Seth Stephens-Davidowitz in The New York Times:

We now know who is rich in America. And it’s not who you might have guessed. A groundbreaking 2019 study by four economists, “Capitalists in the Twenty-First Century,” analyzed de-identified data of the complete universe of American taxpayers to determine who dominated the top 0.1 percent of earners. The study didn’t tell us about the small number of well-known tech and shopping billionaires but instead about the more than 140,000 Americans who earn more than $1.58 million per year. The researchers found that the typical rich American is, in their words, the owner of a “regional business,” such as an “auto dealer” or a “beverage distributor.”

We now know who is rich in America. And it’s not who you might have guessed. A groundbreaking 2019 study by four economists, “Capitalists in the Twenty-First Century,” analyzed de-identified data of the complete universe of American taxpayers to determine who dominated the top 0.1 percent of earners. The study didn’t tell us about the small number of well-known tech and shopping billionaires but instead about the more than 140,000 Americans who earn more than $1.58 million per year. The researchers found that the typical rich American is, in their words, the owner of a “regional business,” such as an “auto dealer” or a “beverage distributor.”

…The most important happiness study, in my opinion, is the Mappiness project, founded by the British economists Susana Mourato and George MacKerron. The researchers pinged tens of thousands of people on their smartphones and asked them simple questions: Who are they with? What are they doing? How happy are they? From this, they built a sample of more than three million data points, orders of magnitude more than previous studies on happiness. So what do three million happiness data points tell us?

More here.

N

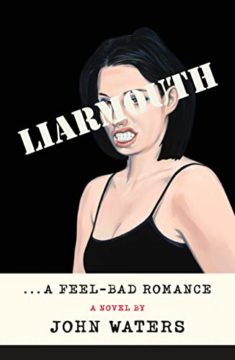

N What you get from John Waters is crotch punching, exploding televisions, geysers of blood, deviants, wackos and reprobates. You get phrases like “ridiculous genital display” and “penis probation”; scatology, tickle fetishes and satanic babies. You get teeming panoramas of freaks in thrall to their own depravity. (Another painter comes to mind: Hieronymus Bosch.)

What you get from John Waters is crotch punching, exploding televisions, geysers of blood, deviants, wackos and reprobates. You get phrases like “ridiculous genital display” and “penis probation”; scatology, tickle fetishes and satanic babies. You get teeming panoramas of freaks in thrall to their own depravity. (Another painter comes to mind: Hieronymus Bosch.) Sam Anderson in the New York Times:

Sam Anderson in the New York Times: Ryan Ruby in The New Left Review’s Sidecar:

Ryan Ruby in The New Left Review’s Sidecar: Patrick J. Deneen over at his substack The Postliberal Order (photo by Matt Cashore/University of Notre Dame):

Patrick J. Deneen over at his substack The Postliberal Order (photo by Matt Cashore/University of Notre Dame): Suzanne Cope in Aeon:

Suzanne Cope in Aeon:

One of the recent trends on TikTok is an aesthetic called “night luxe.” It embodies the kind of performative opulence one usually encounters at New Year’s Eve parties: champagne, disco balls, bedazzled accessories, and golden sparkles. “Night luxe” doesn’t actually mean anything. It isn’t a

One of the recent trends on TikTok is an aesthetic called “night luxe.” It embodies the kind of performative opulence one usually encounters at New Year’s Eve parties: champagne, disco balls, bedazzled accessories, and golden sparkles. “Night luxe” doesn’t actually mean anything. It isn’t a  In the early years of the 1980s, I was fooling around with a novel that explored a future in which the United States had become disunited. Part of it had turned into a theocratic dictatorship based on 17th-century New England Puritan religious tenets and jurisprudence. I set this novel in and around Harvard University—an institution that in the 1980s was renowned for its liberalism, but that had begun three centuries earlier chiefly as a training college for Puritan clergy.

In the early years of the 1980s, I was fooling around with a novel that explored a future in which the United States had become disunited. Part of it had turned into a theocratic dictatorship based on 17th-century New England Puritan religious tenets and jurisprudence. I set this novel in and around Harvard University—an institution that in the 1980s was renowned for its liberalism, but that had begun three centuries earlier chiefly as a training college for Puritan clergy.

While living in an internment camp in Vichy France, Alexander Grothendieck was tutored in mathematics by another prisoner, a girl named Maria. Maria taught Grothendieck, who was twelve, the definition of a circle: all the points that are equidistant from a given point. The definition impressed him with “its simplicity and clarity,” he wrote years later. The property of perfect rotundity had until then appeared to him to be “mysterious beyond words.”

While living in an internment camp in Vichy France, Alexander Grothendieck was tutored in mathematics by another prisoner, a girl named Maria. Maria taught Grothendieck, who was twelve, the definition of a circle: all the points that are equidistant from a given point. The definition impressed him with “its simplicity and clarity,” he wrote years later. The property of perfect rotundity had until then appeared to him to be “mysterious beyond words.” Though the 1973 decision in Roe established a constitutionally protected right to abortion, it never guaranteed abortion access. The Supreme Court held only that state criminal laws banning abortion were an infringement of the constitutional right to privacy. Patients, in consultation with their physicians, could elect to have an abortion for any reason during the first trimester of pregnancy. In the second trimester states could regulate abortions in order to protect the pregnant person’s health or the dignity of potential life, but after the second trimester, a state was permitted to ban abortion unless terminating the pregnancy was necessary to preserve the patient’s life or health. This trimester system was abandoned in 1992, when the Court held that states could restrict abortion before viability—around twenty-four weeks of gestation—so long as the regulation did not place a “substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a nonviable fetus.” The Court’s decision to reject Roe’s trimester framework nevertheless claimed to preserve “the essential holding of Roe.”

Though the 1973 decision in Roe established a constitutionally protected right to abortion, it never guaranteed abortion access. The Supreme Court held only that state criminal laws banning abortion were an infringement of the constitutional right to privacy. Patients, in consultation with their physicians, could elect to have an abortion for any reason during the first trimester of pregnancy. In the second trimester states could regulate abortions in order to protect the pregnant person’s health or the dignity of potential life, but after the second trimester, a state was permitted to ban abortion unless terminating the pregnancy was necessary to preserve the patient’s life or health. This trimester system was abandoned in 1992, when the Court held that states could restrict abortion before viability—around twenty-four weeks of gestation—so long as the regulation did not place a “substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a nonviable fetus.” The Court’s decision to reject Roe’s trimester framework nevertheless claimed to preserve “the essential holding of Roe.” I am a university professor. I make my living teaching and doing research at a liberal arts school in Southern California. Last year, I took a brave step: I decided to become a student and signed up for online Arabic classes. I joined an online language course offered by a company based in Cairo. Full disclosure: This was my third attempt at learning Arabic over the past 10 years. Arabic is a notoriously hard language, given its expansive vocabulary. A Moroccan feminist scholar told me once that there are 50 words for “love” in Arabic – a fascinating and intimidating fact. My earlier attempts at mastering synonyms had proved her right.

I am a university professor. I make my living teaching and doing research at a liberal arts school in Southern California. Last year, I took a brave step: I decided to become a student and signed up for online Arabic classes. I joined an online language course offered by a company based in Cairo. Full disclosure: This was my third attempt at learning Arabic over the past 10 years. Arabic is a notoriously hard language, given its expansive vocabulary. A Moroccan feminist scholar told me once that there are 50 words for “love” in Arabic – a fascinating and intimidating fact. My earlier attempts at mastering synonyms had proved her right.