Category: Recommended Reading

Wednesday Poem

Azza and I Share a Cup of Tea

We find a perfect piece of shade underneath the warm sun,

and Azza pours the tea before she speaks

Azza never looks the same.

Each time you get close enough, each time you think you know her,

she reveals another surface

If you don’t pay attention, you might almost miss it

the way her crisp white toub falls gracefully on her shoulders,

how the gold crescent in her nose accentuates her face tenderly

Azza is timid, but captures your attention

She is not a mere stop on your destination

So, plan to stay awhile.

Listen to the way she uses language to weave stories full of heart

Pay attention to how she sings songs of love

Count the scars and ask her how many battles she has fought

You will be surprised to learn how many of them she’s won.

Sip your tea slowly and know that she will offer you a place to stay

Let her soft voice trickle into your ears, and

Let the cool breeze touch your skin

Global warming will make record-breaking temperatures in India and Pakistan much more frequent

Jude Coleman in Nature:

Human-induced climate change made the deadly heatwave that gripped India and Pakistan in March and April 30 times more likely, according to a rapid analysis of the event. Temperatures began rising earlier than usual in March, shattering records and claiming at least 90 lives. The prolonged heat has yet to subside. “High temperatures are common in India and Pakistan, but what made this unusual was that it started so early and lasted so long,” said co-author Krishna AchutaRao, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Technology in New Delhi, in a press release. “We know this will happen more often as temperatures rise and we need to be better prepared for it,” AchutaRao said.

Human-induced climate change made the deadly heatwave that gripped India and Pakistan in March and April 30 times more likely, according to a rapid analysis of the event. Temperatures began rising earlier than usual in March, shattering records and claiming at least 90 lives. The prolonged heat has yet to subside. “High temperatures are common in India and Pakistan, but what made this unusual was that it started so early and lasted so long,” said co-author Krishna AchutaRao, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Technology in New Delhi, in a press release. “We know this will happen more often as temperatures rise and we need to be better prepared for it,” AchutaRao said.

To quantify the role of climate change in the extreme heatwave, a global team of researchers from the World Weather Attribution (WWA) initiative used the average daily maximum temperatures across northwestern India and southeastern Pakistan between March and April to characterize the heatwave. They then compared the possibility of such an event occurring in today’s climate compared with the climate in pre-industrial times, using a combination of climate models and observation data going back to 1979 in Pakistan and 1951 in India.

The team found that climate change increased the probability of the heatwave occurring to once in every 100 years; the odds of such an event would have been once every 3,000 years in pre-industrial times, says Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist and researcher at Berkeley Earth, a non-profit organization in California that focuses on climate change and analysis of global temperatures. The researchers also show that the event was around 1 ºC warmer than it would have been in a pre-industrial climate.

More here.

The ‘straight, white, Christian, suburban mom’ taking on Republicans at their own game

David Smith in The Guardian:

Mallory McMorrow remembers the sting of being slandered by a colleague for wanting to “groom” and “sexualize” young children. “I felt horrible,” she says. But instead of shrugging it off or trying to change the subject, as Democrats are often criticised for doing, the state senator from Michigan decided to fight back. In just four minutes and 40 seconds, McMorrow delivered a fierce, impassioned floor speech at the state capitol that went viral on social media and earned a laudatory phone call from the US president. She also offered a blueprint for how Democrats can combat Republicans intent on making education a wedge issue. The New Yorker magazine described her as “a role model for the midterms”. The New York Times newspaper added: “If Democrats could bottle Mallory McMorrow … they would do it.”

Mallory McMorrow remembers the sting of being slandered by a colleague for wanting to “groom” and “sexualize” young children. “I felt horrible,” she says. But instead of shrugging it off or trying to change the subject, as Democrats are often criticised for doing, the state senator from Michigan decided to fight back. In just four minutes and 40 seconds, McMorrow delivered a fierce, impassioned floor speech at the state capitol that went viral on social media and earned a laudatory phone call from the US president. She also offered a blueprint for how Democrats can combat Republicans intent on making education a wedge issue. The New Yorker magazine described her as “a role model for the midterms”. The New York Times newspaper added: “If Democrats could bottle Mallory McMorrow … they would do it.”

…Why did the speech strike such a chord? McMorrow suggests that Democrats have been afraid of talking about religion and faith openly while Republicans have sought to weaponise Christianity and create the illusion that they speak on behalf of all white suburban mothers. She reflects: “It feels like Democrats have ceded ground to the Republican party on Christianity and religion and family values and patriotism. Waving a lot of American flags tends to be associated with the Republican party now despite the fact that many of my colleagues supported the insurrection [in Washington on January 6, 2021].

More here.

Tuesday, May 24, 2022

The Fiction That Dare Not Speak Its Name

Morten Høi Jensen in Liberties:

Pity literary biographers. There are few writers less appreciated, there are none more despised. There they sit, with their church bulletins of family trees and their dental records, their interviews with ex-lovers, mad uncles, and discarded children, and go about “reconstructing” the life of someone they never knew, or knew just barely. To George Eliot, biographers were a “disease of English literature,” while Auden thought all literary biographies “superfluous and usually in bad taste.” Even Ian Hamilton, the intrepid chronicler of Robert Lowell, J. D. Salinger, and Matthew Arnold, thought that there was “some necessary element of sleaze” to the whole enterprise.

Pity literary biographers. There are few writers less appreciated, there are none more despised. There they sit, with their church bulletins of family trees and their dental records, their interviews with ex-lovers, mad uncles, and discarded children, and go about “reconstructing” the life of someone they never knew, or knew just barely. To George Eliot, biographers were a “disease of English literature,” while Auden thought all literary biographies “superfluous and usually in bad taste.” Even Ian Hamilton, the intrepid chronicler of Robert Lowell, J. D. Salinger, and Matthew Arnold, thought that there was “some necessary element of sleaze” to the whole enterprise.

And yet biographies of writers continue to excite the reading public’s imagination. Last year alone saw big new accounts of the lives of W. G. Sebald, Fernando Pessoa, Philip Roth, Tom Stoppard, D. H. Lawrence, Elizabeth Hardwick, H.G. Wells, Stephen Crane, and Sylvia Plath. The most controversial of these, of course, was Blake Bailey’s biography of Roth, which was withdrawn by its publisher just a few weeks after it appeared owing to accusations against Bailey of sexual assault and inappropriate behavior.

More here.

How Australia Saved Thousands of Lives While Covid Killed a Million Americans

Damien Cave in the New York Times:

Both countries are English-speaking democracies with similar demographic profiles. In Australia and in the United States, the median age is 38. Roughly 86 percent of Australians live in urban areas, compared with 83 percent of Americans.

Both countries are English-speaking democracies with similar demographic profiles. In Australia and in the United States, the median age is 38. Roughly 86 percent of Australians live in urban areas, compared with 83 percent of Americans.

Yet Australia’s Covid death rate sits at one-tenth of America’s, putting the nation of 25 million people (with around 7,500 deaths) near the top of global rankings in the protection of life.

Australia’s location in the distant Pacific is often cited as the cause for its relative Covid success. That, however, does not fully explain the difference in outcomes between the two countries, since Australia has long been, like the United States, highly connected to the world through trade, tourism and immigration. In 2019, 9.5 million international tourists came to Australia. Sydney and Melbourne could just as easily have become as overrun with Covid as New York or any other American city.

More here.

The history of the British Empire’s violence

Howard W. French in The Nation:

In 2005, Britain’s then–Labour chancellor of the exchequer, Gordon Brown, chose the backdrop of Tanzania to make a dramatic statement about his nation’s unmatched record of imperial conquest and rule. “The time is long gone,” he said, “when Britain needs to apologize for its colonial history.” The choice of locale for such a proclamation was, to be charitable, curious. A braver stage would have been Kenya, to pick an African nation that had experienced horrific violence during its independence struggle from British colonial rule, or India or Malaya, where extreme and brutal measures to sustain imperial control had been carried out on an even greater scale. But here we were, nonetheless.

In 2005, Britain’s then–Labour chancellor of the exchequer, Gordon Brown, chose the backdrop of Tanzania to make a dramatic statement about his nation’s unmatched record of imperial conquest and rule. “The time is long gone,” he said, “when Britain needs to apologize for its colonial history.” The choice of locale for such a proclamation was, to be charitable, curious. A braver stage would have been Kenya, to pick an African nation that had experienced horrific violence during its independence struggle from British colonial rule, or India or Malaya, where extreme and brutal measures to sustain imperial control had been carried out on an even greater scale. But here we were, nonetheless.

Brown’s speech reflected the slow and creaky rotation of the wheel not so much of history but of historiography. Mirroring 19th-century historians’ and politicians’ polished encomiums to a beneficent British Empire, the speech brought elite assessments of Britain’s unparalleled dominion over one quarter of the globe, and over a similar fraction of the human population, almost full circle.

More here.

How does the brain retrieve memories, articulate words, and focus attention?

Is Anna Wintour human?

Lynn Barber in The Spectator:

Apparently Anna Wintour wants to be seen as human, and Amy Odell’s biography goes some way to helping her achieve that aim. Nearly all the photographs show her smiling, looking friendly, even girlish. And the text quite often mentions her crying. On 9 November 2016 she cried in front of her entire staff because Hillary Clinton lost the election. But then she immediately set about trying to persuade Melania Trump to do a Vogue shoot. Melania, another tough cookie, refused unless she was guaranteed the cover.

Apparently Anna Wintour wants to be seen as human, and Amy Odell’s biography goes some way to helping her achieve that aim. Nearly all the photographs show her smiling, looking friendly, even girlish. And the text quite often mentions her crying. On 9 November 2016 she cried in front of her entire staff because Hillary Clinton lost the election. But then she immediately set about trying to persuade Melania Trump to do a Vogue shoot. Melania, another tough cookie, refused unless she was guaranteed the cover.

Dame Anna has been the editor of American Vogue since 1988 and holds a position of extraordinary power in the fashion world. Designers, photographers, models and celebs tremble to obey her whim. At 72, she now seems impregnable, in that she is the creative director of all Condé Nast magazines, from Vogue down to Golf Digest and Wired. But of course this is a print empire, which means she could be the last empress.

We know Wintour best from The Devil Wears Prada, the 2006 film based on a novel by her former assistant Lauren Weisberger. Everything in Odell’s biography confirms its accuracy – the relentless perfectionism, the exhausting work routine, up at 5 a.m., tennis or workout, followed by half an hour of hair and makeup before entering the office, where assistants wait to hand her coffee, then a day of back-to-back meetings. Everything is work. She doesn’t believe in wasting time, so no small talk, no pleasantries, no explanations. And she will get up from lunch after 45 minutes, whether or not her guests are still eating.

More here.

Climate change could lead to a net expansion of global forests. But will a more forested world actually be cooler?

Fred Pearce in Science:

These are strange times for the Indigenous Nenets reindeer herders of northern Siberia. In their lands on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, bare tundra is thawing, bushes are sprouting, and willows that a generation ago struggled to reach knee height now grow 3 meters tall, hiding the reindeer. Surveys show the Nenets autonomous district, an area the size of Florida, now has four times as many trees as official inventories recorded in the 1980s. In some places the trees are advancing along a wide front, but in other places the gains are patchier, says forest ecologist Dmitry Schepaschenko of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria, who has mapped the greening of the Siberian tundra. “A few trees appear here and there, and some shrublike trees become higher.”

These are strange times for the Indigenous Nenets reindeer herders of northern Siberia. In their lands on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, bare tundra is thawing, bushes are sprouting, and willows that a generation ago struggled to reach knee height now grow 3 meters tall, hiding the reindeer. Surveys show the Nenets autonomous district, an area the size of Florida, now has four times as many trees as official inventories recorded in the 1980s. In some places the trees are advancing along a wide front, but in other places the gains are patchier, says forest ecologist Dmitry Schepaschenko of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria, who has mapped the greening of the Siberian tundra. “A few trees appear here and there, and some shrublike trees become higher.”

All around the Arctic Circle, trees are invading as the climate warms. In Norway, birch and pine are marching poleward, eclipsing the tundra. In Alaska, spruce are taking over from moss and lichen. Globally, recent research indicates forests are expanding along two-thirds of Earth’s 12,000-kilometer-long northern tree line—the point where forests give way to tundra—while receding along just 1% (see map, below).

More here.

Will Rogers in John Ford’s America

Adam Piron at Current:

There is a scene in Fox’s 1930 comedy So This Is London in which Hiram Draper, played by Will Rogers, attempts to get a passport. When Hiram is unable to provide a birth certificate, the passport-office official inquires if he is an American citizen. Rogers, in his thick Oklahoman accent, responds: “I think I am. My folks are Indian. Both my mother and father had Cherokee blood in ’em. Born and raised in Indian Territory. Of course, I’m not one of these Americans whose ancestors come over on the Mayflower, but we met ’em when they landed.” It’s a great bit of comedy, a pre-Code jab pointing out an existential absurdity of America itself. It’s also a key to Rogers’s brand of humor and his positioning as a straight-talking outsider lodged in the eye of popular culture’s storm.

There is a scene in Fox’s 1930 comedy So This Is London in which Hiram Draper, played by Will Rogers, attempts to get a passport. When Hiram is unable to provide a birth certificate, the passport-office official inquires if he is an American citizen. Rogers, in his thick Oklahoman accent, responds: “I think I am. My folks are Indian. Both my mother and father had Cherokee blood in ’em. Born and raised in Indian Territory. Of course, I’m not one of these Americans whose ancestors come over on the Mayflower, but we met ’em when they landed.” It’s a great bit of comedy, a pre-Code jab pointing out an existential absurdity of America itself. It’s also a key to Rogers’s brand of humor and his positioning as a straight-talking outsider lodged in the eye of popular culture’s storm.

Like Hiram Draper, Rogers was a citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. He was born in 1879, raised in a prominent family within his tribe’s territory, and was the grandchild of survivors of the Trail of Tears. By his own account, Rogers was a poor student and found himself drawn to Cherokee ranching culture.

more here.

Will Rogers – Bacon, Beans, and Limousines

The Irreconcilable Fanny Howe

Jamie Hood at The Baffler:

Howe’s latest book, London-rose: Beauty Will Save the World, is a strange, changeable artifact. As does much of her work, it luxuriates in formal and generic plasticity: it is not poetry, exactly, but nor is it precisely prose. London-rose might be more usefully regarded as a consortium of fragments—historical apocrypha, lists, philosophic and monastic citations, and other ephemera—which are loosely gathered in the folds of a skeletal plot concerning an unnamed and structurally anonymized female pencil pusher. Howe called 2020’s Night Philosophy her “last” book, and to give credit where it is due, London-rose isn’t technically “new.” The manuscript is traceable in some form to the early 1990s, the decade during which Howe was in the thick of a sequence of five novels she has said are as near to a personal biography as she wishes to get. (They were collected in an omnibus as Radical Love by Nightboat in 2006, and the last of them—Indivisible—is being reissued in tandem with the publication of London-rose.)

Howe’s latest book, London-rose: Beauty Will Save the World, is a strange, changeable artifact. As does much of her work, it luxuriates in formal and generic plasticity: it is not poetry, exactly, but nor is it precisely prose. London-rose might be more usefully regarded as a consortium of fragments—historical apocrypha, lists, philosophic and monastic citations, and other ephemera—which are loosely gathered in the folds of a skeletal plot concerning an unnamed and structurally anonymized female pencil pusher. Howe called 2020’s Night Philosophy her “last” book, and to give credit where it is due, London-rose isn’t technically “new.” The manuscript is traceable in some form to the early 1990s, the decade during which Howe was in the thick of a sequence of five novels she has said are as near to a personal biography as she wishes to get. (They were collected in an omnibus as Radical Love by Nightboat in 2006, and the last of them—Indivisible—is being reissued in tandem with the publication of London-rose.)

more here.

Tuesday Poem

In All This Rain

—for Doktor Bruder,

the dachshund

Despite

what is written

about the rain

love is one element

that takes more sense

than any other

to know when

to come in out of.

It rains

sooner or later of course on

everything we bury

And burying a dog

is not

according to experts

supposed to be anything like

as painful

as burying your kin.

They say

think of it as sleep

in which the stars also

all go out at once

the stars that you know

are still up there

but just can’t see.

Sunday, May 22, 2022

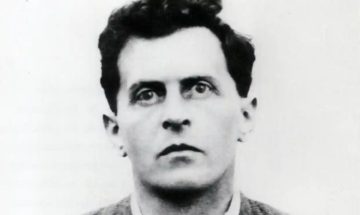

Private Notebooks 1914-1916 by Ludwig Wittgenstein – sex and logic

Anil Gomes in The Guardian:

Ludwig Wittgenstein joined the army the day after his native Austria-Hungary declared war on Russia in August 1914. He had been serving for almost three months when he received word that his brother Paul, a concert pianist, had lost his right arm in battle. “Again and again,” he wrote in his notebook, “I have to think of poor Paul, who has so suddenly been deprived of his vocation! How terrible! What philosophical outlook would it take to overcome such a thing? Can it even happen except through suicide!”

Ludwig Wittgenstein joined the army the day after his native Austria-Hungary declared war on Russia in August 1914. He had been serving for almost three months when he received word that his brother Paul, a concert pianist, had lost his right arm in battle. “Again and again,” he wrote in his notebook, “I have to think of poor Paul, who has so suddenly been deprived of his vocation! How terrible! What philosophical outlook would it take to overcome such a thing? Can it even happen except through suicide!”

Wittgenstein was an unusual philosopher. He became obsessed with the foundations of logic while an engineering student and presented himself to Bertrand Russell in Cambridge, ready to solve all its problems. His intent was to provide an account of logic that was free from paradox and his solution came in the form of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, sent to Russell from the Italian prisoner-of-war camp in which Wittgenstein was held at the end of the first world war.

More here.

Lavender’s Game: Silexan For Anxiety

Scott Alexander in Astral Codex Ten:

There are dozens of natural supplements that purport to treat anxiety. Most have a few small sketchy studies backing them up. Together, they form a big amorphous mass of claims that nobody has the patience to sift through or care about.

There are dozens of natural supplements that purport to treat anxiety. Most have a few small sketchy studies backing them up. Together, they form a big amorphous mass of claims that nobody has the patience to sift through or care about.

But recently silexan (derived from lavender) has started to stand out of the crowd. Daily Mail had an interview with psychiatry professor Hans-Peter Volz, who said that silexan should be first-line for anxiety, replacing things like SSRIs and Xanax. And a very reputable professional publication within psychiatry, The Carlat Report, published an article and a podcast touting silexan:

Not many treatments in psychiatry have a large effect size. There’s stimulants for ADHD, ketamine for depression . . . and now Silexan for generalized anxiety disorder.

And:

Most [alternative medicine] therapies do not have robust effects, but Silexan is an exception. Consider it in adults with generalized anxiety disorder.

What’s going on?

More here.

Nabokov and Balthus: The Erotic Imagination

Jeffrey Meyers in Salmagundi:

Despite their idiosyncratic characters, the close contemporaries Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977) and Balthazar (Balthus) Klossowski (1908-2001) had a surprisingly similar background, life, character, art and career. In fact, both author and painter were exceptionally handsome, with elegant manners and regal demeanor, and had sophisticated wit, comic irony, perverse ideas and lubricious work.

Nabokov was born in St. Petersburg. His father, who belonged to the Russian nobility, was a Liberal lawyer, statesman and writer, and a member of Alexander Kerensky’s doomed cabinet in March 1917. In the days before the Revolution the wealthy family took many holidays in Europe, and had fifty full-time servants in their St. Petersburg mansion and their country estate fifty miles from the capital.

Balthus also had a cosmopolitan Slavic background. His maternal grandfather Abraham Spiro, born in Russia, was a Jewish cantor and two of his thirteen children became opera singers. (Nabokov’s wife was Jewish and his son Dmitri became an opera singer in Milan.)

More here.

To End War, We Need To Understand Its Origins, Evolution And Causes

Michael L. Wilson and Richard W. Wrangham in Monkey Business:

In a recent opinion piece for Scientific American, John Horgan writes “Ending war won’t be easy, but it should be a moral imperative, as much so as ending slavery and the subjugation of women. The first step toward ending war is believing it is possible.” As part of his argument he declared that “far from having deep evolutionary roots, [war] is a relatively recent cultural invention.” We cherish the goal of ending war, but regard the claim of war being independent of our evolutionary past as unjustified, irresponsible and improbable. It is possibly based on a misunderstanding of what it means for a behavior to have evolutionary roots, but regardless of its derivation, we see it as dangerous. The problem is that if Horgan’s view prevails, we close our minds to potentially important contributions towards understanding the causes of wars.

More here.

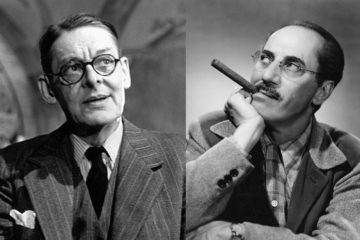

All Male Cats Are Named Tom: Or, the Uneasy Symbiosis between T. S. Eliot and Groucho Marx

Ed Simon in JSTOR Daily:

In 1961 a letter with a Royal Mail postmark arrived at 1083 North Hillcrest Road, Beverly Hills. Fan mail sent to this modernist estate amidst the California scrub were not uncommon. After all, it was the home of Julius “Groucho” Marx, the visionary leader of the fraternal comedic group. This particular note had a return address of 3 Kensington Court Gardens, a continent and an ocean away.

In 1961 a letter with a Royal Mail postmark arrived at 1083 North Hillcrest Road, Beverly Hills. Fan mail sent to this modernist estate amidst the California scrub were not uncommon. After all, it was the home of Julius “Groucho” Marx, the visionary leader of the fraternal comedic group. This particular note had a return address of 3 Kensington Court Gardens, a continent and an ocean away.

Groucho Marx had no shortage of fans, as the Marx Brothers revolutionized American comedy in films such as Duck Soup, A Night at the Opera, and, notably, Horse Feathers, in which Groucho plays a college dean, with the mockingly patrician name Quincy Adams Wagstaff. Overseeing an assemblage of pompous, mortar-boarded, gown-wearing academics who dance and sing, Wagstaff says “I don’t know what they have to say/It makes no difference anyway.” It’s an “anarchic expression of distrust of any form of social or political organization,” according to Leonard Helfgott in an essay from Jews and Humor, and shows exactly how the Brothers went about their business of puncturing pretension.

More here.

Mindfulness Hurts. That’s Why It Works

Arthur C. Brooks in The Atlantic:

Some years ago, a friend told me that his marriage was suffering because he was on the road so much for work. I started counseling him on how to fix things—to move more meetings online, to make do with less money. But no matter what I suggested, he always had a counterargument for why it was impossible. Finally, it dawned on me: His issue wasn’t a logistics or work-management problem. It was a home problem. As he ultimately acknowledged, he didn’t like being there, but he was unwilling to confront the real source of his troubles.

Some years ago, a friend told me that his marriage was suffering because he was on the road so much for work. I started counseling him on how to fix things—to move more meetings online, to make do with less money. But no matter what I suggested, he always had a counterargument for why it was impossible. Finally, it dawned on me: His issue wasn’t a logistics or work-management problem. It was a home problem. As he ultimately acknowledged, he didn’t like being there, but he was unwilling to confront the real source of his troubles.

Many of us, even if we don’t travel for work, do something similar by avoiding spending time in the home of our own mind. If being fully present—or in the parlance of modern meditators, being mindful—is boring, or stressful, or sad, or scary, you’re not going to want to do it very much. You can have a more pleasant time being psychologically out of town, as it were.

But you should work to be more mindful anyway. As I told my friend, he’d be better off facing the problems in his marriage and trying to solve them, rather than living in a hotel off the interstate five days a week. Similarly, avoiding mindfulness will make the feelings you are avoiding worse, not better. Dealing with them is a more rewarding, if perhaps more daunting, strategy.

More here.