust, accurate, To say that event A causes event B is to not only make a claim about our actual world, but about other possible worlds — in worlds where A didn’t happen but everything else was the same, B would not have happened. This leads to an obvious difficulty if we want to infer causes from sets of data — we generally only have data about the actual world. Happily, there are ways around this difficulty, and the study of causal relations is of central importance in modern social science and artificial intelligence research. Judea Pearl has been the leader of the “causal revolution,” and we talk about what that means and what questions remain unanswered.

To say that event A causes event B is to not only make a claim about our actual world, but about other possible worlds — in worlds where A didn’t happen but everything else was the same, B would not have happened. This leads to an obvious difficulty if we want to infer causes from sets of data — we generally only have data about the actual world. Happily, there are ways around this difficulty, and the study of causal relations is of central importance in modern social science and artificial intelligence research. Judea Pearl has been the leader of the “causal revolution,” and we talk about what that means and what questions remain unanswered. The departure of Sri Lanka’s prime minister,

The departure of Sri Lanka’s prime minister,  The more affecting terrors in Ghosts include domestic violence, lonely marriages, undignified old age, and suppressed identity. There are disastrous marriages galore: The titular housekeeper of “Mr. Jones” turns out to be the malevolent, long-dead servant who once helped an 18th-century nobleman isolate his deaf and mute wife there. In “The Lady’s Maid’s Bell,” servants come and go; the only constant is the abuse and neglect of the invalid lady of the house by her alcoholic and philandering husband. In “Kerfol,” it turns out that the “most romantic house in Brittany” is haunted not by the sadistic 17th-century aristocrat who owned it but by all the dogs he killed there, pets that had briefly enlivened his wife’s “desolate” and “extremely lonely” life. That backstory is related through the records of a long-ago court case, which diffuses the real-time suspense but does not dull the horrors of that cruel marriage.

The more affecting terrors in Ghosts include domestic violence, lonely marriages, undignified old age, and suppressed identity. There are disastrous marriages galore: The titular housekeeper of “Mr. Jones” turns out to be the malevolent, long-dead servant who once helped an 18th-century nobleman isolate his deaf and mute wife there. In “The Lady’s Maid’s Bell,” servants come and go; the only constant is the abuse and neglect of the invalid lady of the house by her alcoholic and philandering husband. In “Kerfol,” it turns out that the “most romantic house in Brittany” is haunted not by the sadistic 17th-century aristocrat who owned it but by all the dogs he killed there, pets that had briefly enlivened his wife’s “desolate” and “extremely lonely” life. That backstory is related through the records of a long-ago court case, which diffuses the real-time suspense but does not dull the horrors of that cruel marriage. A romantic, and a terrific beauty to boot, Saint Phalle loved love, and men were some of her most potent muses. Elemental to her story is Swiss sculptor Jean Tinguely, who was, over the course of three decades, her lover, her collaborator, her traitor, her ex-lover, and her husband, while remaining throughout her creative interlocutor. “Niki,” she recalled him telling her, “the dream is everything, technique is nothing—you can learn it.” She credited Tinguely for pushing her to realize in the early ’60s her “Tirs” (Shooting Paintings), a series of reliefs made of paint and foodstuffs secreted beneath a plaster surface, works that she would then execute, literally and metaphorically, with a gun. “It was an amazing feeling shooting at a painting and watching it transform itself into a new being,” she wrote of these firebrand performances that brought her to international attention. “It was not only EXCITING and SEXY, but TRAGIC—as though one were witnessing birth and a death at the same moment,” she added, perhaps hearkening back to her own origin story. In the wake of the “Tirs” came the “Nanas,” for which Saint Phalle is best known: enormous, luscious, multicolored sculptures embodying feminine archetypes.

A romantic, and a terrific beauty to boot, Saint Phalle loved love, and men were some of her most potent muses. Elemental to her story is Swiss sculptor Jean Tinguely, who was, over the course of three decades, her lover, her collaborator, her traitor, her ex-lover, and her husband, while remaining throughout her creative interlocutor. “Niki,” she recalled him telling her, “the dream is everything, technique is nothing—you can learn it.” She credited Tinguely for pushing her to realize in the early ’60s her “Tirs” (Shooting Paintings), a series of reliefs made of paint and foodstuffs secreted beneath a plaster surface, works that she would then execute, literally and metaphorically, with a gun. “It was an amazing feeling shooting at a painting and watching it transform itself into a new being,” she wrote of these firebrand performances that brought her to international attention. “It was not only EXCITING and SEXY, but TRAGIC—as though one were witnessing birth and a death at the same moment,” she added, perhaps hearkening back to her own origin story. In the wake of the “Tirs” came the “Nanas,” for which Saint Phalle is best known: enormous, luscious, multicolored sculptures embodying feminine archetypes. W

W Scientists have been trying to unravel the mysteries of why memory diminishes with age for decades. Now they have discovered a possible remedy — cerebrospinal fluid from younger brains

Scientists have been trying to unravel the mysteries of why memory diminishes with age for decades. Now they have discovered a possible remedy — cerebrospinal fluid from younger brains In Jennifer Egan’s 2011 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel A Visit From the Goon Squad, “time is a goon.” It is time that steals youthful promise and dashes hopes. Time that makes people unrecognizable to themselves. In it, time derails the life of kleptomaniac Sasha Blake; it disillusions her record producer boss, Bennie Salazar, and diminishes record executive Lou, once so vital to his teenage girlfriend Jocelyn. Music is good, we are told.

In Jennifer Egan’s 2011 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel A Visit From the Goon Squad, “time is a goon.” It is time that steals youthful promise and dashes hopes. Time that makes people unrecognizable to themselves. In it, time derails the life of kleptomaniac Sasha Blake; it disillusions her record producer boss, Bennie Salazar, and diminishes record executive Lou, once so vital to his teenage girlfriend Jocelyn. Music is good, we are told. The greatness of literature lies in its capacity to communicate the experiences and feelings of human beings in all their variety, affording us glimpses of the boundless vastness of humanity. Literature has told us about war, adventure, love, the monotony of everyday life, political intrigues, the life of different social classes, murderers, banal individuals, artists, ecstasy, the mysterious allure of the world. Can it also tell us anything about the real and profound emotions connected with great science?

The greatness of literature lies in its capacity to communicate the experiences and feelings of human beings in all their variety, affording us glimpses of the boundless vastness of humanity. Literature has told us about war, adventure, love, the monotony of everyday life, political intrigues, the life of different social classes, murderers, banal individuals, artists, ecstasy, the mysterious allure of the world. Can it also tell us anything about the real and profound emotions connected with great science? A SELF-PORTRAIT from 1911 shows Suzanne Valadon at work, presumably creating the image before us. Holding a paint-streaked palette, she turns slightly to the right with lips pursed and eyes narrowed, likely scrutinizing her reflection in a mirror beyond the frame. When Valadon made the portrait, at age forty-six, she would have been quite accustomed to holding a pose. Raised by a single mother in Montmartre, heady epicenter of the Parisian avant-garde, she began working as an artist’s model at the age of fifteen, sitting for the likes of Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec, her friend and lover, who nicknamed her “Suzanna” (her real name was Marie-Clémentine) in winking reference to the biblical figure whose beauty tormented older men. Less familiar to the middle-aged Valadon was holding a brush. The self-taught artist didn’t seriously develop her practice until she was in her thirties, when marriage to a wealthy businessman afforded her the necessary time and support; she only began working with oil paints in 1909, the same year she left her conjugal home to take up with André Utter, a friend of her son, Maurice Utrillo, and more than twenty years her junior. Forged in a moment of personal and professional renewal, Self-Portrait declares Valadon’s hard-won status as subject and painter, mistress of her own canvas double. Valadon spent more than a decade watching male artists assess her and pick her apart; now behind the easel, she contemplates herself with shrewd determination.

A SELF-PORTRAIT from 1911 shows Suzanne Valadon at work, presumably creating the image before us. Holding a paint-streaked palette, she turns slightly to the right with lips pursed and eyes narrowed, likely scrutinizing her reflection in a mirror beyond the frame. When Valadon made the portrait, at age forty-six, she would have been quite accustomed to holding a pose. Raised by a single mother in Montmartre, heady epicenter of the Parisian avant-garde, she began working as an artist’s model at the age of fifteen, sitting for the likes of Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec, her friend and lover, who nicknamed her “Suzanna” (her real name was Marie-Clémentine) in winking reference to the biblical figure whose beauty tormented older men. Less familiar to the middle-aged Valadon was holding a brush. The self-taught artist didn’t seriously develop her practice until she was in her thirties, when marriage to a wealthy businessman afforded her the necessary time and support; she only began working with oil paints in 1909, the same year she left her conjugal home to take up with André Utter, a friend of her son, Maurice Utrillo, and more than twenty years her junior. Forged in a moment of personal and professional renewal, Self-Portrait declares Valadon’s hard-won status as subject and painter, mistress of her own canvas double. Valadon spent more than a decade watching male artists assess her and pick her apart; now behind the easel, she contemplates herself with shrewd determination. Here we go again. Nearly six months after researchers in South Africa identified the Omicron coronavirus variant, two offshoots of the game-changing lineage are once again driving a surge in COVID-19 cases there.

Here we go again. Nearly six months after researchers in South Africa identified the Omicron coronavirus variant, two offshoots of the game-changing lineage are once again driving a surge in COVID-19 cases there.