Ben Brubaker in Quanta:

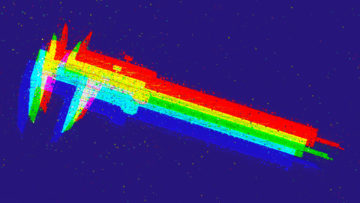

Scientific progress has been inseparable from better measurements.

Scientific progress has been inseparable from better measurements.

Before 1927, only human ingenuity seemed to limit how precisely we could measure things. Then Werner Heisenberg discovered that quantum mechanics imposes a fundamental limit on the precision of some simultaneous measurements. The better you pin down a particle’s position, for instance, the less certain you can possibly be about its momentum. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle put an end to the dream of a perfectly knowable world.

In the 1980s, physicists began to glimpse a silver lining around the cloud of quantum uncertainty. Quantum mechanics, they learned, can be harnessed to aid measurement rather than hinder it — the thesis of a growing discipline known as quantum metrology.

More here.

The idea that committing atrocities and killing innocent victims reflects mental illness has been

The idea that committing atrocities and killing innocent victims reflects mental illness has been  After his grandfather suffered a spinal cord injury in a car accident, Chris Dulla wondered how his wounded brain cells would repair themselves. So when Dulla learned in medical school two decades ago that star-shaped brain cells called astrocytes support neurons and play a vital role in injury response and recovery, he felt the urge to dive deeper into the topic.

After his grandfather suffered a spinal cord injury in a car accident, Chris Dulla wondered how his wounded brain cells would repair themselves. So when Dulla learned in medical school two decades ago that star-shaped brain cells called astrocytes support neurons and play a vital role in injury response and recovery, he felt the urge to dive deeper into the topic. Imagine there were no Beatles—or that there was no Beatlemania anyway and that the lads from Liverpool were just another band that never got a record deal or that split up before they hit it big. That is the premise Harvard University professor

Imagine there were no Beatles—or that there was no Beatlemania anyway and that the lads from Liverpool were just another band that never got a record deal or that split up before they hit it big. That is the premise Harvard University professor  On the back cover of Tariq Ali’s new book on Winston Churchill, a less flattering and so less familiar portrait of the wartime icon comes into view. Here, the man voted the Greatest Briton ever by over a million of his compatriots in 2002 fulminates against everything from women’s suffrage and liberal causes to “international Jews,” “uncivilised tribes” and “people with slit eyes and pigtails.” Ali also alludes to Churchill’s approval of the Conservative slogan “Keep England White”—at the same time MPs like Fenner Brockway were bringing the Race Discrimination Bill to parliament—and includes an extract from the cringeworthy praise he heaped on Mussolini in 1927. Such pronouncements will not be new to anyone familiar with the subject, but to invoke them in rarefied British company is usually to elicit the dismissive claim that they are not representative of Churchill or that they were simply “of their time.” “Nobody’s perfect” goes the more casual response, as if a view of the world in which Anglo-Saxons were “a higher grade race” entitled to rule the rest was simply a charming upper-class foible.

On the back cover of Tariq Ali’s new book on Winston Churchill, a less flattering and so less familiar portrait of the wartime icon comes into view. Here, the man voted the Greatest Briton ever by over a million of his compatriots in 2002 fulminates against everything from women’s suffrage and liberal causes to “international Jews,” “uncivilised tribes” and “people with slit eyes and pigtails.” Ali also alludes to Churchill’s approval of the Conservative slogan “Keep England White”—at the same time MPs like Fenner Brockway were bringing the Race Discrimination Bill to parliament—and includes an extract from the cringeworthy praise he heaped on Mussolini in 1927. Such pronouncements will not be new to anyone familiar with the subject, but to invoke them in rarefied British company is usually to elicit the dismissive claim that they are not representative of Churchill or that they were simply “of their time.” “Nobody’s perfect” goes the more casual response, as if a view of the world in which Anglo-Saxons were “a higher grade race” entitled to rule the rest was simply a charming upper-class foible. “No cancer patient should die without trying immunotherapy” is a refrain in oncology clinics across the country right now. A treatment consisting of antibodies that awaken the immune system to attack cancer, immunotherapy carries far more promise than chemotherapy, and it has considerably fewer side effects. Since the FDA’s first approval a decade ago, it has revolutionized cancer care. Consider Stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Twenty years ago, when the only option was chemotherapy, oncologists could tell their patient, with almost 100 percent certainty, that they would not be alive in two years. Today, miraculously, many patients with Stage IV lung cancer are alive five years after diagnosis — and some are even cured.

“No cancer patient should die without trying immunotherapy” is a refrain in oncology clinics across the country right now. A treatment consisting of antibodies that awaken the immune system to attack cancer, immunotherapy carries far more promise than chemotherapy, and it has considerably fewer side effects. Since the FDA’s first approval a decade ago, it has revolutionized cancer care. Consider Stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Twenty years ago, when the only option was chemotherapy, oncologists could tell their patient, with almost 100 percent certainty, that they would not be alive in two years. Today, miraculously, many patients with Stage IV lung cancer are alive five years after diagnosis — and some are even cured. In recent weeks, I spoke with nearly two dozen people in, adjacent to, and critical of the crypto space about what they envision to be the purpose of crypto. What emerged was a picture that was simultaneously murky and clarifying, in that there’s not one good answer. Some of what it does is promising; a lot of what it does — even boosters admit — is trash, and trash that’s costing some people a lot of money. This probably isn’t the death knell for crypto — it’s gone through plenty of boom and bust cycles in the past. It would be unwise to definitively say that crypto has no chance of being a game changer; it would also be disingenuous to claim it is now.

In recent weeks, I spoke with nearly two dozen people in, adjacent to, and critical of the crypto space about what they envision to be the purpose of crypto. What emerged was a picture that was simultaneously murky and clarifying, in that there’s not one good answer. Some of what it does is promising; a lot of what it does — even boosters admit — is trash, and trash that’s costing some people a lot of money. This probably isn’t the death knell for crypto — it’s gone through plenty of boom and bust cycles in the past. It would be unwise to definitively say that crypto has no chance of being a game changer; it would also be disingenuous to claim it is now. For a number of weeks one spring, I spent every afternoon at the Basilica di San Francesco d’Assisi. It was what we then thought was the tail end of a plague, and I had come to Italy to visit a friend who had lived for many years a few kilometers above Assisi, in an old schoolhouse. This turned out not to be the visit I had imagined, nor, I am sure, the one she had, and after a few weeks, I went to Rome. But before that, every afternoon, I drove down into town—I had rented a car—past the long flank of Monte Subasio, with its temperate oxen, parked on the escarpment before the gates because the switchback of tiny streets flummoxed me, and walked down to the basilica. Everything was off-kilter, as if a great wave had passed over us, and now, if we were lucky to be alive, we found ourselves stranded on the banks of our own lives or paddling furiously toward where we imagined the shore might be. I had been to the basilica and to Assisi many times over the years to visit my friend, and so I knew my way on the small strade that opened and closed into a series of piazze, as if the town had exhaled and then drawn breath again.

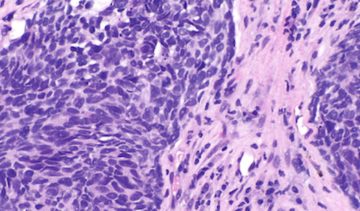

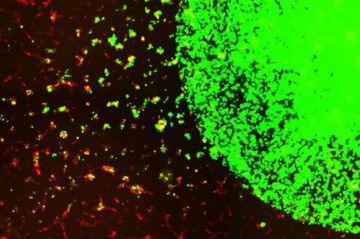

For a number of weeks one spring, I spent every afternoon at the Basilica di San Francesco d’Assisi. It was what we then thought was the tail end of a plague, and I had come to Italy to visit a friend who had lived for many years a few kilometers above Assisi, in an old schoolhouse. This turned out not to be the visit I had imagined, nor, I am sure, the one she had, and after a few weeks, I went to Rome. But before that, every afternoon, I drove down into town—I had rented a car—past the long flank of Monte Subasio, with its temperate oxen, parked on the escarpment before the gates because the switchback of tiny streets flummoxed me, and walked down to the basilica. Everything was off-kilter, as if a great wave had passed over us, and now, if we were lucky to be alive, we found ourselves stranded on the banks of our own lives or paddling furiously toward where we imagined the shore might be. I had been to the basilica and to Assisi many times over the years to visit my friend, and so I knew my way on the small strade that opened and closed into a series of piazze, as if the town had exhaled and then drawn breath again. Glioblastomas (GBMs) are highly aggressive cancerous tumors of the brain and spinal cord. Brain cancers like GBM are challenging to treat because many cancer therapeutics cannot pass through the blood-brain barrier, and more than 90 percent of GBM tumors return after being surgically removed, despite surgery and subsequent chemo- and radiation therapy being the most successful way to treat the disease. In a new study led by investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, scientists devised a novel therapeutic strategy for treating GBMs post-surgery by using stem cells taken from healthy donors engineered to attack GBM-specific tumor cells. This strategy demonstrated profound efficacy in preclinical models of GBM, with 100 percent of mice living over 90 days after treatment.

Glioblastomas (GBMs) are highly aggressive cancerous tumors of the brain and spinal cord. Brain cancers like GBM are challenging to treat because many cancer therapeutics cannot pass through the blood-brain barrier, and more than 90 percent of GBM tumors return after being surgically removed, despite surgery and subsequent chemo- and radiation therapy being the most successful way to treat the disease. In a new study led by investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, scientists devised a novel therapeutic strategy for treating GBMs post-surgery by using stem cells taken from healthy donors engineered to attack GBM-specific tumor cells. This strategy demonstrated profound efficacy in preclinical models of GBM, with 100 percent of mice living over 90 days after treatment. Is moral expertise possible? Well, we certainly act like it is in our everyday judgments of other people. We judge some people as lacking moral expertise, insofar as we don’t expect very good moral decision-making from them, we don’t seek out their advice on moral issues, and we don’t praise them as moral role models. Such people include young children, low-IQ adults, older adults with dementia, and criminal psychopaths.

Is moral expertise possible? Well, we certainly act like it is in our everyday judgments of other people. We judge some people as lacking moral expertise, insofar as we don’t expect very good moral decision-making from them, we don’t seek out their advice on moral issues, and we don’t praise them as moral role models. Such people include young children, low-IQ adults, older adults with dementia, and criminal psychopaths. Spillover events, in which a pathogen that originates in animals jumps into people, have probably triggered every viral pandemic that’s occurred since the start of the twentieth century

Spillover events, in which a pathogen that originates in animals jumps into people, have probably triggered every viral pandemic that’s occurred since the start of the twentieth century Ta-Nehisi Coates is best known for his writing about racism in America—in particular, his 2014 essay “The Case for Reparations,” and his 2015 book, Between the World and Me. Ta-Nehisi’s readers know that the toll racism has inflicted on the bodies of Black people, and the enduring power of white supremacy, have long preoccupied him. On this show, however, he’ll be talking about a subject—or rather an influence—that few people associate with his work.

Ta-Nehisi Coates is best known for his writing about racism in America—in particular, his 2014 essay “The Case for Reparations,” and his 2015 book, Between the World and Me. Ta-Nehisi’s readers know that the toll racism has inflicted on the bodies of Black people, and the enduring power of white supremacy, have long preoccupied him. On this show, however, he’ll be talking about a subject—or rather an influence—that few people associate with his work.