Eyal Press in Public Books:

Ta-Nehisi Coates is best known for his writing about racism in America—in particular, his 2014 essay “The Case for Reparations,” and his 2015 book, Between the World and Me. Ta-Nehisi’s readers know that the toll racism has inflicted on the bodies of Black people, and the enduring power of white supremacy, have long preoccupied him. On this show, however, he’ll be talking about a subject—or rather an influence—that few people associate with his work.

Ta-Nehisi Coates is best known for his writing about racism in America—in particular, his 2014 essay “The Case for Reparations,” and his 2015 book, Between the World and Me. Ta-Nehisi’s readers know that the toll racism has inflicted on the bodies of Black people, and the enduring power of white supremacy, have long preoccupied him. On this show, however, he’ll be talking about a subject—or rather an influence—that few people associate with his work.

That influence is the late Tony Judt, a British historian. In 2005, Judt published his magnum opus, Postwar, a sweeping, 933-page history of modern Europe.

In this conversation, which was recorded last fall, Ta-Nehisi talks about why Postwar had such a profound impact on him. He explores the preface he wrote to Ill Fares the Land, another of Judt’s books, which has just been reissued by Penguin. He also talks about the power of language to help us imagine a better world, whether he identifies as an Afro-pessimist, and what it’s like to grow up in a nationalist household.

From here.

Throughout Il Buco, most human speech—apart from that in a television feature on the Pirelli palace and the old man’s cattle calls—is only ever heard at a distance, both standard Italian and Calabrian dialects disappearing into the acoustic fabric of the film. Cinematographer Renato Berta’s camera, either suffocatingly close or slightly afield from its subjects, hastens this sensorial defamiliarization. So does the rarity of subtitles. That these only appear under two brief archival segments—the aforementioned scientific report and the Pirelli doc, viewed, in a beguiling crepuscular scene, by a mesmerized group of townspeople motionlessly watching a television plopped outside on the dirt—is to insist upon a certain incommunicability. Despite our best efforts to dominate the heavens and the underworld, some places evade epistemic capture. Murmurous soundscapes, both infinitesimal and grandiose, perplex and disorient, causing human agents and their endeavors to appear more like incidental elements in the greater chasm of time.

Throughout Il Buco, most human speech—apart from that in a television feature on the Pirelli palace and the old man’s cattle calls—is only ever heard at a distance, both standard Italian and Calabrian dialects disappearing into the acoustic fabric of the film. Cinematographer Renato Berta’s camera, either suffocatingly close or slightly afield from its subjects, hastens this sensorial defamiliarization. So does the rarity of subtitles. That these only appear under two brief archival segments—the aforementioned scientific report and the Pirelli doc, viewed, in a beguiling crepuscular scene, by a mesmerized group of townspeople motionlessly watching a television plopped outside on the dirt—is to insist upon a certain incommunicability. Despite our best efforts to dominate the heavens and the underworld, some places evade epistemic capture. Murmurous soundscapes, both infinitesimal and grandiose, perplex and disorient, causing human agents and their endeavors to appear more like incidental elements in the greater chasm of time. Jean-Luc Marion (b. 1946) and Chantal Delsol (b. 1947) are both prominent French philosophers who are very public about their Roman Catholicism. This alone would put them, in the minds of many of their fellow citizens, into “conservative” political and cultural camps, though the truth is considerably more complicated. This past year saw the appearance in English translation of Marion’s 2017 book,

Jean-Luc Marion (b. 1946) and Chantal Delsol (b. 1947) are both prominent French philosophers who are very public about their Roman Catholicism. This alone would put them, in the minds of many of their fellow citizens, into “conservative” political and cultural camps, though the truth is considerably more complicated. This past year saw the appearance in English translation of Marion’s 2017 book,  NOT ALL THAT LONG AGO,

NOT ALL THAT LONG AGO, In 1914, when World War I broke out, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the most influential neuroscientist in the world—the man who discovered brain cells, later termed neurons— published only one article, by far his lowest output ever. “The horrendous European war of 1914 was for my scientific activity a very rude blow,” Cajal recalled. “It altered my health, already somewhat disturbed, and it cooled, for the first time, my enthusiasm for investigation.” Cajal’s tertulia, or café social circle, was “overwhelmed with horror and abomination, erasing the last relics of our youthful optimism.” Science was supposed to be universal, but now, as mail became unreliable, telegraph lines were cut, trenches were dug, and borders were almost constantly closed, scientists could not even share their work internationally.

In 1914, when World War I broke out, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the most influential neuroscientist in the world—the man who discovered brain cells, later termed neurons— published only one article, by far his lowest output ever. “The horrendous European war of 1914 was for my scientific activity a very rude blow,” Cajal recalled. “It altered my health, already somewhat disturbed, and it cooled, for the first time, my enthusiasm for investigation.” Cajal’s tertulia, or café social circle, was “overwhelmed with horror and abomination, erasing the last relics of our youthful optimism.” Science was supposed to be universal, but now, as mail became unreliable, telegraph lines were cut, trenches were dug, and borders were almost constantly closed, scientists could not even share their work internationally. When his first novel,

When his first novel, For many decades, part of the premise behind AI was that artificial intelligence should take inspiration from natural intelligence. John McCarthy, one of the co-founders of AI, wrote groundbreaking papers on

For many decades, part of the premise behind AI was that artificial intelligence should take inspiration from natural intelligence. John McCarthy, one of the co-founders of AI, wrote groundbreaking papers on  I am trying, in reviewing Why We Are Restless, an excellent new book by Benjamin Storey and Jenna Silber Storey, to keep myself out of it. My usual essayistic approach, I fear, will lead a reader to think that I object to the book’s diagnosis of what went wrong with the modern world more than I do. Besides, the tendency of critics to involve themselves in their reviews is irritating, and surely an example of the type of Montaignean introspection that may well be making us restless. But Why We Are Restless stands out among other books like it by answering the question implied by its title with rigor and charity, by (mostly) succeeding in presenting the view it contests “in terms of the most decent human aspirations.” Cataloguing one’s own restlessness, or subjecting readers to one’s bargain-bin Tocquevillian observations about the United States of America, would veer dangerously into the Montaignean territory here scrutinized. I will make an attempt (essai), in other words, to share some thoughts (pensées) about this fine book.

I am trying, in reviewing Why We Are Restless, an excellent new book by Benjamin Storey and Jenna Silber Storey, to keep myself out of it. My usual essayistic approach, I fear, will lead a reader to think that I object to the book’s diagnosis of what went wrong with the modern world more than I do. Besides, the tendency of critics to involve themselves in their reviews is irritating, and surely an example of the type of Montaignean introspection that may well be making us restless. But Why We Are Restless stands out among other books like it by answering the question implied by its title with rigor and charity, by (mostly) succeeding in presenting the view it contests “in terms of the most decent human aspirations.” Cataloguing one’s own restlessness, or subjecting readers to one’s bargain-bin Tocquevillian observations about the United States of America, would veer dangerously into the Montaignean territory here scrutinized. I will make an attempt (essai), in other words, to share some thoughts (pensées) about this fine book. W

W Are you an “insider threat?”

Are you an “insider threat?” When I want to know what the future is going to be like, I go ask

When I want to know what the future is going to be like, I go ask  Last summer, three researchers took a small step toward answering one of the most important questions in theoretical computer science. To

Last summer, three researchers took a small step toward answering one of the most important questions in theoretical computer science. To  The upside of many NFTs having a uniform visual style is that, theoretically, as many of the medium’s biggest fans will stress, there is something inherently democratic about their design and their acquisition. If not every NFT creator makes the kind of money Bored Ape Yacht Club makes, they still have a fairly equal opportunity to share their work. Searching OpenSea for pieces is still easier by far than buying physical work from a gallery or an auction, and the only barrier to entry is a working knowledge of cryptocurrency. Buyers and artists who grew up on the internet of the 00s, meanwhile, may experience deja vu when given the opportunity to customise what is effectively an avatar, harking back to online cartoons like Blingees or Dollz Mania. When a rash of articles appeared in 2021 suggesting NFTs might be the Beanie Babies of the 2020s, the comparison was meant to be an insult; still, it is hard to overestimate the power of nostalgia when it comes to millennials on the web.

The upside of many NFTs having a uniform visual style is that, theoretically, as many of the medium’s biggest fans will stress, there is something inherently democratic about their design and their acquisition. If not every NFT creator makes the kind of money Bored Ape Yacht Club makes, they still have a fairly equal opportunity to share their work. Searching OpenSea for pieces is still easier by far than buying physical work from a gallery or an auction, and the only barrier to entry is a working knowledge of cryptocurrency. Buyers and artists who grew up on the internet of the 00s, meanwhile, may experience deja vu when given the opportunity to customise what is effectively an avatar, harking back to online cartoons like Blingees or Dollz Mania. When a rash of articles appeared in 2021 suggesting NFTs might be the Beanie Babies of the 2020s, the comparison was meant to be an insult; still, it is hard to overestimate the power of nostalgia when it comes to millennials on the web. During his lifetime, there was a long line of people who thought Admiral Hyman Rickover was an insufferable son of a bitch, a contemptible ass, an overbearing, opinionated, power-hungry menace. Biographer Marc Wortman called him, “obstinate, egotistical, and abrasive…” (119)

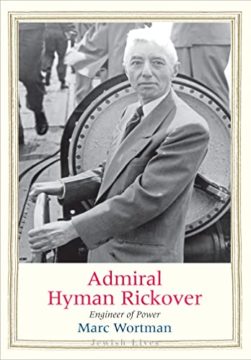

During his lifetime, there was a long line of people who thought Admiral Hyman Rickover was an insufferable son of a bitch, a contemptible ass, an overbearing, opinionated, power-hungry menace. Biographer Marc Wortman called him, “obstinate, egotistical, and abrasive…” (119) It was at a party in Greenwich Village, in the spring of 1920, that the critic Edmund Wilson first encountered

It was at a party in Greenwich Village, in the spring of 1920, that the critic Edmund Wilson first encountered