When All the Others Were Away at Mass

When all the others were away at Mass

I was all hers as we peeled potatoes.

They broke the silence, let fall one by one

Like solder weeping off the soldering iron:

Cold comforts set between us, things to share

Gleaming in a bucket of clean water.

And again let fall. Little pleasant splashes

From each other’s work would bring us to our senses.

So while the parish priest at her bedside

Went hammer and tongs at the prayers for the dying

And some were responding and some crying

I remembered her head bent towards my head,

Her breath in mine, our fluent dipping knives–

Never closer the whole rest of our lives.

by Seamus Heaney

from Clearances in Memorium, 1911-1984

Faber and Faber, 1987

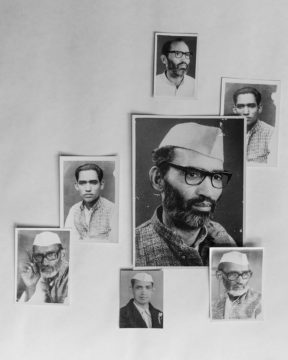

There is a particular collage in Indian photographer Devashish Gaur’s project This Is The Closest We Will Get that stands out in its cut-and-paste simplicity. Entitled Me and Dad, it’s a portrait, black and white, cropped at the shoulders, but most importantly, it depicts two men instead of one. The sitter of the original photograph—an archival one that’s been collaged over—wears a checkered suit and his hair is neatly swept to the side. It feels formal, perhaps a little dated even. Meanwhile, slices of a second face, arranged over this sitter, belong to his son—the photographer, Gaur himself. And their features, the contours and outlines of their faces, do seem to blend quite remarkably. Father and boy, artist and sitter, portrait and self-portrait, entwined.

There is a particular collage in Indian photographer Devashish Gaur’s project This Is The Closest We Will Get that stands out in its cut-and-paste simplicity. Entitled Me and Dad, it’s a portrait, black and white, cropped at the shoulders, but most importantly, it depicts two men instead of one. The sitter of the original photograph—an archival one that’s been collaged over—wears a checkered suit and his hair is neatly swept to the side. It feels formal, perhaps a little dated even. Meanwhile, slices of a second face, arranged over this sitter, belong to his son—the photographer, Gaur himself. And their features, the contours and outlines of their faces, do seem to blend quite remarkably. Father and boy, artist and sitter, portrait and self-portrait, entwined. As a mother of six and a Mormon, I have a good understanding of arguments surrounding abortion, religious and otherwise. When I hear men discussing women’s reproductive rights, I’m often left with the thought that they have zero interest in stopping abortion. If you want to prevent abortion, you need to prevent unwanted pregnancies. Men seem unable (or unwilling) to admit that they cause 100% of them. I realize that’s a bold statement. You’re likely thinking, “Wait. It takes two to tango!” While I fully agree with you in the case of intentional pregnancies, I argue that all unwanted pregnancies are caused by the irresponsible ejaculations of men. All of them.

As a mother of six and a Mormon, I have a good understanding of arguments surrounding abortion, religious and otherwise. When I hear men discussing women’s reproductive rights, I’m often left with the thought that they have zero interest in stopping abortion. If you want to prevent abortion, you need to prevent unwanted pregnancies. Men seem unable (or unwilling) to admit that they cause 100% of them. I realize that’s a bold statement. You’re likely thinking, “Wait. It takes two to tango!” While I fully agree with you in the case of intentional pregnancies, I argue that all unwanted pregnancies are caused by the irresponsible ejaculations of men. All of them. S

S The nature of time. Black holes. Ancient philosophers. The struggle for democracy. Climate change. Buddhist philosophy. In his new collection of essays and articles, Carlo Rovelli, one of the world’s most renowned physicists, broadens his writing to include questions of politics, justice and how we live now.

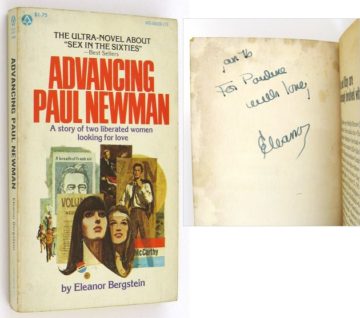

The nature of time. Black holes. Ancient philosophers. The struggle for democracy. Climate change. Buddhist philosophy. In his new collection of essays and articles, Carlo Rovelli, one of the world’s most renowned physicists, broadens his writing to include questions of politics, justice and how we live now. I became aware of Advancing Paul Newman, Eleanor Bergstein’s 1973 debut novel, through Anatole Broyard’s dismissive review, which I came across in some undirected archival wandering. His grating condescension spurred me to read the novel—one of the best minor rebellions I’ve ever undertaken. (Bergstein is best known for writing the movie Dirty Dancing.) “This is the story of two girls, each of whom suspected the other of a more passionate connection with life,” she writes of the protagonists, best friends Kitsy and Ila. The romance of their friendship holds together everything else: trips to Europe to collect experiences (which, of course, often disappoint), becoming or failing to become writers, love affairs and marriages and divorces, their idealistic campaigning for the anti-war presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy in 1968. But Advancing Paul Newman is not simply a story of friendship, albeit one between two complicated women. The book is also gorgeously deranged and witty, told in fragments and leaps. “Don’t find me poignant, you ass,” Kitsy snaps at her ex when he happens upon her eating alone in a restaurant. After bad sex in Italy, she says matter-of-factly, “This was a good experience because now I know what it feels like to have my flesh crawl.” Ila is “glorious when in love, undistinguished when not in love,” and sleeps with two men on the day of Kitsy’s wedding. “There were reasons.”

I became aware of Advancing Paul Newman, Eleanor Bergstein’s 1973 debut novel, through Anatole Broyard’s dismissive review, which I came across in some undirected archival wandering. His grating condescension spurred me to read the novel—one of the best minor rebellions I’ve ever undertaken. (Bergstein is best known for writing the movie Dirty Dancing.) “This is the story of two girls, each of whom suspected the other of a more passionate connection with life,” she writes of the protagonists, best friends Kitsy and Ila. The romance of their friendship holds together everything else: trips to Europe to collect experiences (which, of course, often disappoint), becoming or failing to become writers, love affairs and marriages and divorces, their idealistic campaigning for the anti-war presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy in 1968. But Advancing Paul Newman is not simply a story of friendship, albeit one between two complicated women. The book is also gorgeously deranged and witty, told in fragments and leaps. “Don’t find me poignant, you ass,” Kitsy snaps at her ex when he happens upon her eating alone in a restaurant. After bad sex in Italy, she says matter-of-factly, “This was a good experience because now I know what it feels like to have my flesh crawl.” Ila is “glorious when in love, undistinguished when not in love,” and sleeps with two men on the day of Kitsy’s wedding. “There were reasons.” In February 2020, with COVID-19 spreading rapidly around the globe and antigen tests hard to come by, some physicians turned to artificial intelligence (AI) to try to diagnose cases

In February 2020, with COVID-19 spreading rapidly around the globe and antigen tests hard to come by, some physicians turned to artificial intelligence (AI) to try to diagnose cases Trained on billions of words from books, news articles, and Wikipedia, artificial intelligence (AI) language models can produce uncannily human prose. They can generate tweets, summarize emails, and translate dozens of languages. They can even write tolerable poetry. And like overachieving students, they quickly master the tests, called benchmarks, that computer scientists devise for them. That was Sam Bowman’s sobering experience when he and his colleagues created a tough new benchmark for language models called GLUE (General Language Understanding Evaluation). GLUE gives AI models the chance to train on data sets containing thousands of sentences and confronts them with nine tasks, such as deciding whether a test sentence is grammatical, assessing its sentiment, or judging whether one sentence logically entails another. After completing the tasks, each model is given an average score.

Trained on billions of words from books, news articles, and Wikipedia, artificial intelligence (AI) language models can produce uncannily human prose. They can generate tweets, summarize emails, and translate dozens of languages. They can even write tolerable poetry. And like overachieving students, they quickly master the tests, called benchmarks, that computer scientists devise for them. That was Sam Bowman’s sobering experience when he and his colleagues created a tough new benchmark for language models called GLUE (General Language Understanding Evaluation). GLUE gives AI models the chance to train on data sets containing thousands of sentences and confronts them with nine tasks, such as deciding whether a test sentence is grammatical, assessing its sentiment, or judging whether one sentence logically entails another. After completing the tasks, each model is given an average score. Last week, Ken Roth, who’s led Human Rights Watch for nearly 30 years, announced that he was stepping down. Over the course of his career, Roth, a former U.S. federal prosecutor, has had a profound impact on the organization and the cause he serves. What was once a modest outfit of some 60 people with a budget of $7 million is now a major global operation of 552 staffers operating in more than 100 countries and with a budget of close to $100 million. But Roth’s tenure hasn’t just been about organization-building or fundraising. In the course of his years with Human Rights Watch, he’s met with dozens of heads of state and worked in more than 50 countries. Under his management, the group shared the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize for working to ban landmines; helped the UN establish the war crimes tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, and then the International Criminal Court; and fought against the use of cluster munitions and child soldiers, among many issues. Along the way, as you’d expect, Roth has made many friends and supporters but also enemies; at various moments, he’s been accused of anti-Semitism (despite being Jewish), been attacked by Republican politicians in the United States, and has been denounced by a long list of autocratic governments, from China to Rwanda. I’ve known Roth for many years and was curious to get his reflections on a career spent fighting for justice, as well as the state of the world today and how it compares to 1993, when he was first named executive director of Human Rights Watch. We spoke about all this and more on Tuesday.

Last week, Ken Roth, who’s led Human Rights Watch for nearly 30 years, announced that he was stepping down. Over the course of his career, Roth, a former U.S. federal prosecutor, has had a profound impact on the organization and the cause he serves. What was once a modest outfit of some 60 people with a budget of $7 million is now a major global operation of 552 staffers operating in more than 100 countries and with a budget of close to $100 million. But Roth’s tenure hasn’t just been about organization-building or fundraising. In the course of his years with Human Rights Watch, he’s met with dozens of heads of state and worked in more than 50 countries. Under his management, the group shared the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize for working to ban landmines; helped the UN establish the war crimes tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, and then the International Criminal Court; and fought against the use of cluster munitions and child soldiers, among many issues. Along the way, as you’d expect, Roth has made many friends and supporters but also enemies; at various moments, he’s been accused of anti-Semitism (despite being Jewish), been attacked by Republican politicians in the United States, and has been denounced by a long list of autocratic governments, from China to Rwanda. I’ve known Roth for many years and was curious to get his reflections on a career spent fighting for justice, as well as the state of the world today and how it compares to 1993, when he was first named executive director of Human Rights Watch. We spoke about all this and more on Tuesday.

The first tank hadn’t yet rolled across the border before the

The first tank hadn’t yet rolled across the border before the  T

T Today almost as many Caribbeans reside overseas than live at home. Outward and inward migration from and to the region provides an illuminating case study into the pattern and history of migration. Immigrant has become a dirty word, a term of abuse. But Caribbean pioneers have been, and continue to be, a great expeditionary force that keeps the world turning.

Today almost as many Caribbeans reside overseas than live at home. Outward and inward migration from and to the region provides an illuminating case study into the pattern and history of migration. Immigrant has become a dirty word, a term of abuse. But Caribbean pioneers have been, and continue to be, a great expeditionary force that keeps the world turning.