Trevor Quirk in Guernica:

For the millions who were enraged, disgusted, and shocked by the Capitol riots of January 6, the enduring object of skepticism has been not so much the lie that provoked the riots but the believers themselves. A year out, and book publishers confirmed this, releasing titles that addressed the question still addling public consciousness: How can people believe this shit? A minority of rioters at the Capitol had nefarious intentions rooted in authentic ideology, but most of them conveyed no purpose other than to announce to the world that they believed — specifically, that the 2020 election was hijacked through an international conspiracy — and that nothing could sway their confidence. This belief possessed them, not the other way around.

For the millions who were enraged, disgusted, and shocked by the Capitol riots of January 6, the enduring object of skepticism has been not so much the lie that provoked the riots but the believers themselves. A year out, and book publishers confirmed this, releasing titles that addressed the question still addling public consciousness: How can people believe this shit? A minority of rioters at the Capitol had nefarious intentions rooted in authentic ideology, but most of them conveyed no purpose other than to announce to the world that they believed — specifically, that the 2020 election was hijacked through an international conspiracy — and that nothing could sway their confidence. This belief possessed them, not the other way around.

At first, I’d found the riots both terrifying and darkly hilarious, but those sentiments were soon overwon by a strange exasperation that has persisted ever since. It’s a feeling that has robbed me of my capacity to laugh at conspiracy theories — QAnon, chemtrails, lizardmen, whatever — and the people who espouse them. My exasperation is for lack of an explanation.

More here.

A major reason why new vaccines are important – and why the world is still dealing with COVID-19 – is the continued emergence of

A major reason why new vaccines are important – and why the world is still dealing with COVID-19 – is the continued emergence of  Concern about the proliferation of hate speech motivates many who oppose the recent acquisition of Twitter by billionaire Elon Musk, who says he plans to turn the

Concern about the proliferation of hate speech motivates many who oppose the recent acquisition of Twitter by billionaire Elon Musk, who says he plans to turn the  The Court Chamber inside the Pantheon-like building of the Supreme Court of the United States is adorned with marble friezes depicting ancient lawgivers, including Hammurabi, Moses, and Confucius. To begin each session of the Court, at ten o’clock in the morning, the marshal strikes a gavel and commands, “All rise!” The audience goes silent and obeys. The nine Justices, in dark robes, then emerge from behind a heavy velvet curtain to take their seats on the elevated mahogany bench, as the marshal announces, “The Honorable, the Chief Justice and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. Oyez! Oyez! Oyez! All persons having business before the Honorable, the Supreme Court of the United States, are admonished to draw near and give their attention, for the Court is now sitting. God save the United States and this Honorable Court!” It is the closest thing we have, in the American civic sphere, to a papal audience.

The Court Chamber inside the Pantheon-like building of the Supreme Court of the United States is adorned with marble friezes depicting ancient lawgivers, including Hammurabi, Moses, and Confucius. To begin each session of the Court, at ten o’clock in the morning, the marshal strikes a gavel and commands, “All rise!” The audience goes silent and obeys. The nine Justices, in dark robes, then emerge from behind a heavy velvet curtain to take their seats on the elevated mahogany bench, as the marshal announces, “The Honorable, the Chief Justice and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. Oyez! Oyez! Oyez! All persons having business before the Honorable, the Supreme Court of the United States, are admonished to draw near and give their attention, for the Court is now sitting. God save the United States and this Honorable Court!” It is the closest thing we have, in the American civic sphere, to a papal audience. Two events occurred Monday night — one historic, the other rather insignificant — which placed an unflattering spotlight on the Supreme Court of the United States. The historic event was that Politico published an unprecedented leak of a draft majority opinion, by Justice Samuel Alito, which would

Two events occurred Monday night — one historic, the other rather insignificant — which placed an unflattering spotlight on the Supreme Court of the United States. The historic event was that Politico published an unprecedented leak of a draft majority opinion, by Justice Samuel Alito, which would  Russian impresario, Sergei Diaghilev, trained his spyglass on modernism, plotless ballets of pure motion with cubist sets and minimal costumes, but he also knew box office when he saw it, and because his Ballets Russes was a touring company that never performed in the country for which it was named, he also presented fantastic ballets that audiences loved, happy to be cast under the spell of Scheherazade, the Firebird, Giselle. Diaghilev, always ready to go overboard, staged a version of The Sleeping Princess with huge trompe l’oeil sets and over three hundred costumes. Courtiers and princes wore jewelled plumed turbans, ladies of the court were dressed in ornate gowns with trains and capes and gold-buckled shoes. The evil Carabosse had bony arms that ended in claws, a long haphazardly leopard-spotted cloak, conical hat, and in silhouette, she looked like a rat. Critics called the productions a gorgeous calamity. In London, in 1921, it wasn’t Aurora, Keynes fell in love with, but the Lilac Fairy, the creature who put the kingdom to sleep, so as to delay the effects of the jilted fairy’s curse. The Lilac Fairy was danced by Lydia Lopokova, and when attendance fell off, he made sure to sit in empty box where she would notice him.

Russian impresario, Sergei Diaghilev, trained his spyglass on modernism, plotless ballets of pure motion with cubist sets and minimal costumes, but he also knew box office when he saw it, and because his Ballets Russes was a touring company that never performed in the country for which it was named, he also presented fantastic ballets that audiences loved, happy to be cast under the spell of Scheherazade, the Firebird, Giselle. Diaghilev, always ready to go overboard, staged a version of The Sleeping Princess with huge trompe l’oeil sets and over three hundred costumes. Courtiers and princes wore jewelled plumed turbans, ladies of the court were dressed in ornate gowns with trains and capes and gold-buckled shoes. The evil Carabosse had bony arms that ended in claws, a long haphazardly leopard-spotted cloak, conical hat, and in silhouette, she looked like a rat. Critics called the productions a gorgeous calamity. In London, in 1921, it wasn’t Aurora, Keynes fell in love with, but the Lilac Fairy, the creature who put the kingdom to sleep, so as to delay the effects of the jilted fairy’s curse. The Lilac Fairy was danced by Lydia Lopokova, and when attendance fell off, he made sure to sit in empty box where she would notice him. I have a story in my book about Greenberg that relates to this idea of charms and to formalism. In his book Sade, Fourier, Loyola (1971), Barthes talks about the style of a great writer as the writer’s “charm.” Once, after Greenberg had died, I was asked to be part of a panel at Harvard University in honor of the 80th anniversary of Greenberg’s birth. Heading to Boston on the train I thought, “I can’t be part of this panel celebrating Greenberg and trash him.” I had trashed him, for instance, in The Optical Unconscious — the last part about Jackson Pollock was meant to demolish Greenberg. So, I asked myself, what can I say about Greenberg at Harvard that won’t be hypocritical but will be positive? Then I thought about Barthes’s notion of charm.

I have a story in my book about Greenberg that relates to this idea of charms and to formalism. In his book Sade, Fourier, Loyola (1971), Barthes talks about the style of a great writer as the writer’s “charm.” Once, after Greenberg had died, I was asked to be part of a panel at Harvard University in honor of the 80th anniversary of Greenberg’s birth. Heading to Boston on the train I thought, “I can’t be part of this panel celebrating Greenberg and trash him.” I had trashed him, for instance, in The Optical Unconscious — the last part about Jackson Pollock was meant to demolish Greenberg. So, I asked myself, what can I say about Greenberg at Harvard that won’t be hypocritical but will be positive? Then I thought about Barthes’s notion of charm. Why is the Anglo-Saxon world so individualistic, and why has China leaned towards collectivism? Was it Adam Smith, or the Bill of Rights; communism and Mao? According to at least one economist, there might be an altogether more surprising explanation: the difference between wheat and rice. You see, it’s fairly straightforward for a lone farmer to sow wheat in soil and live off the harvest. Rice is a different affair: it requires extensive irrigation, which means cooperation across parcels of land, even centralised planning. A place where wheat grows favours the entrepreneur; a place where rice grows favours the bureaucrat.

Why is the Anglo-Saxon world so individualistic, and why has China leaned towards collectivism? Was it Adam Smith, or the Bill of Rights; communism and Mao? According to at least one economist, there might be an altogether more surprising explanation: the difference between wheat and rice. You see, it’s fairly straightforward for a lone farmer to sow wheat in soil and live off the harvest. Rice is a different affair: it requires extensive irrigation, which means cooperation across parcels of land, even centralised planning. A place where wheat grows favours the entrepreneur; a place where rice grows favours the bureaucrat. Evolution has equipped species with a variety of ways to travel through the air — flapping, gliding, floating, not to mention jumping really high. But it hasn’t invented jet engines. What are the different ways that heavier-than-air objects might be made to fly, and why does natural selection produce some of them but not others? Richard Dawkins has a new book on the subject,

Evolution has equipped species with a variety of ways to travel through the air — flapping, gliding, floating, not to mention jumping really high. But it hasn’t invented jet engines. What are the different ways that heavier-than-air objects might be made to fly, and why does natural selection produce some of them but not others? Richard Dawkins has a new book on the subject,  Among the many

Among the many  Theologians sometimes argue that, without the existence of God, life would be meaningless. Some secular people agree. For instance, in his

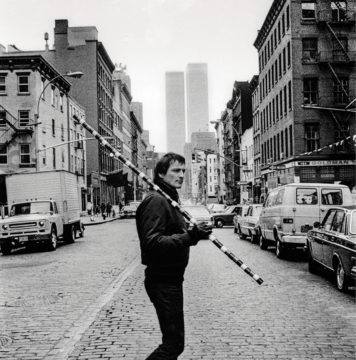

Theologians sometimes argue that, without the existence of God, life would be meaningless. Some secular people agree. For instance, in his  The incompatibility of his enterprise: as he brought one of his homemade object-acts, uninvited, into a gallery or museum opening, gently leaned it against a wall or gently dropped it on the floor, amid the other artists’ works on view, only to be jettisoned, exiled, often, more often than not, artist and stick, abruptly from the proceedings; or purposefully yet leisurely walked with a stick down the street or into a conference; or nestled it in a pastry shop window, something strange and sweet amid the sweets; or let it vogue in Le Grand Chic Parisien, oblique or (even) obtuse to the 1930s fashions, objets, and jewels; tapped it like a kind of herald to conversation in a pub; or slanted it against the fence while guys enjoyed a pickup game of hoops on the other side. He was, wasn’t he, fucking with the contingencies, regimented, rigged, of inside and outside, and of who decides what comes into focus when something uninvited or unacknowledged radiates its difference?

The incompatibility of his enterprise: as he brought one of his homemade object-acts, uninvited, into a gallery or museum opening, gently leaned it against a wall or gently dropped it on the floor, amid the other artists’ works on view, only to be jettisoned, exiled, often, more often than not, artist and stick, abruptly from the proceedings; or purposefully yet leisurely walked with a stick down the street or into a conference; or nestled it in a pastry shop window, something strange and sweet amid the sweets; or let it vogue in Le Grand Chic Parisien, oblique or (even) obtuse to the 1930s fashions, objets, and jewels; tapped it like a kind of herald to conversation in a pub; or slanted it against the fence while guys enjoyed a pickup game of hoops on the other side. He was, wasn’t he, fucking with the contingencies, regimented, rigged, of inside and outside, and of who decides what comes into focus when something uninvited or unacknowledged radiates its difference? Music, Jude Rogers realises towards the end of her perceptive and moving book, The Sound of Being Human, is a “portal”. The term, borrowed from Nina Kraus, an academic who studies the biology of auditory learning, has a scientific meaning: a portal is the part of an organism where things enter and exit, often with transformative effects. Music does that too. “It is a grand, exhilarating entrance to something,” Rogers writes. It allows us to access and express our innermost feelings, and to communicate with others when alternative channels are unavailable.

Music, Jude Rogers realises towards the end of her perceptive and moving book, The Sound of Being Human, is a “portal”. The term, borrowed from Nina Kraus, an academic who studies the biology of auditory learning, has a scientific meaning: a portal is the part of an organism where things enter and exit, often with transformative effects. Music does that too. “It is a grand, exhilarating entrance to something,” Rogers writes. It allows us to access and express our innermost feelings, and to communicate with others when alternative channels are unavailable. Homo sapiens have big brains. We use those brains to develop new technologies, which enable us to produce more stuff and support larger populations on the same amount of land. Higher population density makes possible greater specialization and increases demand for innovation. As a result, cultural attributes that favor education and innovation become more valuable, so families with those attributes are more likely to reproduce, resulting in a population that is more favorable for further technological development.

Homo sapiens have big brains. We use those brains to develop new technologies, which enable us to produce more stuff and support larger populations on the same amount of land. Higher population density makes possible greater specialization and increases demand for innovation. As a result, cultural attributes that favor education and innovation become more valuable, so families with those attributes are more likely to reproduce, resulting in a population that is more favorable for further technological development.