Arthur C. Brooks in The Atlantic:

Some years ago, a friend told me that his marriage was suffering because he was on the road so much for work. I started counseling him on how to fix things—to move more meetings online, to make do with less money. But no matter what I suggested, he always had a counterargument for why it was impossible. Finally, it dawned on me: His issue wasn’t a logistics or work-management problem. It was a home problem. As he ultimately acknowledged, he didn’t like being there, but he was unwilling to confront the real source of his troubles.

Some years ago, a friend told me that his marriage was suffering because he was on the road so much for work. I started counseling him on how to fix things—to move more meetings online, to make do with less money. But no matter what I suggested, he always had a counterargument for why it was impossible. Finally, it dawned on me: His issue wasn’t a logistics or work-management problem. It was a home problem. As he ultimately acknowledged, he didn’t like being there, but he was unwilling to confront the real source of his troubles.

Many of us, even if we don’t travel for work, do something similar by avoiding spending time in the home of our own mind. If being fully present—or in the parlance of modern meditators, being mindful—is boring, or stressful, or sad, or scary, you’re not going to want to do it very much. You can have a more pleasant time being psychologically out of town, as it were.

But you should work to be more mindful anyway. As I told my friend, he’d be better off facing the problems in his marriage and trying to solve them, rather than living in a hotel off the interstate five days a week. Similarly, avoiding mindfulness will make the feelings you are avoiding worse, not better. Dealing with them is a more rewarding, if perhaps more daunting, strategy.

More here.

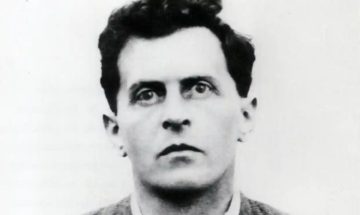

Ludwig Wittgenstein joined the army the day after his native Austria-Hungary declared war on Russia in August 1914. He had been serving for almost three months when he received word that his brother Paul, a concert pianist, had lost his right arm in battle. “Again and again,” he wrote in his notebook, “I have to think of poor Paul, who has so suddenly been deprived of his vocation! How terrible! What philosophical outlook would it take to overcome such a thing? Can it even happen except through suicide!”

Ludwig Wittgenstein joined the army the day after his native Austria-Hungary declared war on Russia in August 1914. He had been serving for almost three months when he received word that his brother Paul, a concert pianist, had lost his right arm in battle. “Again and again,” he wrote in his notebook, “I have to think of poor Paul, who has so suddenly been deprived of his vocation! How terrible! What philosophical outlook would it take to overcome such a thing? Can it even happen except through suicide!” There are dozens of natural supplements that purport to treat anxiety. Most have a few small sketchy studies backing them up. Together, they form a big amorphous mass of claims that nobody has the patience to sift through or care about.

There are dozens of natural supplements that purport to treat anxiety. Most have a few small sketchy studies backing them up. Together, they form a big amorphous mass of claims that nobody has the patience to sift through or care about.

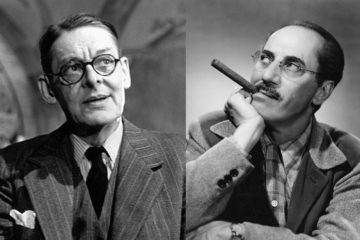

In 1961 a letter with a Royal Mail postmark arrived at 1083 North Hillcrest Road, Beverly Hills. Fan mail sent to this modernist estate amidst the California scrub were not uncommon. After all, it was the home of Julius “Groucho” Marx, the visionary leader of the fraternal comedic group. This particular note had a return address of 3 Kensington Court Gardens, a continent and an ocean away.

In 1961 a letter with a Royal Mail postmark arrived at 1083 North Hillcrest Road, Beverly Hills. Fan mail sent to this modernist estate amidst the California scrub were not uncommon. After all, it was the home of Julius “Groucho” Marx, the visionary leader of the fraternal comedic group. This particular note had a return address of 3 Kensington Court Gardens, a continent and an ocean away. S

S Andrew Yamakawa Elrod in Phenomenal World:

Andrew Yamakawa Elrod in Phenomenal World: I’m not at the Cannes Film Festival, but a few days ago the festival came to me, at a New York screening of a movie that premièred today at Cannes. The film is

I’m not at the Cannes Film Festival, but a few days ago the festival came to me, at a New York screening of a movie that premièred today at Cannes. The film is  Last fall, I made my first visit to London since the start of the pandemic. A routine commuter flight from Europe felt like a great adventure, and once I’d jumped through the bureaucratic hoops, I was excited to arrive. But the city looked disappointingly unchanged after everything the world had gone through. The only thing that really shocked me was something I hadn’t expected: hearing people speaking English. After two years away from it, I had never felt so moved to encounter my own language.

Last fall, I made my first visit to London since the start of the pandemic. A routine commuter flight from Europe felt like a great adventure, and once I’d jumped through the bureaucratic hoops, I was excited to arrive. But the city looked disappointingly unchanged after everything the world had gone through. The only thing that really shocked me was something I hadn’t expected: hearing people speaking English. After two years away from it, I had never felt so moved to encounter my own language. It was if he’d stepped, steaming, out of a Tom of Finland drawing. “My definition of tit for tat,” he wrote, is: “You lick my tattoo while I handle your nipple.”

It was if he’d stepped, steaming, out of a Tom of Finland drawing. “My definition of tit for tat,” he wrote, is: “You lick my tattoo while I handle your nipple.” A

A  From the Dynomight blog:

From the Dynomight blog: